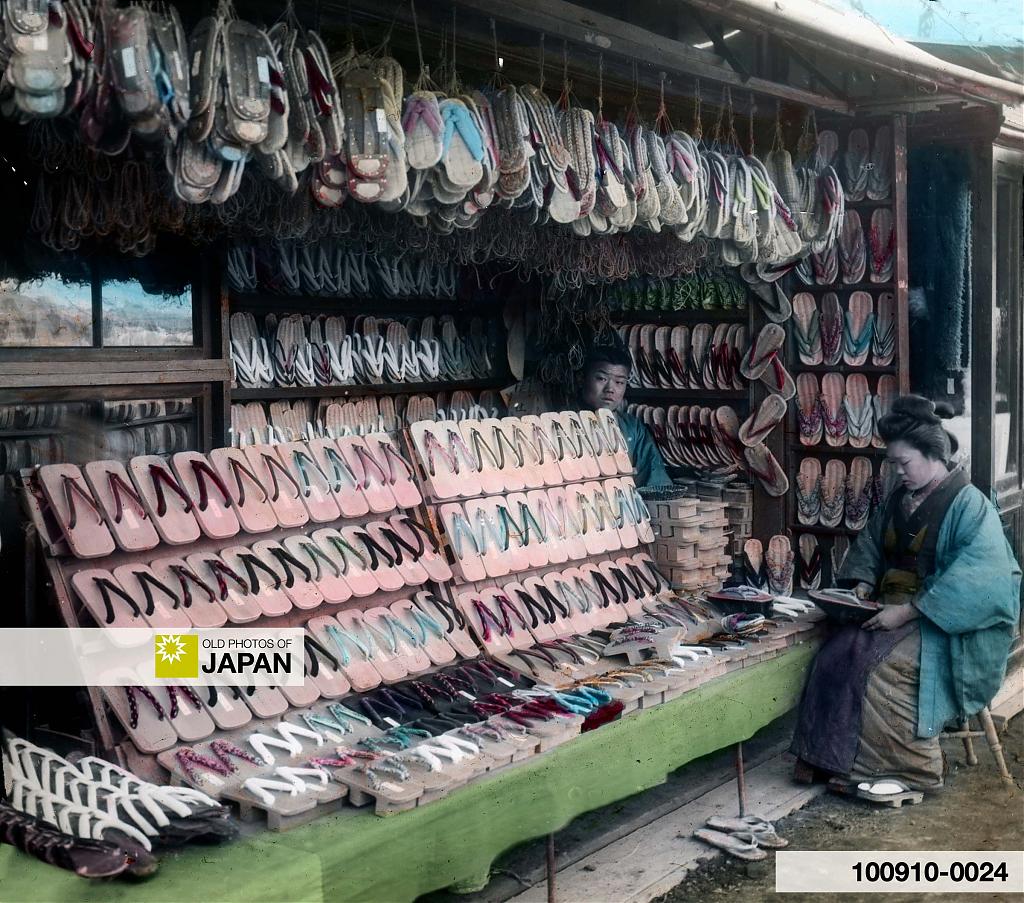

A small geta and zori shop. The shopkeeper is working on a geta while a customer is looking on. Shops like these were once everywhere in Japan.

The shop is overflowing with merchandise. The most common geta are front left, while matted geta can be seen on the right. Matted zori (sandals) are hanging from the ceiling. The store also sells bangasa (番傘, oiled paper umbrellas), seen on the right of the shopkeeper.

