PART 1 | PART 2

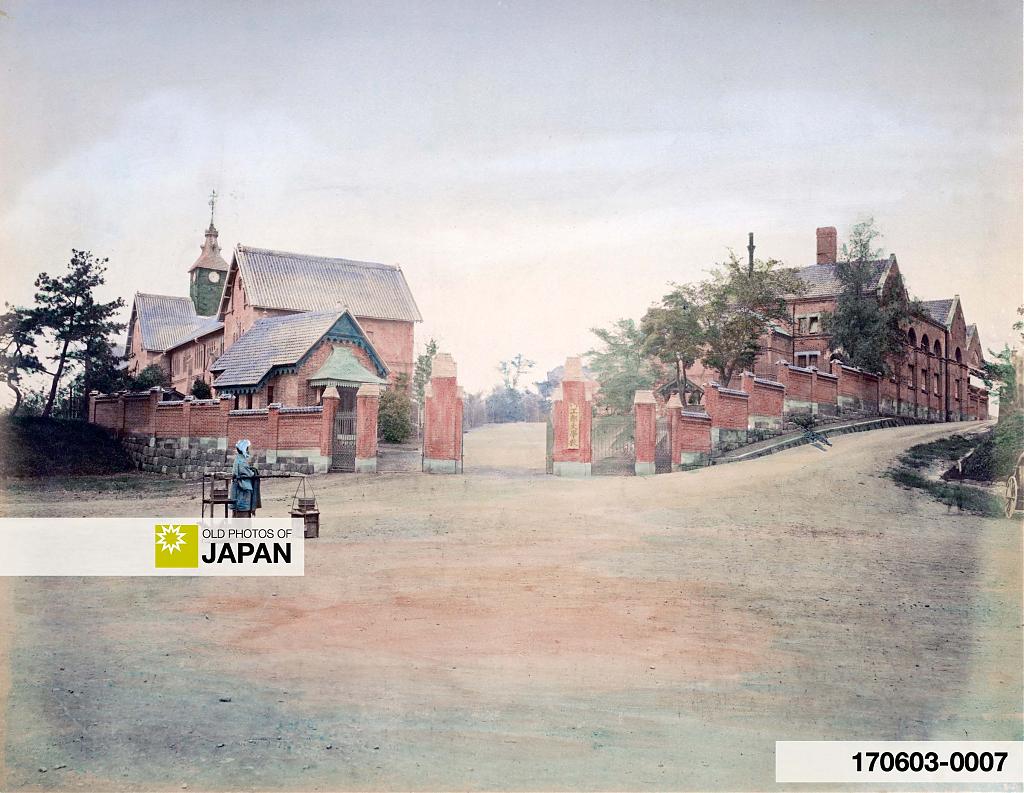

This unassuming factory in Osaka, owned by the Dai-Nippon Artificial Fertilizer Company, tells the little-known story of Japan’s green revolution. By the 1930s, Japan had doubled the output of six major staples and ranked fifth globally in per-acre fertilizer consumption.

This site is funded by readers like you

Old Photos of Japan provides thoroughly researched essays and rare images of daily life in old Japan free of charge and advertising. Most images have been acquired, scanned, and conserved to protect them for future generations.

I rely on readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support this work.

The Dai-Nippon Artificial Fertilizer Company was founded in 1887 (Meiji 20) by two remarkable men who left lasting marks on history. One I introduced before: Eiichi Shibusawa (渋沢栄一, 1840–1931), the visionary industrialist known as the “father of Japanese capitalism.” The other was Jōkichi Takamine (高峰譲吉, 1854–1922), a pioneering chemist. His discovery of synthetic adrenaline, also known as epinephrine, helped establish the biotechnology industry in the United States.1

Takamine is fascinating. Born into a provincial samurai family in what is today Toyama Prefecture, he learned English in Nagasaki from the influential Dutch missionary Guido Verbeck. He later married American socialite Caroline Fields Hitch (1866–1954), emigrated to the United States, and became a millionaire.

When Shibusawa and Takamine founded Dai-Nippon, chemistry was a brand new field in Japan. It was only eight years since Takamine had graduated, as one of Japan’s first university graduates, from the prestigious Imperial College of Engineering (工部大学校, Kōbu Daigakkō), later absorbed by the University of Tokyo.2

After Takamine’s graduation, Japan’s Ministry of Engineering selected him as one of eleven students to study in Great Britain. There he studied industrial chemistry, including artificial fertilizer production. Upon his return to Japan, he joined the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, where he did research on improving Japan’s traditional industries with modern science and technology.

