Japanese silk cocoon traders weighing cocoons in the 1900s. Ordinary people like these men, most of them in Japan’s rural heartland, quietly turned the country into the world’s leading exporter of raw silk.

Introduction

When this scene was photographed, silk was one of Japan’s most important industries. The country became the world’s leading exporter of raw silk in 1909 (Meiji 42), around the time these men posed for this photo.

By 1929 (Showa 4), 10% of Japan’s limited farmland was devoted to mulberry trees, whose leaves fed the silkworms producing silk.1 Raw silk and silk products made up roughly 40% of Japan’s total exports. Moreover, an astounding 90% of the silk imported into the United States came from Japan.2

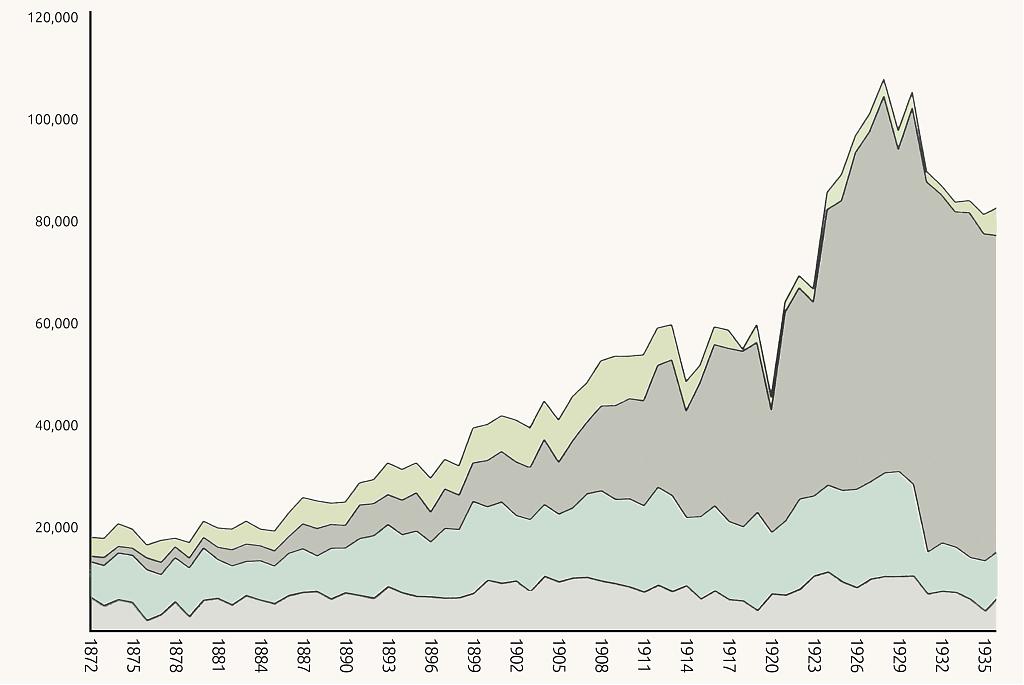

The graph below illustrates the growth in Japan’s silk production and exports from 1872 (Meiji 5) to 1936 (Showa 11). From the 1910s, Japan (the darkest color) dominated the global silk industry, dwarfing exports from Italy (at the bottom), China (above Italy), and other countries.3

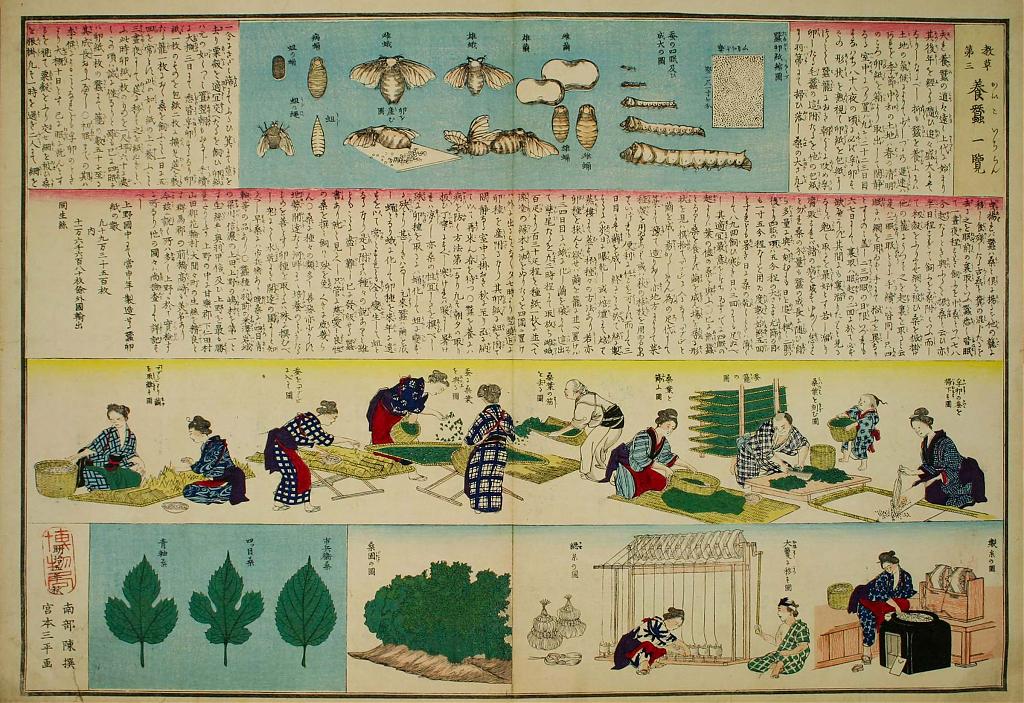

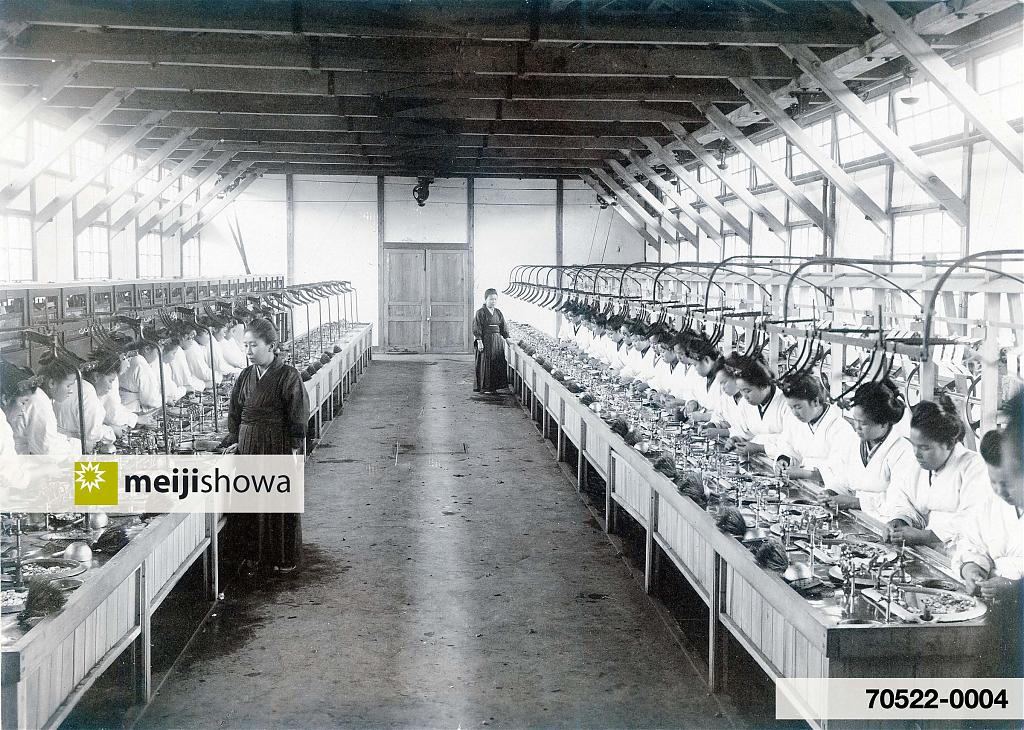

Since the Meiji Period (1868-1912), silk reeling increasingly shifted to factories, replacing much of the home-based spinning done by farm women.

