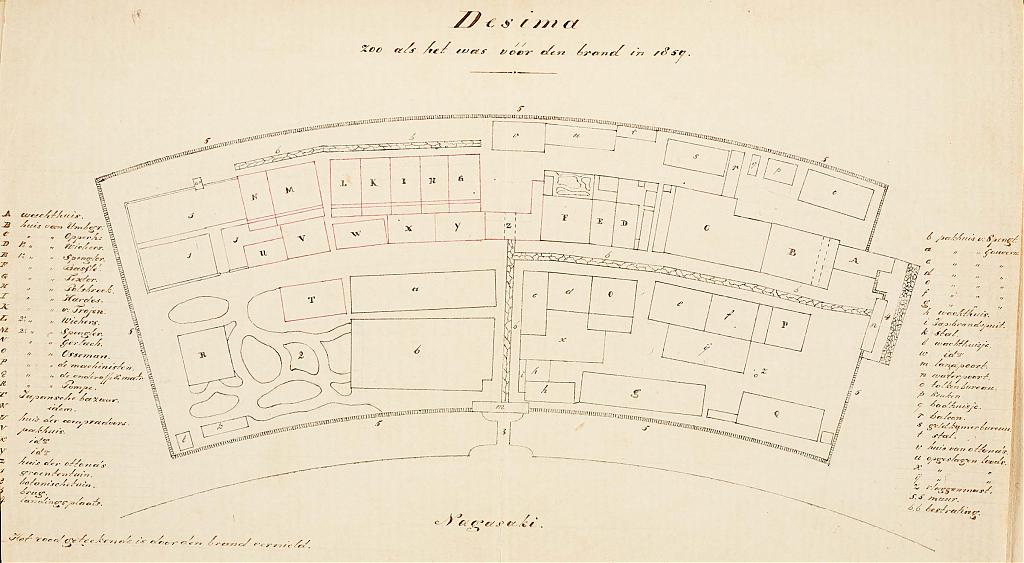

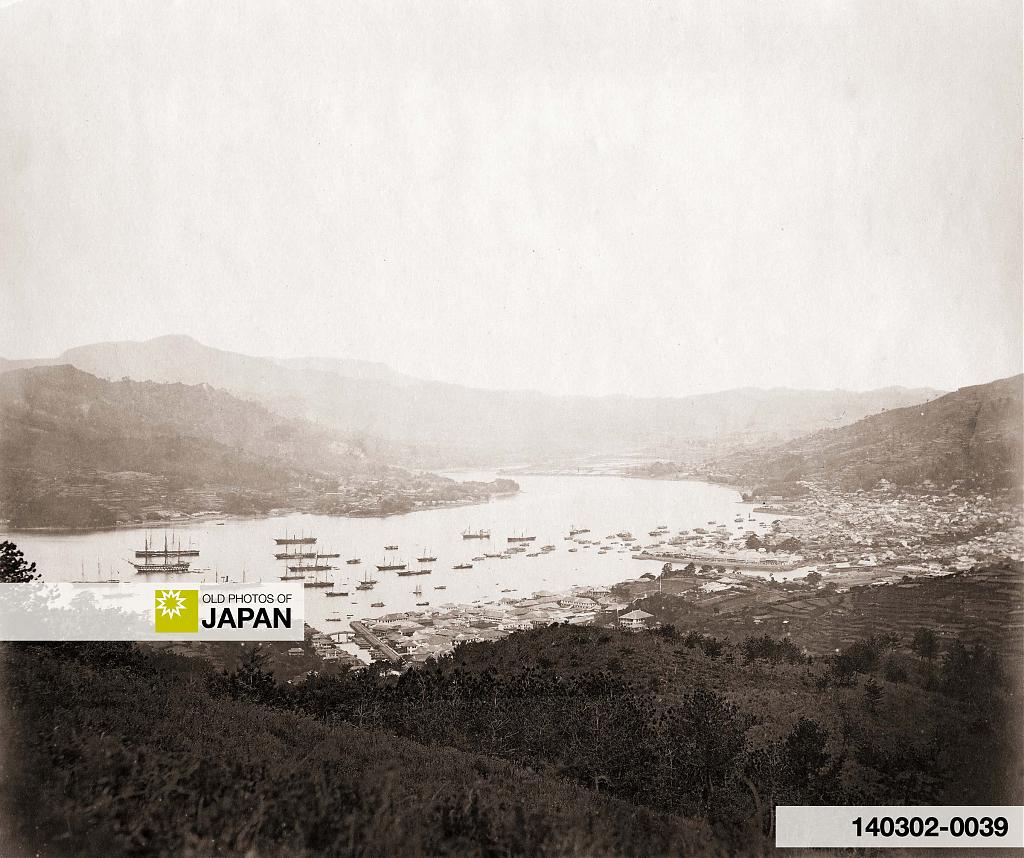

A rare early photograph of Dejima, the fan-shaped artificial island in Nagasaki. Dejima played a critical—but now largely forgotten—role in the opening of Japan to the outside world.

Dejima (出島) is now best known as the location where Dutch merchants ran an exclusive trading post during a time when Japan had closed itself from the outside world. But in the 1850s, this tiny isolated island actually played a crucial role in opening Japan to the outside world.

Dejima began life in 1634 (Kan’ei 11). The Japanese shogunate had become increasingly worried about Catholic missionary work promoted by the Portuguese in Japan, and the political consequences of large numbers of Catholic converts.

To keep the Portuguese in check, that year shōgun Tokugawa Iemitsu (徳川家光, 1604–1651) ordered the construction of a heavily guarded small artificial island in Nagasaki where the Portuguese traders could be isolated from their surroundings. The restriction of their freedom of movement however did not lead to the suppression of Christianity that the shogunate had hoped for.

So in 1638, after a rebellion by Catholic converts, the shogunate decided to end Portuguese trade. A year later, it prohibited the entry of Portuguese vessels into Japanese waters. Dejima, built at great expense, lay empty with no obvious use.

It didn’t take long though before the Japanese government found a new way to use the island. The Portuguese were not the only Westerners in Japan. In 1609 the Dutch had opened a trading post in nearby Hirado. The British followed in In 1613, but they were unsuccessful and the trading post was closed in 1623.

Even after the Portuguese were kicked out, the Dutch were allowed to stay—they limited their activities solely to trading and showed no interest in winning souls for the church. However, in 1641 they were forced to tear down their brand new brick trading post in Hirado and were moved to Dejima where the shogunate could better control them. This control was so strict that they were barely allowed off the island, while only a small number of carefully observed Japanese were let in.

Between 1641 and 1856, the Dutch traders were the only Westerners allowed in Japan, creating a unique exclusive relationship between the Netherlands and the Japanese shogunate. It was during this isolationist period that Dejima turned into a crucial window on the West through which Western medicine, science and technology—including military technology—were introduced into Japan. This became known as Rangaku (蘭学, Dutch studies).

Opening Japan

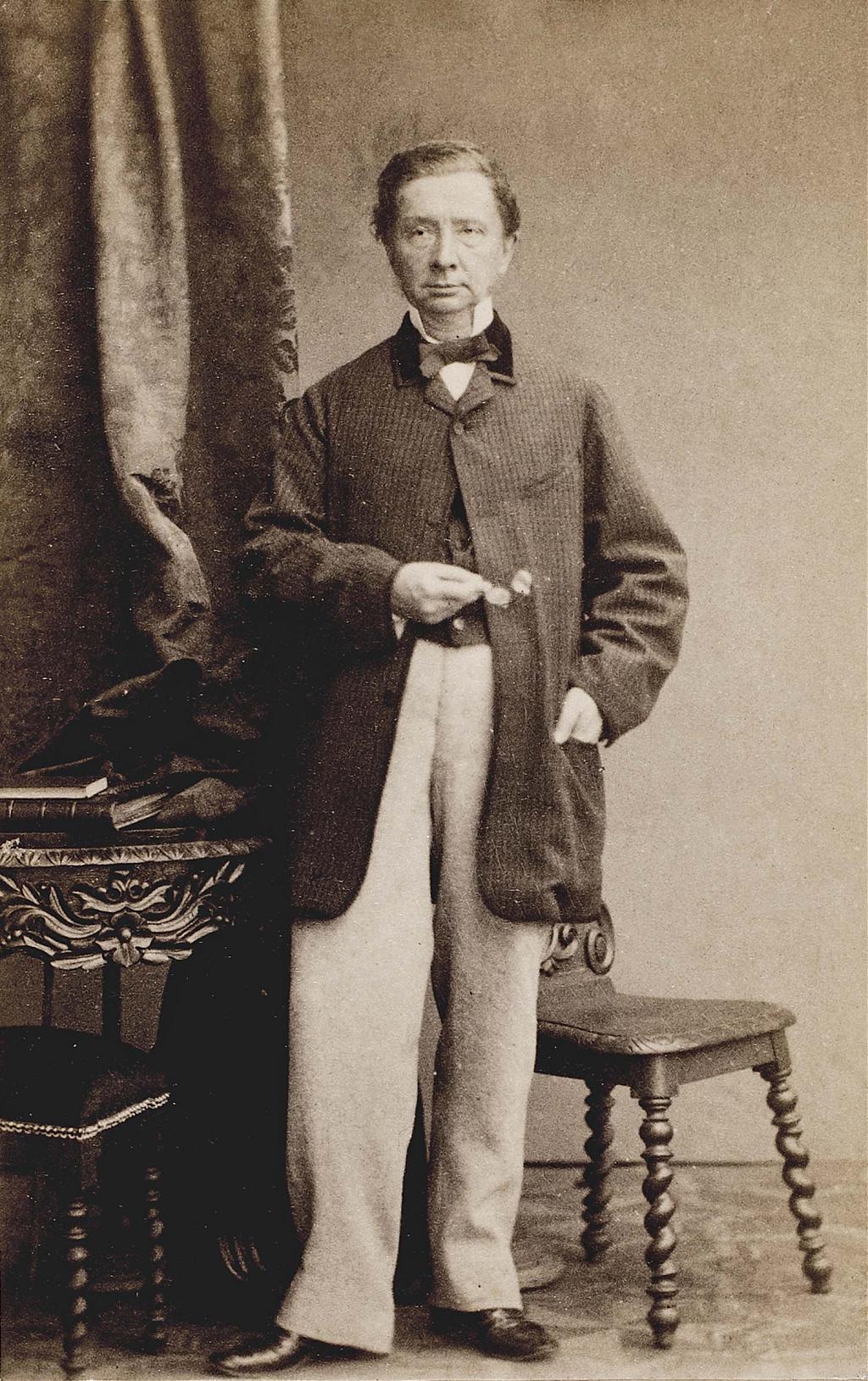

The Dutch trading station at Nagasaki’s Dejima island was run by a chief agent (or “Opperhoofd”) who was not a political representative.1 This changed in 1855, when the last Opperhoofd, Jan Hendrik Donker Curtius, received the title, “Dutch Commissioner in Japan,” making him the first Dutch diplomatic representative in Japan.

It was because of this appointment that Dejima ended up playing a central role in the opening of Japan. Donker Curtius was—although this is mostly forgotten—the first foreign diplomat to conclude a commercial treaty with Japan. He did this nine months ahead of American Consul Townsend Harris, who has gone into the history books as having opened Japan to foreign trade with the Harris Treaty.

When Donker Curtius was appointed Opperhoofd in July 1852, the Dutch government had become deeply worried that Great Britain and the United States would use military force to bring Japan’s two-and-a-half century old policy of isolation to an end. This could embroil the neutral country in war.

It therefore tasked Donker Curtius to persuade Japan to open its ports to international trade without resorting to force. Dutch Minister of Colonies Charles Ferdinand Pahud (1803–1873) wrote a secret letter to Dutch King Willem III that explained the course of action. “No threat whatsoever” was allowed. Additionally, “no intervention should be offered, nor should any side be chosen, between Japan and the attackers, in the event of hostilities.”2

A previous attempt had failed dismally. In 1844, King Willem II had sent the shogun a letter, “from king to king,” advising that it was in Japan’s best interest to open its borders to free trade. The suggestion had been categorically rejected, and the Dutch were told not to send such a letter again.3

In other words, Donker Curtius had been handed a nearly impossible assignment. Even more so because he was not a diplomat. He was a jurist, employed by the colonial government in the Dutch East Indies.

Negotiations

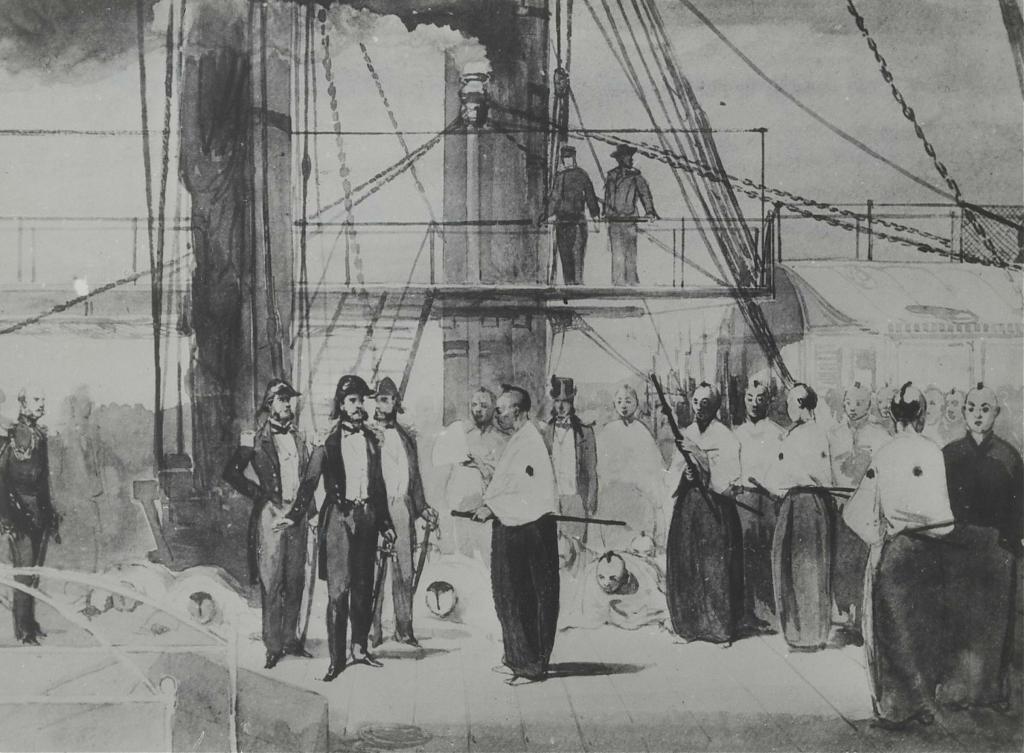

The first opportunity to negotiate conditions for a treaty offered itself when American Commodore Perry visited Japan in 1853 (Kaei 6) with a threatening fleet of modern warships. Perry demanded that Japan open its borders. He would return the following year for the answer. Although the Dutch government had informed Japan of the expedition well in advance, it still unnerved the Japanese government. The shogunate turned to Donker Curtius to order seven warships, a large number of firearms, and books on military subjects.4

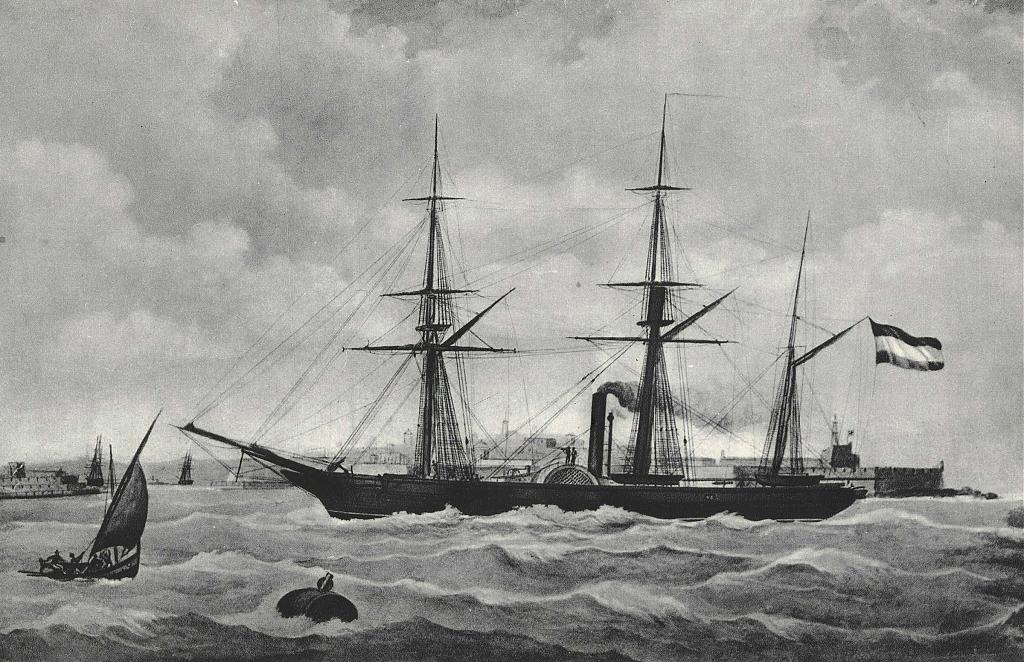

The Netherlands responded by offering the steam warship Soembing as a gift from King Willem III in 1855. The Japanese renamed it Kankō Maru (観光丸). As it was Japan’s very first steam-powered warship, Japan needed teachers as well. So Donker Curtius simultaneously arranged that a Dutch naval detachment was invited to teach the Japanese how to use their gift.

Naturally, these officers had to be treated with respect and dignity, and needed to move around freely. The strict rules that had confined the Dutch on Dejima for over two centuries were ended. In January 1856, a Dutch-Japanese Friendship Treaty was concluded that encoded these new rights.

Donker Curtius then used this treaty to negotiate additional articles allowing trade in Nagasaki and Hakodate. Signed on October 16, 1857, traders from other nations were also allowed to trade under this treaty, long before these countries concluded their own treaties with Japan.5

Donker Curtius actually helped American Consul Harris to conclude his treaty. He regularly communicated with the American consul and even sent a copy of the additional articles soon after they were concluded in 1857.6 Undoubtedly more important were the discussions that Donker Curtius had with Nagasaki officials about the Second Opium War (1856–1860) that Great Britain and France waged against China.

Donker Curtius’ report of this conflict showed Japanese officials how Great Britain twisted a small incident into an excuse to start a war. His report was widely circulated and greatly influenced Rōjū Hotta Masayoshi (堀田正睦, 1810–1864), who played a crucial role in the negotiations with Harris. Thanks to Donker Curtius’ explanations, Hotta had a thorough understanding of the causes of the war, and the dangers to Japan of ignoring or insulting Harris.7

It is in no small measure thanks to this understanding that Harris was eventually allowed to visit Edo (present-day Tokyo). Here he was able to conclude a treaty that reached much farther than what Donker Curtius had achieved. It opened several ports and can be seen as the start of free international trade in Japan.

Opperhoofd’s Residence

As a result of the appointment of Donker Curtius in 1855, the residence of the Opperhoofd became the first Dutch diplomatic mission in Japan, arguably the first foreign one.

The two-storied Opperhoofd’s residence was located very close to the Water Gate, one of only two entrances to the island. Dutch naval officer Hendericus Octavus Wichers who lived at Dejima between 1857 and 1860, described the approach to the building in his diary:8

When one goes from the roadstead to Desima [sic], one enters that island through the Water Gate, a gate which was formerly open only during the unloading and loading of ships, but now remains open from morning to night and is only closed at night. Straight ahead, one now sees a fairly wide street, paved in the middle with large elongated stones. On the right side, first a Japanese guardhouse, intended for the officer of the watch who is always there when there are Japanese, coolies, and workmen at Desima. We call him Opperbanjoo[s]t. Next, an empty house formerly occupied by the Master of the Storehouse, then the house of the Opperhoofd.

Wichers writes that the houses at Dejima were built using traditional Japanese construction methods. They were timber framed with walls made of bamboo, tied up with rice straw ropes, and plastered with clay. “Inside, the wall is covered with beautiful Japanese wallpaper, all the pieces a foot long and a half wide. The outside is covered with an excellent kind of white plaster, or with thin planks which are then painted black.”9

Because a devastating fire had destroyed most of the buildings on Dejima in 1798, the Opperhoofd’s residence was still fairly new when Donker Curtius arrived in 1852. It had only been completed in 180910, and appears to have been remodeled just before the arrival of Opperhoofd Pieter Albert Bik in 1842.11 Ten years later, it must still have been in a good state of repair.

Bik, who left Dejima in 1845, took a floor plan of the residence back with him to the Netherlands. So, we know how the building was used around that time. Most likely, little had changed when it became the Dutch diplomatic mission in 1855.

The floor plan shows large reception and guest halls, an office, a veranda from which incoming ships could be seen, and several private rooms, including a room for the courtesan (meidkamer). It was conveniently situated right next to the bedroom.

As was custom at Dejima, all these rooms were located on the second floor of the building. The ground floors were generally used as storage space.