In 1884 (Meiji 17), Takamine visited the World Cotton Centennial in New Orleans and became fascinated by phosphatic fertilizer, at the time a fairly new product in the United States. Takamine saw it as a crucial step forward from Japan’s age-old organic methods.3 Soon after, he reached out to Shibusawa to build Asia’s first production plant for superphosphate.4

Dai-Nippon became extraordinary successful. Now known as Nissan Chemical Corporation, it is a leading company in Japan’s chemicals industry. When the top photo was taken in 1913 (Taishō 2), Dai-Nippon already operated eight factories across Japan, including three in Osaka.5

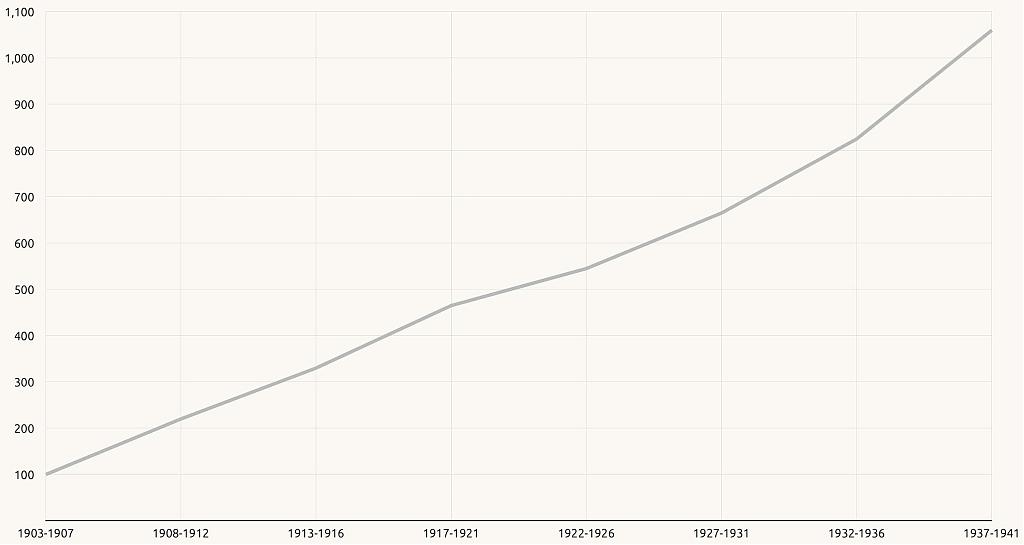

The company was a major force behind Japanese farmers’ staggering increase in the use of commercial fertilizers. Between 1903 (Meiji 36) and 1941 (Showa 16), usage increased more than tenfold. The use of inorganic fertilizers exceeded that of organic fertilizers by the late 1920s. By the late 1930s, Japan ranked fifth globally in per-acre fertilizer consumption.6

This spectacular rise was far from a sure thing. Artificial fertilizer companies had to overcome significant hurdles. These hurdles are of great interest because they reveal insights into life in rural Japan during the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Remote and Isolated

The first hurdle that companies had to overcome was the lack of a nationwide distribution system. Distribution channels had been developed for organic commercial fertilizers such as dried fish and night soil. But these were mostly limited to areas that grew commercial crops, especially in Western Japan.

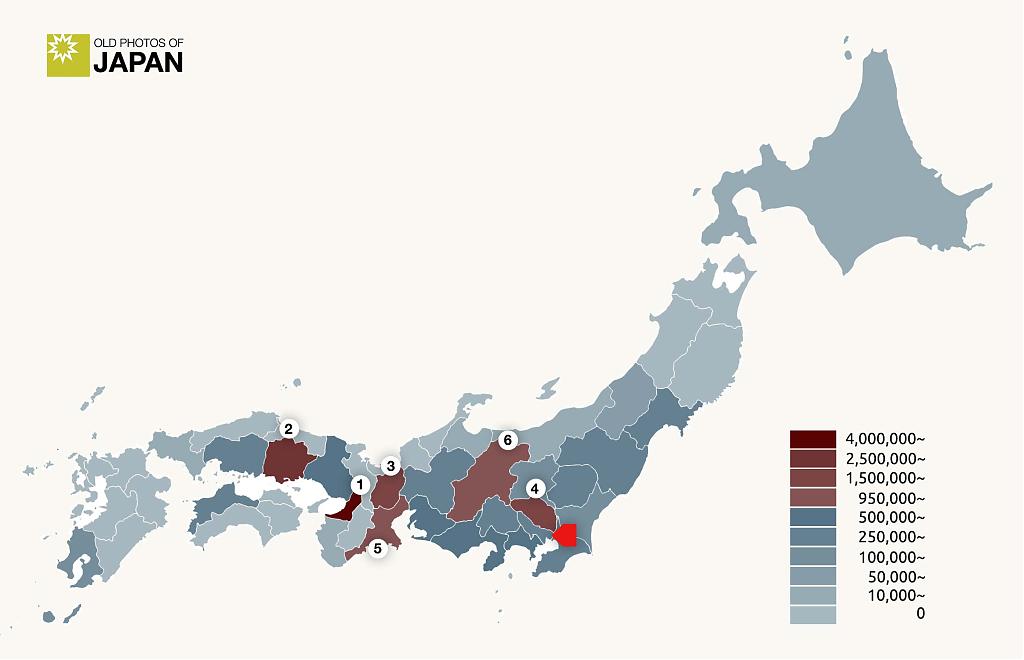

In 1887, a Tokyo based fertilizer merchant reported that almost 68% of sales were concentrated in just six of the 29 prefectures covered by the survey: Osaka, Okayama, Shiga, Saitama, Mie, and Nagano. Fertilizer sales were especially strong in Osaka because generations of farmers had grown cash crops such as cotton, indigo, tobacco, and hemp.7

Sales were almost nonexistent in isolated areas such as Toyama, Niigata, Wakayama and Yamaguchi. The remaining 18 prefectures were not mentioned at all. As the map below clearly illustrates, few if any sales were made along the coast of the Sea of Japan.8

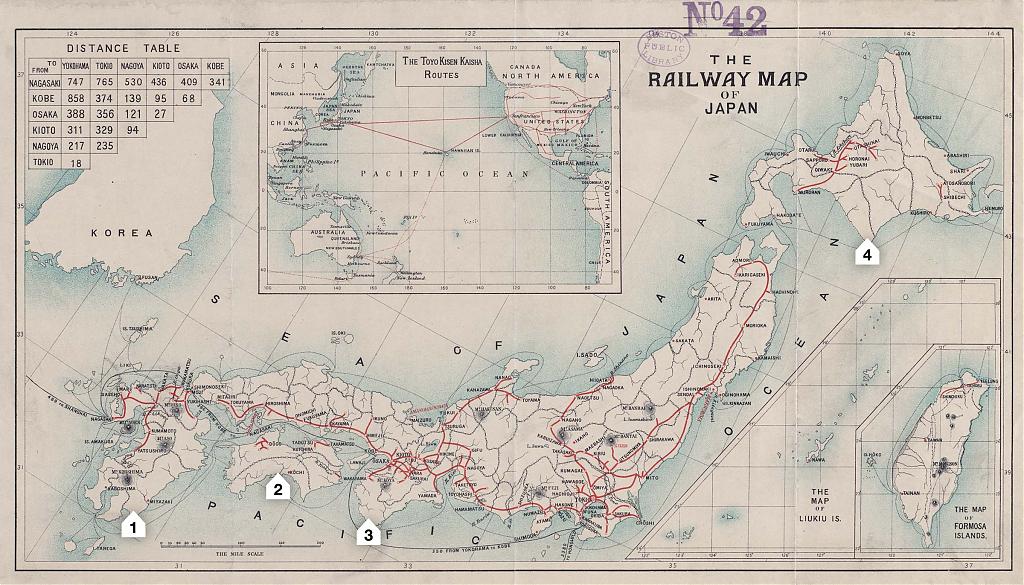

Distribution was complicated by Japan’s mountains, which split the nation into two. Even in 1900 (Meiji 33), almost three decades after Japan’s first railway, train lines reached mainly the Pacific Ocean side of the country. The Sea of Japan side, across the mountain range dividing Japan, had almost none.

This was also true for outlying areas like Hokkaido, the Kii Peninsula, Shikoku, and Kyushu. Much of Japan only became accessible by train in the 1920s.

When you compare the 1900 railway map above with the earlier distribution map, you will notice a clear overlap. These two maps effectively highlight the areas where things were happening in Japan. Many other areas were remarkably isolated. Since transportation was primarily on foot, it could take residents of truly remote areas days to reach a developed town.

Once a railway reached a new area, it drastically transformed local life and commerce, bringing both the fruits and ills of modern capitalism. As the local economy changed from self-sufficiency to monetary, people had to work for cash.

In his 1931 (Showa 6) novel Cotton (綿, Wata), proletarian writer Zentarō Taniguchi (谷口善太郎, 1899–1974) depicts such changes in a village in the Hokuriku region. He drew on his own experience growing up in a poor family in the area. His father was a tenant farmer, while his mother supported the family by carrying firewood at a nearby pottery factory.9

When I looked more closely, it became clear how much had changed since my childhood. A few years earlier, a railway had been built along the coast, about three ri from the village [one ri being the distance one walks in an hour, roughly four kilometers]. From the mountain behind the school, I could see the trains passing along the shore, trailing white smoke. They looked so small from there. The year before last, the Y copper mine opened deep in the southern valley beyond the mountains. In my own village, a pottery factory and a silk mill were built three years ago, many men and women work there. The village now has a kimono fabric shop, along with a barber shop, a general store, and a confectioner’s. Tengu-brand cigarettes have disappeared, you only see government-issued cigarettes. Traditional andon lanterns have given way to Western-style kerosene lamps, and plain indigo handwoven kimono cloth has been replaced by fancy patterned fabrics. Instead of spinning wheels and looms, silkworm racks now occupy the houses, while mulberry groves have replaced cotton fields. The village roads have been widened, and the bridge newly rebuilt. “Civilization” is indeed reaching even this remote and lonely village.

Both cotton and railways are deeply symbolic in this passage. Cotton had long been grown in Japan, but after the country opened to international trade in 1859 (Ansei 6), cheap imports flooded the market. This crippled small farmers, eroding rural livelihoods.

Many turned to silk production instead, planting mulberry trees and feeding their leaves to silkworms raised in trays within their homes. The government actively urged this shift, relying on silk exports to help finance the nation’s modernization.

Railways were a double-edged development. They gave farmers access to distant markets, enabling a shift from subsistence to commercial agriculture. But they also accelerated industrialization, intensified competition, and deepened dependence on a cash economy.

The railways were essential for fertilizer companies. It allowed them to reach their customers, while the spread of commercial crops enabled farmers to earn the cash needed to buy fertilizer. Which takes us to the fertilizer companies’ next hurdle: many Japanese farmers were struggling and couldn’t afford fertilizers.

Coming Soon : Barely Surviving.

Related Articles

Notes

1 Notable People: Jokichi Takamine. University of Glasgow. Retrieved on 2025-08-14.

The Dai-Nippon Artificial Fertilizer Company (大日本人造肥料株式会社, Dai-Nippon Jinzo Hiryo K.K.) was founded in 1887 (Meiji 20) as the Tokyo Artificial Fertilizer Company (東京人造肥料会社), and renamed in 1910 (Meiji 43). In 1936 (Showa 11) it became Nissan Chemical (日産化学株式会社, Nissan Kagaku K.K.).

2 Takamine graduated in 1879 (Meiji 12).

3 Doctor Takamine: Key Dates. Retrieved on 2025-10-05.

ALSO: Takehara, Masaatsu; Hasegawa, Naoya (2020). Jokichi Takamine: From Bioscience to the Intellectual Property Business (pdf) in Sustainable Management of Japanese Entrepreneurs in Pre-War Period from the Perspective of SDGs and ESG. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 97–110.

4 Freeman, Michael (2024). The history of fertilizers: Volume 1. Argus Fertilizer Focus magazine, 23.

5 『大阪府寫真帖』Osaka Prefecture (1913), 58.

6 Johnston, Bruce F. (1962). Agricultural Development and Economic Transformation: A Comparative Study of the Japanese Experience. Food Research Institute Studies, Stanford University, Food Research Institute, vol. 3(3), 231–232.

7 Partner, Simon(2004). Toshié: A Story of Village Life in Twentieth-Century Japan. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University Of California Press, 7.

8 渡辺徳一 (1968)『現代日本産業発達史 第13』東京, 現代日本産業発達史研究会, 86.

「進地帯においては幕末より魚肥を中心として確立されてきた流通機構があり、後発企業としてそれを把握できなかったことにあるとおもわれ る。このころの購入肥料の地域別普及度をしめす数字は乏しいが、明治 二〇年九月、農商務省が東京日本橋の井田商店にその製造する化学肥料 の販路を照会したのに対する返書によっても(表1-31参照)、東北日本と西南日本とでは顕著な差異があること、東京人造肥料は肥料の流通組織の未確立な地域における限界需要を把握したにとどまることがわかる。したがって、ここで在来の流通方法の利用がはかられることになった のである。

当社は営業不振の善後策について種々調査の結果、・・・・・・我邦在来の肥料は、 概ね買次人の手に依り需要者へ貸付売をなす慣行であったので、その方法に依らざれば自然敬遠されることが判った。依つて当社は、止むなくその旧慣に追従して貸売を始め、巡廻員制度を設けて、福島県以下十五県へ派遣し、肥料の普及宣伝と貸売とを兼ね行はしめたのである。

その後、日清戦争の開始により、満州からのダイズかす輸入が途絶し、かつ北海道での不漁のため魚肥が不足し、その結果、化学肥料需要が急増し、過リン酸肥料の販売が軌道に乗り(表1-32参照)、業績も向上し、事業の基礎が安定するにいたった。」

Data: 井田商店化学肥料府県別出荷量(匁)

Fukushima is listed twice on the table in this book, once with 324,000 and once with 24,000. The map in this article has been colored with the higher figure. The original source also lists Fukushima twice: 日本常民文化研究所ノート 第28, 日本常民文化研究所, 昭和17.

9 谷口善太郎(1963). 『谷口善太郎小説選』新日本出版社, 32.

「注意して見ると、確かに世間はわたしの幼い時より変 わっていた。村から三里ほど離れた海岸線を、数年前に汽 車が開通していた。学校の上の山へ登ると、海岸線を白 い煙を吐いて通る汽車が小さく見えた。一昨年から、山を越えた南の谷の奥にY銅山が出来た。自分の村にも三 年前から陶器工場と製糸場が出来てたくさんの男女がそこで働いている。村には呉服屋が出来、床屋が出来、雑 貨屋が出来、菓子屋が出来た。天狗印の私製たばこが彫 をひそめ、代わって「お上」のたばこが幅をきかせている。行燈が洋燈になり、ベタ紺の手織着物が、編や飛白の「呉服」に変わった。絲車や手織機の代わりに養蚕の棚が家の中を占領し、綿畑の代わりに桑畑が出来た。村の 道路が拡張され、橋が新しく架け代えられた。

確かに「文明」はこの寒村へもはいって来ている。」

Information about Taniguchi’s parents: 加藤則夫 (1977)『谷口善太郎年譜』論究日本文学 40 31-43, 1977-05, 立命館大学日本文学会.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Osaka 1913: Japan's Green Revolution (1), OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/979/farming-green-gevolution-in-meiji-japan

Ted T.

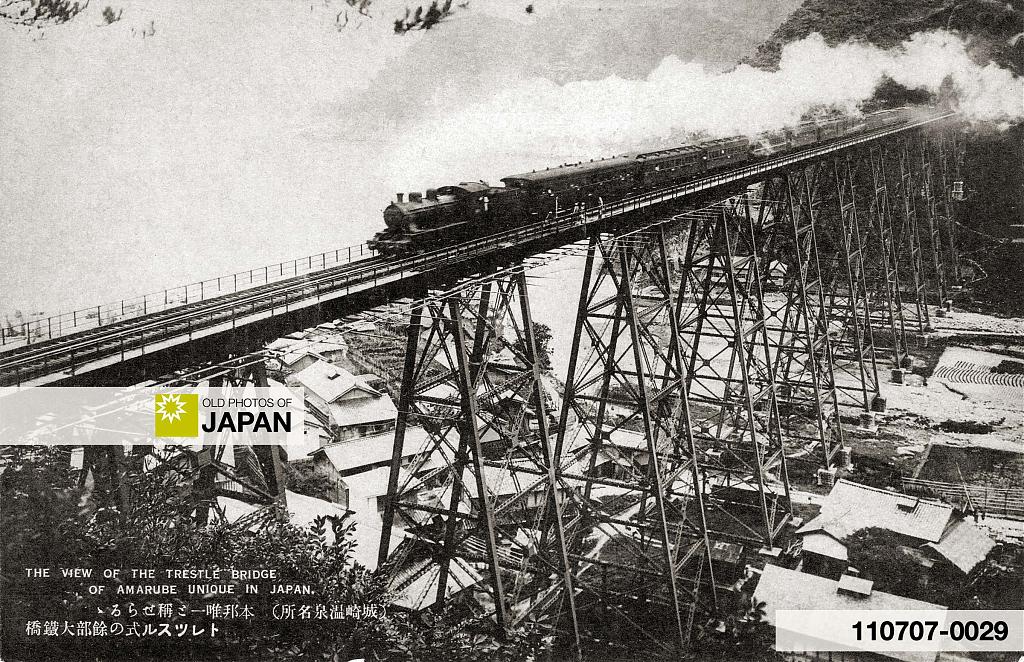

The sight of the Amarube Bridge always brings chills. I rode over it a number of times when I lived in Tottori. Passing through there a few years ago, I noted a concrete one had been built, in 2010.

#000891 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

@Ted T.: It was something truly special, wasn’t it! I can just imagine how it must have awed people when it was first built. I first saw the Amarube Bridge in the early 1980s. I never crossed it. Just saw it from below and wondered if it could withstand a strong earthquake…

#000892 ·