However, silk cocoons continued to be produced on small family farms, generally by households struggling to make ends meet on agriculture alone. Cocoon production was a side business, filling the months between harvests.4 As a result, the average mulberry area per farm was a mere third of a hectare (0.75 acre), less than half a professional soccer field.5

Although a side business for many farmers, silk was incredibly important. By the late 1920s, nearly 2.2 million families, an astonishing 40% of Japanese farm households, were involved in producing silk cocoons. Most of them raised the silkworms right inside their homes, using part of their living space for the task.6

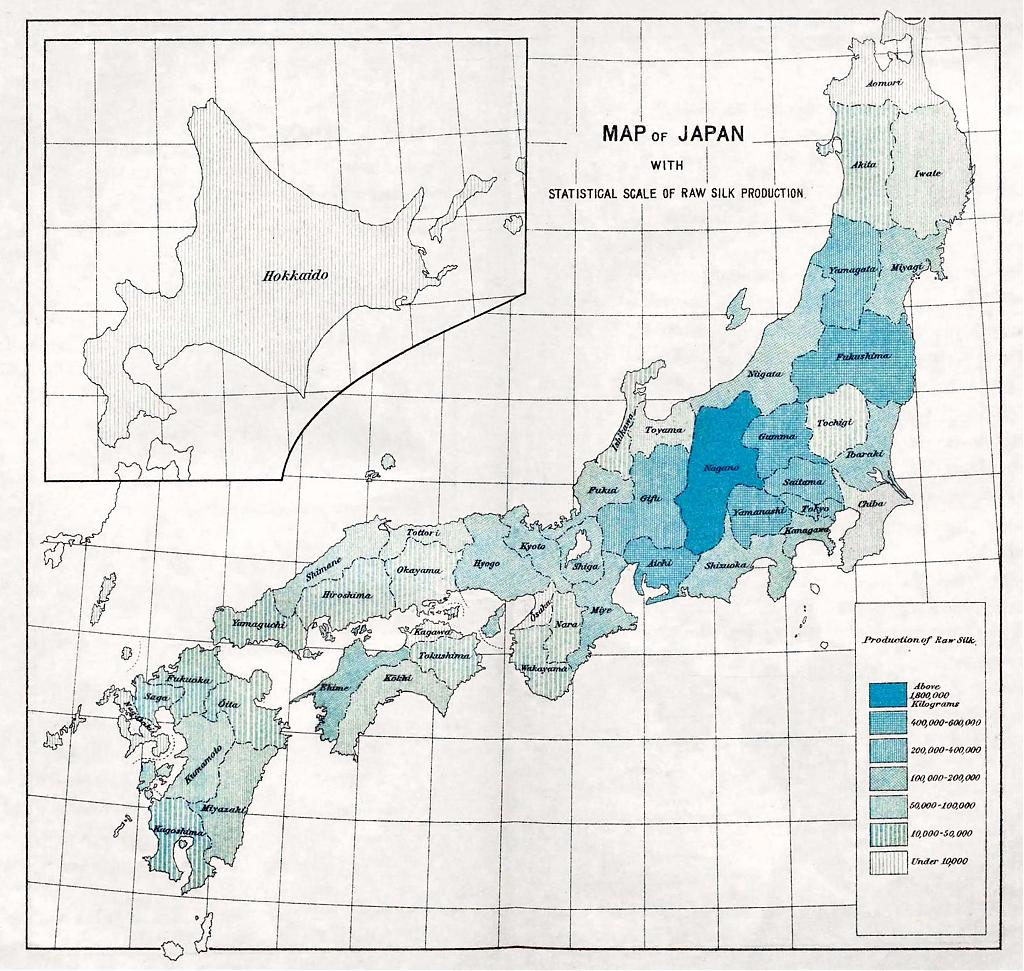

Silk production took place across the country, but especially in central and eastern Japan, notably in Nagano. This is clearly visible on this 1909 (Meiji 42) map from the Imperial Tokyo Sericultural Institute showing raw silk output by prefecture.7

On this map, Yamagata Prefecture in northeastern Japan appears among the third-ranked producers, producing between 200,000 and 400,000 kg versus over 1.8 million in Nagano. British travel writer Isabella Bird (1831-1904) journeyed through Yamagata in 1878 (Meiji 11), the first foreigner most locals had ever seen. While staying in what is now Kawanishi, she noted that silk ruled the area:8

Silk is everywhere; silk occupies the best rooms of all the houses; silk is the topic of everybody’s talk; the region seems to live by silk. One has to walk warily in many villages lest one should crush the cocoons which are exposed upon mats, and look so temptingly like almond comfits.

The Roots of Success

In the past, when Japanese companies competed with their Western counterparts, observers in Europe and the United States often attributed Japan’s success to low wages. This view was especially strong in the silk industry. Its public image was one of poor farm families raising silkworms in small thatched homes, and young rural women working long hours in factories for meager pay. Photos introducing the silk industry as a rustic cottage industry reinforced this image.

