Farms at Negishi in Yokohama. This beautiful rural landscape was a short distance from the foreign settlement.

Cross the mountain on the left of this image and you were on the Bluff at Yamate, where the foreigners had their luxurious homes.

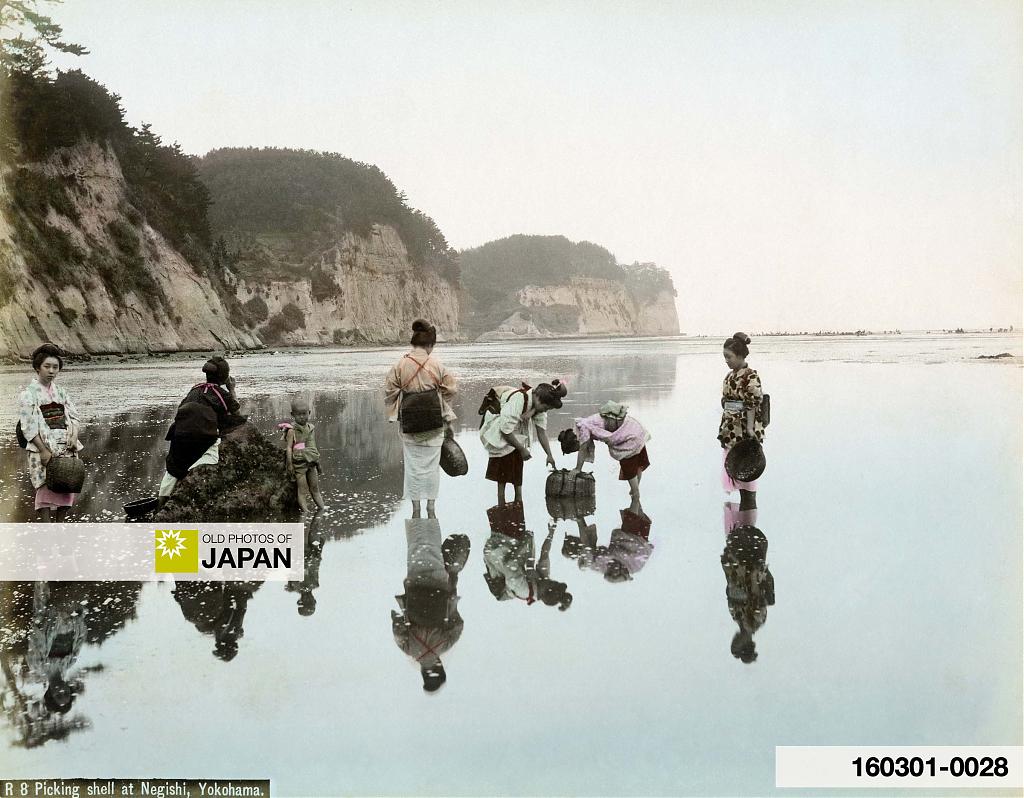

Negishi was called Mississippi Bay by the foreigners, apparently this was coined by Commodore Perry whose flagship bore that name. They also called it “the most scenic spot in the world” and would come here to enjoy the fantastic view on the sea and the faraway cliffs at Honmoku. At the foot of the cliffs, local women and children combed for shellfish at low tide.

Negishi was beautiful, but life was hard. Especially during the long hot summers when epidemic diseases wreaked havoc and a typhoon could destroy the harvest or claim the lives of farmers and fishermen. Thankfully, the inhabitants of Negishi had their Shinto priests to protect them from misfortune and evil spirits. In 1566, a fascinating purification ceremony called o-uma nagashi (お馬流し, literally “floating of the horses”) was started to do just that.

The horses of o-uma nagashi consisted of six handmade figures made of straw with heads resembling a horse and bodies resembling a turtle. Each of the six villages at Negishi created such a horse in summer. They were laid in boats that were set afloat with the outgoing tide in the belief that they would take disease, evil spirits and any other misfortune with them.

Therefore, if they came floating back, it was seen as a terrible omen. This apparently happened in the Summer of 1923 (Taisho 12), just weeks before one of Japan’s most destructive earthquakes in recorded history flattened Yokohama and nearby Tokyo. Disturbingly, all six horses came floating back.

The roots of o-uma nagashi are believed to reach back to the Kamakura Period (1192–1333). Samurai in those days kept their horses at the pastures of nearby Wadayama (和田山), present Konanku (港南区). It is theorized that they floated dead horses into the sea.1 Local legend had it that the area was haunted by an evil spirit which took over many of the horses. The ceremony was started to cleanse the area.

The Japanese of old usually managed to create fun out of the most serious ceremonies and at some time the ceremony was enlivened with an exciting boat race. A reduced version of o-uma nagashi still takes place today.

In 1864 (Bunkyu 4), a road was built from Yamate along Negishi. Ostensibly, to offer foreigners a safer route to travel. On September 14, 1862 four British subjects had been attacked by samurai near the village of Namamugi on the Tokaido, an event now known as the Namamugi Incident. One of them died. The incident threatened to turn into a full-blown diplomatic crisis and eventually resulted in the naval bombardment of Kagoshima by British vessels in 1862 (Bunkyu 2).

The road turned the area into an oasis the foreigners gladly escaped to. They would come here to have pick-nicks or watch the horse races that were held at the Negishi race track. The beauty of the place managed to survive until the 1960’s, when bureaucrats and businessmen decided to fill up the beautiful tidal flatlands and create a huge industrial zone.