Wichers, who used the residence to teach modern navigation to some thirty Japanese students, writes that it was “very spacious, and partially very decently furnished at government expense for the reception of important people, like lords, governors, etc. In one of the rooms the entire Royal family is on display in ornately gilded frames.”12

Sayonara Dejima

In 1859, once again, many buildings were destroyed by fire. The well was dry and it was low tide, so there was no water for firefighting. The flames were finally stopped because some 200 Russian sailors who had rushed in to help knocked down an old house.13

Thanks to them, the Opperhoofd’s residence survived the disaster. On a map that Wichers drew of Dejima, the houses that burned down are marked in red. It graphically illustrates that the fire came within meters of the residence.

Consul General Jan Karel de Wit gratefully took advantage of this miracle when he took over from Donker Curtius in 1860, only a year after the fire. He moved into the former Opperhoofd’s residence and made it the consulate general. When he left Japan in 1863, the consulate general was moved to Yokohama. The government furnishings that so impressed Wichers, were moved to the new location as well.

Around this time, merchants of other nationalities were starting to make Dejima their new home, while the unique position of the Netherlands in Japan was quickly fading. Following more than two centuries of continuous use, the curtain had finally closed on Dejima as a unique and exclusive Dutch home base in Japan.

After the consulate general was moved away from Nagasaki, the agent of the Netherlands Trading Society (Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij), Albert Bauduin, was appointed consul. He moved into the former Opperhoofd’s residence, which now became the Dutch consulate.

The Dutch government auctioned off the former Opperhoofd’s residence on January 16, 1865.14 Bauduin became the leaseholder. He moved to Kobe in January 1868, after which consular affairs were taken care of by succeeding employees of the Netherlands Trading Society.

It appears that the consulate remained in the former Opperhoofd’s residence through December 16, 1874, when Consul Johannes Jacobus van der Pot handed consular services over to Marcus Octavius Flowers, the Consul of Great Britain.15 In a letter dated January 5, 1875, Van der Pot wrote that the flagpole of the consulate at Dejima had been moved off the island to the Netherlands Trading Society office at number 5 in the foreign settlement of Oura.16 A truly symbolic farewell.

Adapted from From Dejima to Tokyo (2022), the first complete history of Dutch diplomatic locations in Japan. The study was commissioned by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Tokyo and researched and written by Kjeld Duits.

Notes

1 Dutch trade relations were based on a document that Shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu had given to Dutch merchants in 1605. The first dutch trading station was set up at Hirado in Nagasaki. The Dutch were moved from Hirado to Dejima in 1641. The Dejima trading post was administered by a chief agent (Opperhoofd), since 1800 appointed by the Dutch colonial government in Batavia. Officially, the Opperhoofd was not a diplomatic representative of the Netherlands.

2 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.01 Inventaris van het archief van het Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken, 1813-1870: 3141 1852 feb. – 1859 okt., 0034–0045. Secret report of March 21, 1852, from Ministry of Colonies to King Willem III:

“De Gouverneur Generaal is van oordeel dat met het vooruitzicht op die eventualiteit, onzentwege pogingen zouden behooren te worden aangewend om de Japansche Regering tot het aannemen van een ander stelsel te bewegen, en, bij mislukking daarvan, liever Japan geheel re verlaten, dan ons bloot te stellen aan het gevaar om te worden gebragt in het alternatief om of oorlog te voeren tegen machtige Staten, of dezen de behulpzame hand te bieden in den maatregelen van geweld, welke zij tegen Japan zouden nemen.

1o. om den Gouverneur Generaal te magtigen door middel van het nieuw te benoemen Opperhoofd van den handel op Japan, bij de Japansche Regering, door een schrijven van hem, Gouverneur Generaal aan te dringen, of althans een ernstig vertoog te doen, ten einde die Regering een ander stelsel aannemen dan zij tot dus ver heeft gevolgd, bij welk vertoog zal moeten worden gewezen op den zoo welmeenend door Zijne Majesteit Koning Willen II in 1844 gegeven raad, en op de waarschijnlijk spoedige verwezenlijking van de destijds voorspelde gebeurtenissen, hetgeen uit de maatregelen, welke in Noord-Amerika worden beraamd duidelijk is.