In reality, the story was far more complex. In 1929 (Showa 4), Charu Chandra Ghosh, an entomologist with the government of the British crown colony of Burma, today known as Myanmar, spent five months in Japan studying its silk industry. In his landmark study, he offered the following explanation for Japan’s remarkable success:9

Japan has been able to build up this huge industry principally because she has been spending about Yen 11,000,000 every year for research, experiment, propaganda and subsidy. This amount does not include the expenditure on sericultural education in schools and the four universities.

When Ghosh wrote this, Japan had already made the silk industry a national priority for more than sixty years. After the Meiji government came to power in 1868, it was guided by the rallying cry Fukoku Kyōhei (富国強兵), “Enrich the country, Strengthen the armed forces.” It zealously pursued industrial growth and the development of export markets to earn the foreign currency to finance that growth. Silk became the primary vehicle for achieving this. Later, cotton played an important role too, but silk remained king.

Japan kickstarted the process by spreading advanced techniques and building model factories. Particularly important was the Tomioka Silk Mill completed in 1872 (Meiji 5). This state-of-the-art facility introduced steam-powered reeling and modern factory systems. The nation even turned to symbolism. In 1871 (Meiji 4), Empress Shōken (1849–1914) began raising silkworms within the Imperial Palace grounds, a practice that continues today.10

Japan increasingly promoted progress through research, experimentation, and rigorous quality control. By the late 1920s, 343 controlling stations (蚕業取締所, sangyō torishimarijō) and 77 sericultural experiment stations (蚕業試験場, sangyō shikenjō) operated across the country. The principal experiment station in Nakano, Tokyo, employed an impressive 400 people.11

This approach proved successful. Amongst many other accomplishments, researchers at these institutions developed a superior silkworm strain, which quickly spread across the country during the 1910s. This effectively standardized silk production, resulting in increased productivity. It enabled farmers to supply high-quality cocoons at lower cost than foreign competitors, while reelers produced more uniform raw silk.12

Sericulture education was equally influential. Some 241 sericultural, agricultural, and other middle schools offered courses in silk production. There were three dedicated sericultural colleges, and four universities taught regular courses in sericulture. Even the six-year compulsory primary curriculum introduced children to the silkworm.13

Two national silk associations further promoted improvements in trade, sericulture techniques, mulberry cultivation, silkworm rearing, and cocoon production.14

Taken together, these efforts helped make Japan’s silk-reeling industry one of the most technologically advanced in the world by the 1920s and 1930s.15