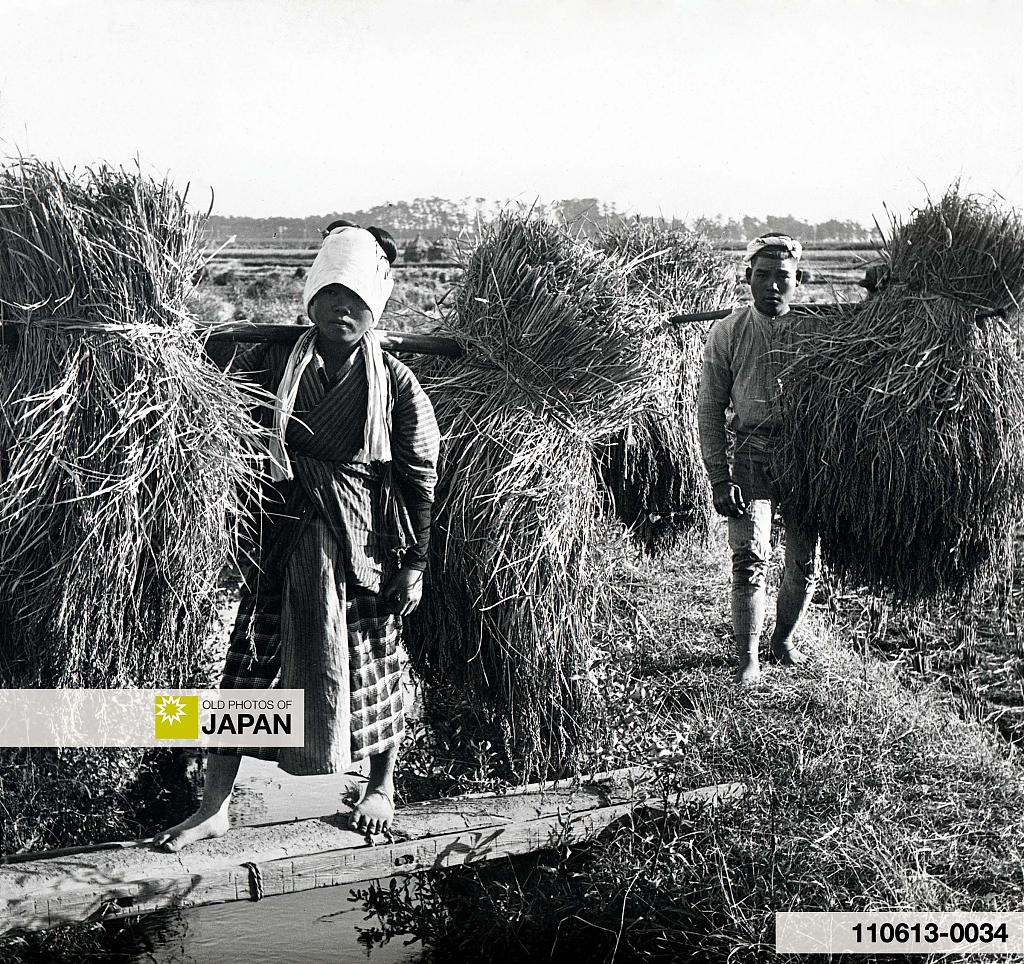

The roots of geta go back to the Yayoi period (300 BC–300 AD). This long history didn’t automatically translate into popularity though. Well into the Meiji period (1868–1912), a large part of Japan’s population went barefoot, or wore waraji (草鞋, straw sandals).

This was especially the case in the countryside, as can be seen in countless photographs. Something very interesting becomes apparent when one observes these photographs: more men than women seem to wear waraji.

It is no surprise that waraji were so common in the countryside. The straw sandals were especially suited to running, long walks, and any work that required long periods of being on your feet. They had a drawback in wet conditions though, explained Japanese author Jukichi Inouye in Home Life in Tokyo (1910):1

They are worn by coolies and others whose business it is to be constantly on their feet. Unfortunately, they soon become sodden in rain or over a muddy road; but as they are very cheap, they are frequently changed in a long journey. Cast-off straw-sandals are among the commonest sights on the road on a rainy day.

Many people who usually wore waraji, did own geta. But they were mostly worn on special occasions, like matsuri (religious festivals).2

Meiji Footwear Shift

Starting in the Meiji period, a dramatic footwear shift took place. People who used to go barefoot started to wear waraji, while those who wore waraji changed to geta or even shoes or boots.

Several trends combined to create this shift. One was a great increase in other straw products. Straw ash was increasingly used to make fertilizer, for example. The demand for tatami rice mats also rose significantly, especially in the city. But even in the countryside, more houses started to have tatami rooms. Additionally, the demand for straw to make paper went up, and Japan’s expanding military force required straw to feed its horses.3

There was also an increased focus on sanitation. In 1901 (Meiji 34), the police issued an order that prohibited going barefoot in Tokyo in order to combat disease:4

As a precaution against the plague, it is forbidden to walk barefoot outdoors in the city of Tokyo. Violators of this order will be arrested and punished in accordance with Article Four, Section 426, of the penal code.

The timing of this shift was excellent for geta, which had just come into wider use towards the end of the Edo period (1603–1868). During the Meiji period, geta were produced in increasingly larger numbers. This lead to many more paulownia trees (桐, kiri) being planted in Japan, as this was the best wood for geta.5

An interesting footnote is that, just as the paulownia’s economic importance was rising, so was its symbolic significance. After the Meiji Restoration of 1868 (Meiji 1), paulownia leaves and flowers were incorporated into the official emblem of the Japanese government. You can still find them there today.

Form and Shape

Geta craftsmen offered a wide variety of geta, depending on the fashion of the time. The most basic style is still in use to this day. It consists of a wooden board known as a dai (台), with a hanao (鼻緒, cloth strap) passing between the big and second toes. Below the dai are two ha (歯, teeth), one under the ball of the foot so it pivots while walking, and the rear one under the heel, the center of gravity.