2o. om verder aan den Gouverneur Generaal te kennen te geven dat aan de Japansche Regering bij gelegenheid der boven bedoelde mededeelingen, geenerlei bedreiging moet worden gedaan, en ook niet tot het afbreken der betrekkingen met Japan, of het intrekken der Faktory te Decima moet worden overgegaan, ten ware de loop der gebeurtenissen zulks gebiedend vorderen en onvermijdelijk maken moet voor de eer en waardigheid van de Nederlandsche Regering, dat geen tuschenkomst aangeboden en ook geen partij gekozen moet worden tuschen Japan en de aanvallers ingeval het tot vijandelijkheden komen moet, maar dat, ingeval onze tuschenkomst mogt worden ingeroepen, getracht moet worden, die tot eene gewenste en goede uitkomst te doen strekken.

3o. Om de Nederlandsche Legatie bij de Vereenigde Staten van Noord Amerika bekend te maken met den brief in 1844 door Z. M. Koning Willem II aan den Keizer van Japan geschreven, ten einde daarvan, op eenen geschikte wijze, gebruik te kunnen maken om het Amerikaansche Gouvernement op de hoogte te stellen van de demarches reeds toen door Nederland gedaan, om de Japansche Regering tot andere beginselen te nopen.”

3 Jacobs, E. (1990). Met alleen woorden als wapen. De Nederlandse poging tot openstelling van Japanse havens voor de internationale handel (1844). BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review, 105(1), 54–77.

4 McOmie, W. (2006). The Opening of Japan, 1853–1855: 10 The Dutch, British, Russians (and Americans) in ‘Opened’ Japan. Leiden: Brill, 326–372.

5 Pompe van Meerdervoort, Jhr. J. L. C. (1868). Vijf jaren in Japan. (1857-1863): Bijdragen tot de kennis van het Japansche keizerrijk en zijne bevolking. Tweede Deel. Leiden: Firma Van den Heuvel & Van Santen, Hoofdstuk VI, 14.

6 Nakanishi Vigden, Michiko (October 1987). Bulletin of the Japan-Netherlands Institute Vol. 12 No. 1 (No. 23). The Correspondence between Jan Hendrik Donker Curtius and Townsend Harris (47–78), 53.

7 Masuda, Wataru, Fogel, Joshua A. (2000). Japan and China: Mutual Representations in the Modern Era. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 46.

8 Wichers, Hendericus Octavus. Oorzaken der komst van een detachement van de Koninklijke Nederlandsche Marine in Japan, 1855-1860, B II 108 A, National Maritime Museum Amsterdam, 22.

9 ibid, 23.

10 Nagasaki City Council on Improved Preservation at the Registered Historical Site of Deshima (1987). Deshima: Its Pictorial Heritage, Nagasaki City, 296.

11 ibid, 297.

12 Wichers, Hendericus Octavus. Oorzaken der komst van een detachement van de Koninklijke Nederlandsche Marine in Japan, 1855-1860, B II 108 A, National Maritime Museum Amsterdam, 11–12.

13 ibid, 92.

14 Algemeen Handelsblad. Amsterdam, March 4, 1865, pp. 2. Also Nationaal Archief. 2.05.10.08 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan, 1879-1890, 28: 0734 and 0736.

15 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.10.08 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan, 1879-1890, 29: 0451.

16 Nationaal Archief. 2.05.10.08 Inventaris van het archief van het Nederlandse Gezantschap in Japan, 1879-1890, 36: 0009.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Nagasaki 1865: Dejima Island, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on February 22, 2026 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/904/dejima-island-nagasaki-19th-century-vintage-albumen-print

Ilshat Khusnutdinov

Wasn’t the Treaty of Shimoda between Japan and Russia (January 1855) concluded earlier than the Harris Treaty or the Dutch-Japanese treaty?

#000844 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

@Ilshat Khusnutdinov: Excellent observation, Ilshat. It is easy to get confused by all the different treaties.

The Treaty of Shimoda between Japan and Russia of February 7, 1855, opened the ports of Nagasaki, Shimoda and Hakodate to Russian vessels, established the position of Russian consuls in Japan, and defined the borders between the two countries.

So yes, it was concluded earlier than the Harris Treaty and the Dutch-Japanese treaty, but it was a treaty for opening ports and establishing the position of consuls like the earlier Japan–US Treaty of Peace and Amity signed on March 31, 1854.

It was not a trade treaty like the 1857–1858 treaties discussed in this article.

#000845 ·