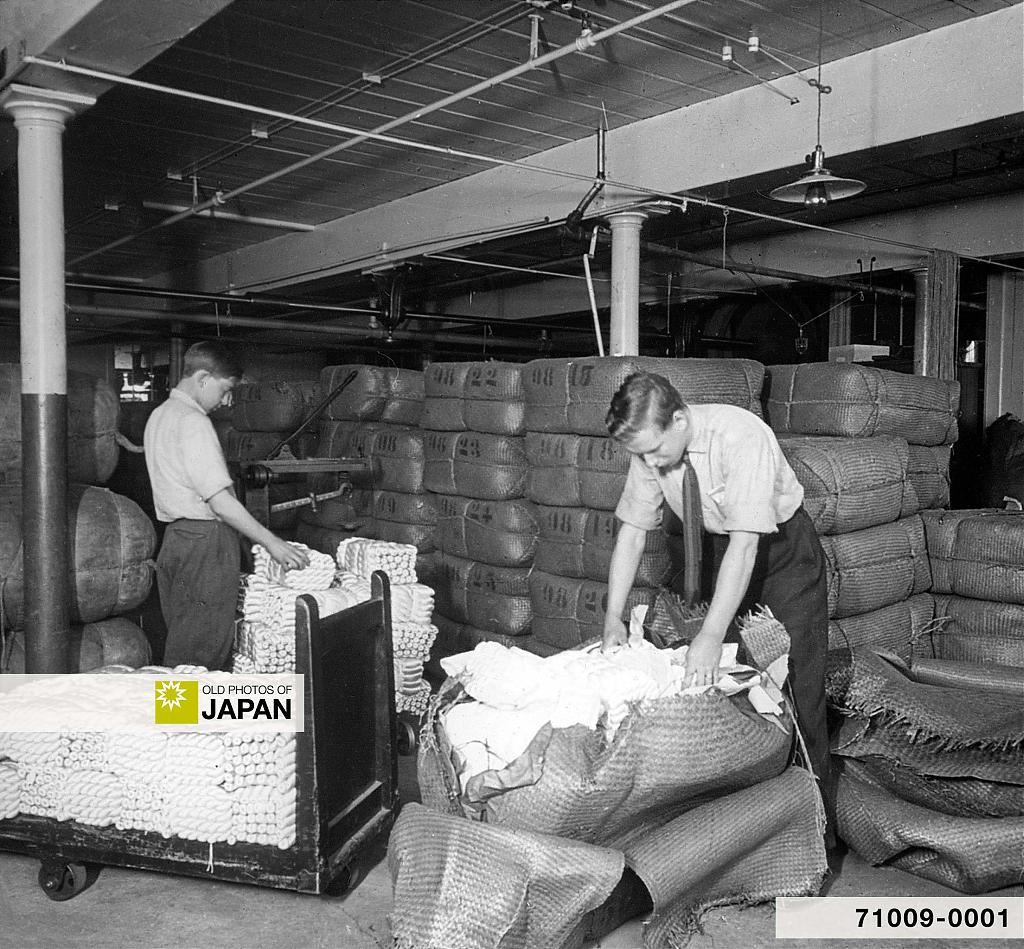

Surprisingly, the United States played a key role in this success. By the 1920s, it consumed half of the world’s exportable raw silk, 90% of it from Japan, making it the nation’s most important customer. To meet this vast demand for high-quality and uniform silk suited to modern machinery, Japan improved production and testing methods continually.

The two nations were effectively moving forward together, each influencing the other’s progress. In a sense, like dance partners holding hands.

'The Silk Industry of Japan'

The following two articles introduce a relatively rare 1920s photo book that offers an intimate look at silk farmers raising silkworms. With helpful notations for context!

Notes

1 Ghosh, Charu Chandra (1933). The Silk Industry of Japan with Notes on Observations in the United States of America, England, France and Italy. Delhi: The Imperial Council of Agricultural Research, Manager of Publications, 4.

2 ibid, 1.

3 Ma, Debin. (1996). The Modern Silk Road: The Global Raw-Silk Market, 1850-1930. The Journal of Economic History, 56(2), 340.

4 Schaal, Sandra; Smith, Jim (2022). Discovering Women’s Voices. Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 29–30.

5 Ghosh, Charu Chandra (1933). The Silk Industry of Japan with Notes on Observations in the United States of America, England, France and Italy. Delhi: The Imperial Council of Agricultural Research, Manager of Publications, 5.

6 ibid, 4.

Also: Honda, Iwajirō (1909). The Silk Industry of Japan. Tokyo: The Imperial Tokyo Sericultural Institute, 81.

7 Honda, Iwajirō (1909). The Silk Industry of Japan. Tokyo: The Imperial Tokyo Sericultural Institute, 12–13.

8 Bird, Isabella L. (1881). Unbeaten Tracks in Japan: an Account of Travels on Horseback in the Interior, Including Visits to the Aborigines of Yezo and the Shrine of Nikkō. Vol. 1. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 264.

9 Ghosh, Charu Chandra (1933). The Silk Industry of Japan with Notes on Observations in the United States of America, England, France and Italy. Delhi: The Imperial Council of Agricultural Research, Manager of Publications, 8.

To put the 11 million yen for “research, experimentation, publicity, and subsidies” in perspective, the average silk farmer earned just 253 yen in 1928–1929. Ghosh, 5.

10 The public relations office of the Government of Japan has a detailed video clip about Japan’s empress raising silk.

11 Ghosh, Charu Chandra (1933). The Silk Industry of Japan with Notes on Observations in the United States of America, England, France and Italy. Delhi: The Imperial Council of Agricultural Research, Manager of Publications, 5, 6, 74.

12 Ma, Debin. (1996). The Modern Silk Road: The Global Raw-Silk Market, 1850-1930. The Journal of Economic History, 56(2), 341.

13 Ghosh, Charu Chandra (1933). The Silk Industry of Japan with Notes on Observations in the United States of America, England, France and Italy. Delhi: The Imperial Council of Agricultural Research, Manager of Publications, 7.

14 ibid, 8.

15 Ma, Debin. (1996). The Modern Silk Road: The Global Raw-Silk Market, 1850-1930. The Journal of Economic History, 56(2), 342.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Inside 1900s: The Quiet Power of Japanese Silk, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/984/economic-power-of-japanese-silk-1900s

There are currently no comments on this article.