Geta of better quality were generally sold separately from the hanao. They were fitted while the customer waited. In vintage photographs of geta shops you can usually see countless hanao hanging from the ceiling.

The forward knot of the hanao was protected in a cavity on the bottom of the geta. This was covered by a metal cap, so the knot remained clean, making it easier to replace the hanao.

Men’s hanao were covered with leather, or dark colored silk or hemp cloth, while hanao for women were mainly silk, cotton, or hemp cloth.6

The best geta were made of paulownia wood, while cheap geta used cryptomeria and other wood. The dai and ha were usually made from one piece of wood. But if they were made separately, the better ha were made of oak, and the cheaper ones of beech.7 While most geta were unadorned, geta for girls were often painted black, brown, or red. Those for very little girls often contained a tiny bell in a cavity in the bottom.8

Geta varied greatly in height. The higher ones were especially used for rainy weather. They could be as high as 15 centimeters (6 inches). Occasionally, a toe cap was used as mud guard. In the photo below, capped geta can be seen in the top right, and center left. In the top photo, toe caps are lying on the floor between the shopkeeper and the customer.

Because geta were simple, and made from natural products, they were easy to repair. As a result, geta repairmen (下駄直し, geta-naoshi) were a fixture on Japan’s streets. Shouting naoshi, naoshi (直し直し, repair, repair), they carried their tools in baskets or boxes, which were balanced on a large pole.

Their tools were simple, generally a saw (鉈), plane (鉋), hammer (金槌), chisels (鑿), as well as some spare wood and hanao to replace damaged parts. This allowed them to strike down pretty much anywhere their service was needed, and start fixing geta right away. Apparently, each repairman had its own territory.

Western Footwear

Shoes were introduced to Japan as part of the Western-style military uniform. The first order arrived during the civil war that lead to the Meiji Restoration. They turned out to be too narrow and were trashed. To solve the problem of military footwear, a shoe factory was established in Tokyo’s Tsukiji area in 1870 (Meiji 3).9

Shoes and boots didn’t catch on easily. Some groups of people adopted them, female students for example would wear shoes or boots with their hakama uniforms, and people wearing Western-style clothing—mainly men.

But Western-style footwear was initially seen as extremely inconvenient. It has always been the custom to remove footwear upon entering a house, and shoelaces made that troublesome. In 1910, Japanese author Jukichi Inouye described the social problems they caused:10

Still, boots and shoes are often unavoidable when we pay a chance visit; but then the boots should be elastic-webbed, for if we call with laced boots on, the servant who answers the door has to wait patiently in the draught until we take them off. The situation is aggravated when the visitor leaves; for then the host and his servant, and if he is a friend of the family, the wife and the children, will come to the porch to see him off and remain there until he leaves the house. If the caller has any tact, he will merely tuck in the laces and walk out with his boots flopping and tie them when he is out of the premises. Many visitors, however, think nothing of keeping the whole family shivering in the cold while they leisurely lace their boots, for probably they too are put to the same ordeal when they have visitors in laced boots.

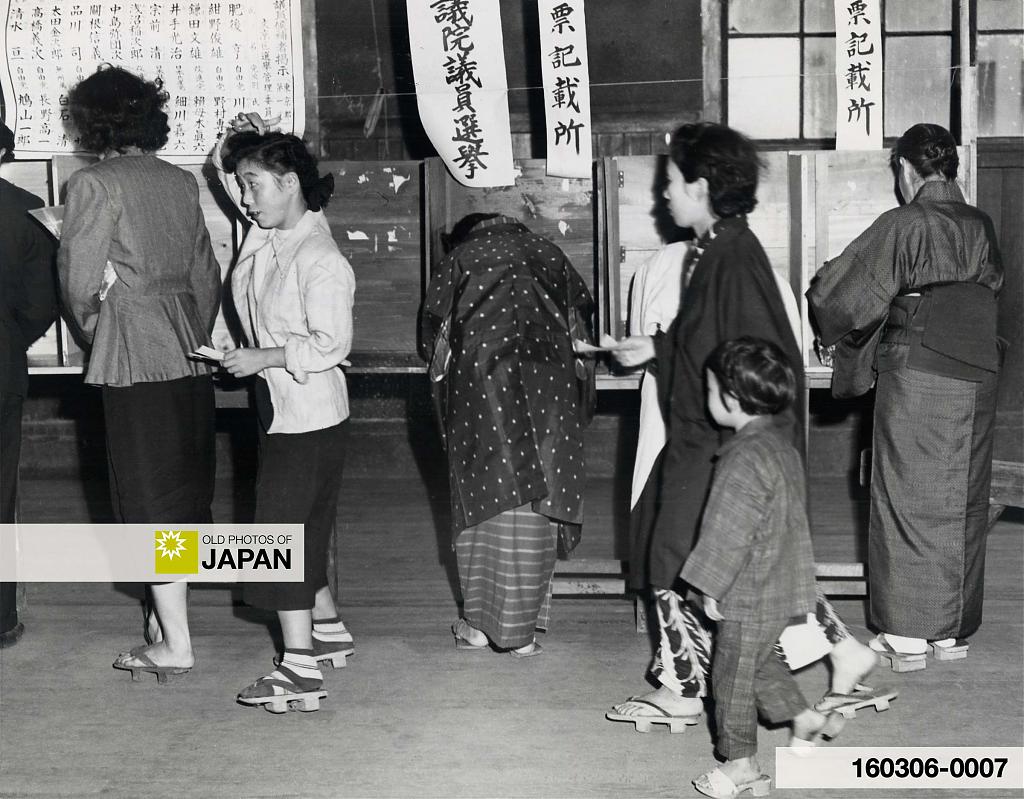

Through the early 20th century, geta and zori generally maintained their dominance, especially with women. Even at modern work places like hospitals and telephone exchanges. Japanese Red Cross nurses used geta in the operating room, while phone operators wore zori.

Geta were still common in in the 1950s. On a photo of Japanese women registering for elections in 1952 (Showa 27), every single one is wearing geta, even those in Western-style clothing. In the countryside, many people even continued to go barefoot.

But by the sixties, as the Japanese economic miracle was taking root, Western-style footwear increasingly took over from traditional Japanese styles. Soon, they had almost completely disappeared from the streets.

In the mid 1990’s, young people rediscovered geta and zori with the new popularity of yukata (cotton summer kimono).

Famous Japanese fashion brands like Kansai Yamamoto, Junko Koshino, Junko Shimada, Comme des Garçons and others created beautiful new yukata designs that attracted modern urban youths. This created a yukata boom, and a new market for traditional Japanese footwear, albeit updated to modern expectations.

Geta and zori can also still be found at many onsen ryokan (hot spring inns), where they are lend to visitors together with yukata. Some hot spring resorts, like Kinosaki Onsen (Hyogo Prefecture) and Naruko Onsen (Miyagi Prefecture), have developed their town with the premise of wearing geta. In these towns, the tourist office even offers geta rental.

When you walk down their streets, you can hear the nostalgic karan koron (カランコロン) sound of geta, just like it reverberated through the streets of old Japan.

Notes

1 Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 128.

2 Yanagida, Kunio, Terry, Charles S. (1969) Japanese Culture in the Meiji Era Vol.4: Manners And Customs. Tokyo: The Tokyo Bunko, 287.

3 ibid 280, 281.

4 ibid 21–22.

5 ibid 22.

6 Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 126.

7 ibid, 127.

8 ibid, 126.

9 Yanagida, Kunio, Terry, Charles S. (1969) Japanese Culture in the Meiji Era Vol.4: Manners And Customs. Tokyo: The Tokyo Bunko, 23.

10 Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 123.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 1920s: Geta and Zori Shop, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/897/geta-zori-traditional-japanese-footwear-meiji-taisho-showa-period

Kristin Newton

I used to have an art school in Azabu Juban. It was on the 3rd floor of a 5 story building. A family owned the building and had a kisaten coffee shop on the first floor. When I first moved it, the mother of the landlord paid me a visit and told me about how she started the kisaten after WW2. She had come to Tokyo from the countryside for an arranged marriage before the war. Her husband’s family made geta. Tokyo was bombed to rubble during the war but somehow they survived. Her parents-in-law wanted to start up their geta business again, but she had the foresight to realize that had no future. She went to night school to learn about running a coffee shop and somehow convinced the family to open one. As a young bride in the family that was quite radical for those times. None of then, herself included, had ever been in a coffee shop. It became a big success and as a result the family could buy buy land and build several buildings in Azabu Juban. They were a lovely family.

#000769 ·

Kjeld (Author)

@Kristin Newton: Lovely story. She had amazing foresight. Especially impressive as she was a young woman from the countryside just after the end of WWII.

#000770 ·

Ben G

Great article. I was stumbled upon a pair of tall geta-style sandals in Syria, and wondered what the story behind these were.

It turns out that geta-style raised footwear was common in the Levant, for use in the wet and slippery environment of hammams.

Here is an example of such footwear, from 19th century Syria:

https://assets.catawiki.com/image/cw_normal/plain/assets/catawiki/assets/2020/4/25/e/e/6/ee618192-00bb-4adf-9d8d-cc6dde43c362.jpg

#000877 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

@Ben G: Thank you for sharing. I was not familiar with Turkish bath customs. Hammam shoes, like the ones in your link, are absolutely gorgeous.

#000878 ·