Where once mothers and their children searched for shellfish is now a huge highway, and where the fishermen pulled in their nets are tanks filled with the fuel that runs our modern world. Factories, refineries and smokestacks fill up the rest. From Yokohama to Kanazawa, an entire coastline and its natural habitat has been thoroughly destroyed. A place of unspeakable beauty that took millions of years to take shape has been sacrificed on the altar of greed.

It is a scene that has been countlessly repeated along most of Japan’s Pacific coast and continues to this very day, as the destruction of the tidal flats in Isahaya Bay in Nagasaki Prefecture so tragically showed.2

The average Japanese is as much to blame as the planners. Many still think parochially and believe that an event in another town or prefecture does not affect them. It is too far away. But what happens in one place does affect the whole of the country. It sets an example and precedent that will be copied and repeated over and over again.

This is exactly what has happened with the destruction of Japan’s natural environment. There is no far away anymore, it has reached just about everybody. An increasing number of people now realize that when you destroy natural habitat and animals on this scale, you eventually destroy human life. But will enough people realize this in time? And will enough of them act?

Kunio Francis Tanabe, a former senior editor with The Washington Post, grew up in the Honmoku area in the 1940’s and 1950’s. In 1999, he returned for a short visit and recalled his childhood in this pristine area in an article in The Japan Times3:

Fishermen ruled the neighborhood, strutting about in their loincloths and “hachimaki” (rolled cotton bands around their sunburned heads), showing off their elaborate tattoos of sea dragons and other fantastic creatures. They spoke a distinctive dialect common among fishermen of the bay and the Shonan beaches. This language is full of irony and exaggeration: For example, something tiny would be “dekkakahneh” or “How large it is!” Something large would be the opposite, “chitchakahneh.” On New Year’s Day, the fishermen showered us children with coins and candy; they organized the Ouma Nagashi ceremony and the Bon Odori; and they collected funds for the local Shinto shrine. They blew conch shells to signal a big catch, foretold the coming of storms and the red tide and organized evacuations during a terrible typhoon. They also taught us how to spear fish, harvest seaweed for “nori” and trap crabs. If a sea turtle got tangled in their nets, they would offer sake and take it back to the deep water to set it free — all the while praying for a good catch. “Asari,” “aoyagi” and “hamaguri” shellfish were plentiful. Sand dollars and sea cucumbers appeared everywhere at low tide. We learned to step on “karei” flatfish (usually accidentally, since they are well-camouflaged) and grab them with our bare hands. We would take out our boats and go spearfishing or cast fishing lines even in the cold months. In warm weather, fishermen and their wives would mend their large nets. Perhaps they could hear my grandmother playing her harp, the exotic music harmonizing with the sound of waves.

Notes

1 タイムスリップよこはま。お馬流し. Retrieved on 2008-07-28.

2 The Mainichi, July 31, 2018. High court ruling on Isahaya Bay floodgates highlights national gov’t brazenness. Retrieved on 2021-08-22. Replaced the irrecoverable link: The Asahi Shimbun, June 30, 2008. EDITORIAL: Ruling on Isahaya Bay. Retrieved on 2008-07-27.

3 Tanabe, Kuni Francis (1999).Memories of old Honmoku. The Japan Times. Retrieved on 2008-07-27.

4 If you want to attend o-uma nagashi, contact Honmoku Jinja (本牧神社) at 045-621-7611 to make sure of the dates (early August).

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Yokohama 1880s: Farms at Negishi, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/309/farms-at-negishi

Umlud

I really like this post. I used to live on the Yokohama-Tokyo border area and it was – also – getting gobbled up on both sides by the cities. The parochial viewpoint at that time even extended to waste disposal. Never had I seen such a disconnect between personal actions and larger impacts. (Even as a 3rd grader at the time, I understood this thing.)

#000346 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

I guess that the larger the number of people, the bigger the disconnect. The trick lies surely in the ability to organize to combine the personal actions of so many people that they can’t be ignored anymore. The internet now makes this possible, but, I wonder, are people wired for it?

#000347 ·

Kunio Francis Tanabe

Lovely photographs of old Negishi. Thank you for linking the Negishi photographs and a photo of the “oumanagashi” with the story I wrote of Honmoku for The Japan Times. There is a woodblock of the Honmoku coastline by the great Hokusai, “Gathering Shellfish at Ebbtide (ca. 1806-11). The Osaka Museum of Art owns a copy (shown in Washington D.C. at the Hokusai exhibit (Freer/Sackler gallery).

#000375 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

Thanks, Kunio. I am glad you liked it. I really enjoyed reading your article and was very happy that I could help keeping some of your memories of how Negishi used to be alive.

#000376 ·

Eric Davis

Our address in Yokohama was 91 Sannotani, just up the street from the Sannotani streetcar stop and a half hour walk to San Kaien Gardens.

We lived in Japan 1951-1961.

#000623 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

Hi Eric,

Fascinating. Do you still have photographs of Yokohama of that period?

#000624 ·

Charles A Samson

Thank you so much for the wonderful photos and text about Negishi. My grandmother was born in Yokohama in 1909, and she lived at 3369 Negishi-machi. Apparently, this was the road to Negishi and was opposite the Bluffs where she went to school at St. Maur’s. Their home was destroyed in the 1923 Great Kanto earthquake and they left Japan. I have tried to figure out where 3369 Negishi-machi might be today, without any luck. If you can identify it, I would be very grateful!

#000666 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

@Charles: Thank you for sharing your family history in Yokohama. I had a look at some old maps, but could find no information for 3369 Negishi-machi… Unfortunately, Yokohama maps are a bit rare. Possibly because of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923.

#000667 ·