Hi, I am Kjeld Duits, the person behind Old Photos of Japan.

When I moved to Japan in 1982, most of the tools and routines that once shaped daily life — and even much of the traditional architecture — had already vanished, swept away by the modernization that began in the 1850s.

To bring this cultural memory back into public view, I began collecting, researching, and sharing old photographs in 2007. Over the years, I added vintage maps, art prints, and other materials. Today, the Duits Collection holds nearly 10,000 original items and 50,000 digital files from fellow collectors.

As the project enters its 20th year, its scope has grown beyond what a single person can sustain. Preserving, researching, and sharing this history now depends on broader support. Discover what makes this work important, and how your support can ensure it continues:

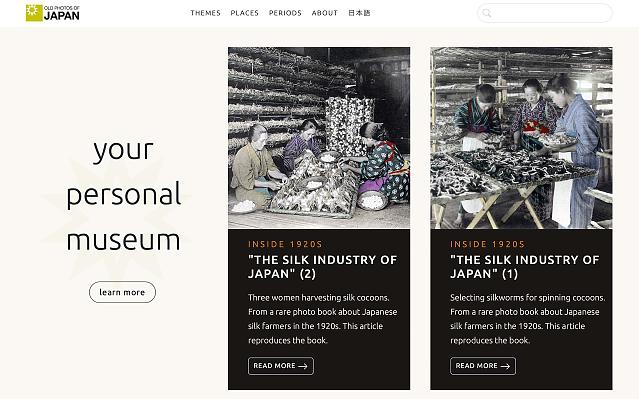

What Is Old Photos of Japan?

Old Photos of Japan preserves the cultural memory of daily life in old Japan and shares it freely with the public — your personal online museum of lived history.

The project rests on three pillars: