PART 1 | PART 2

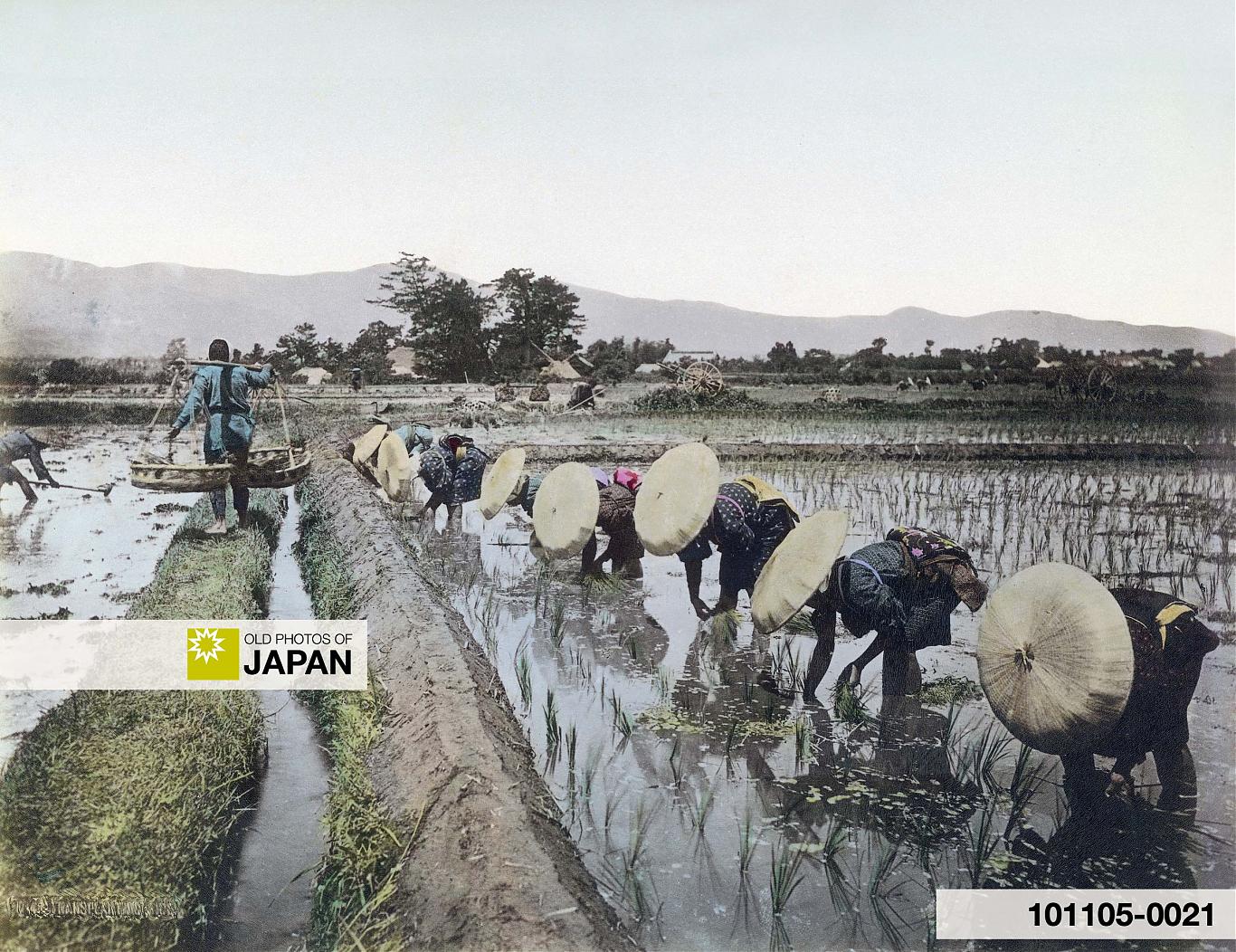

Japanese women transplanting rice seedlings, a process called taue (田植え). Rice farming was hard backbreaking work. For small farmers it was barely worth the effort. Education, innovation, and fertilizer aimed to change that.

This site is funded by readers like you

Old Photos of Japan provides thoroughly researched essays and rare images of daily life in old Japan free of charge and advertising. Most images have been acquired, scanned, and conserved to protect them for future generations.

I rely on readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support this work.

Introduction

This is Part 2 of an essay about Japan’s green revolution during the Meiji Period (1868–1912). By the 1930s, Japan had doubled the output of six major staples and ranked fifth globally in per-acre fertilizer consumption.

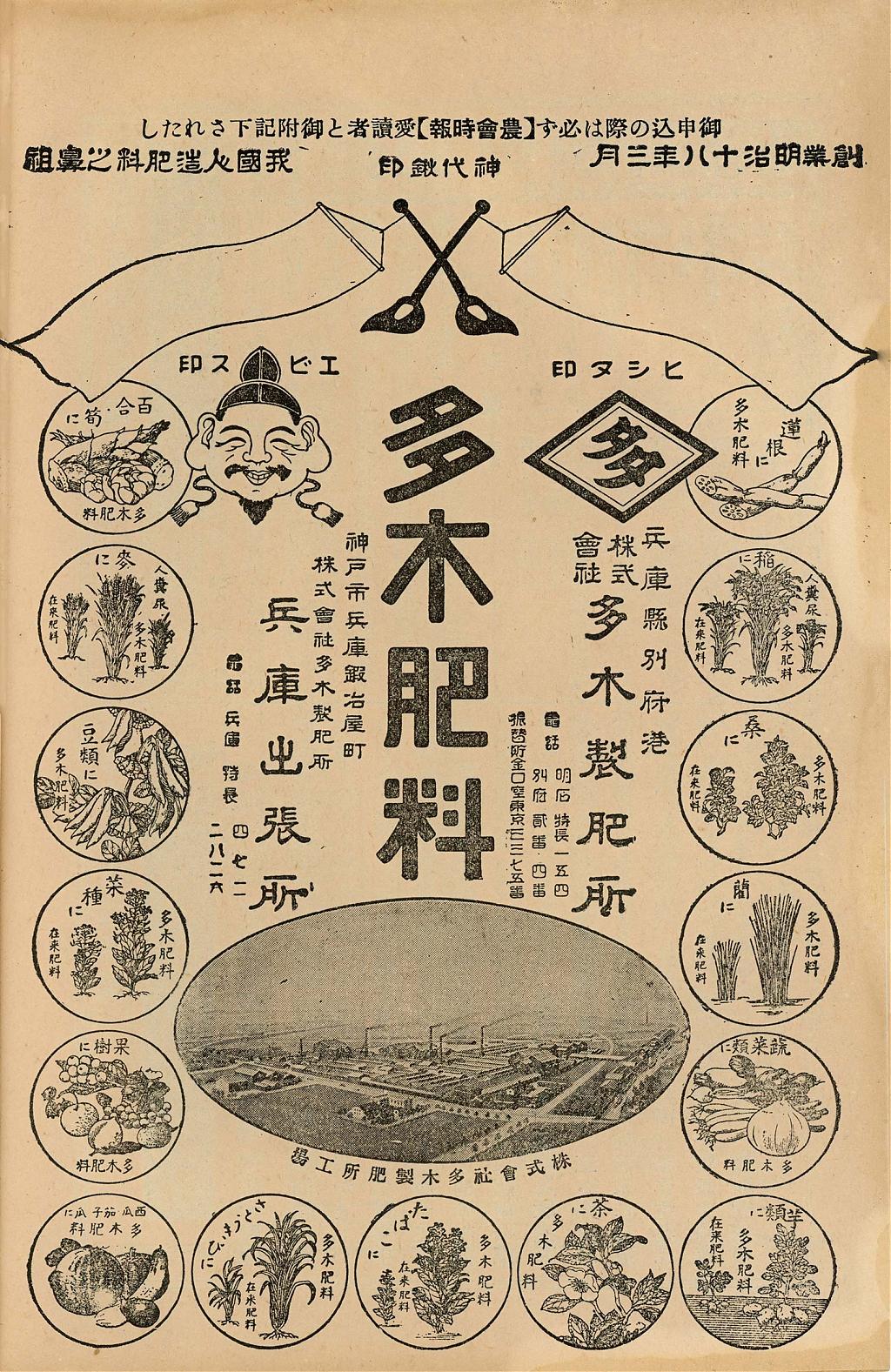

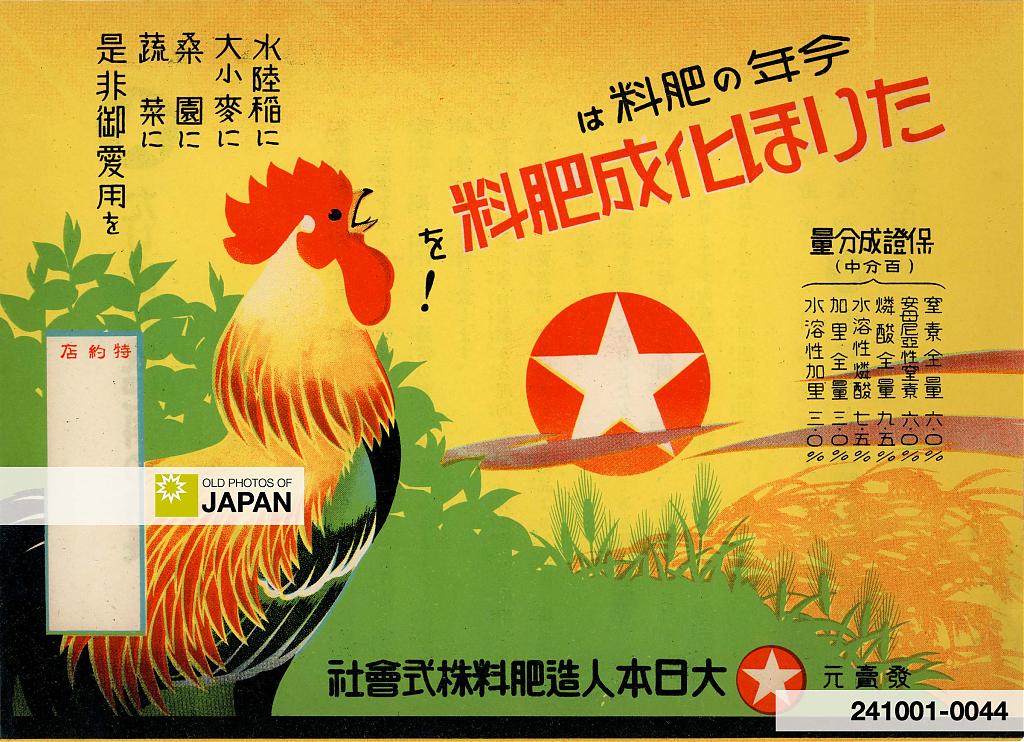

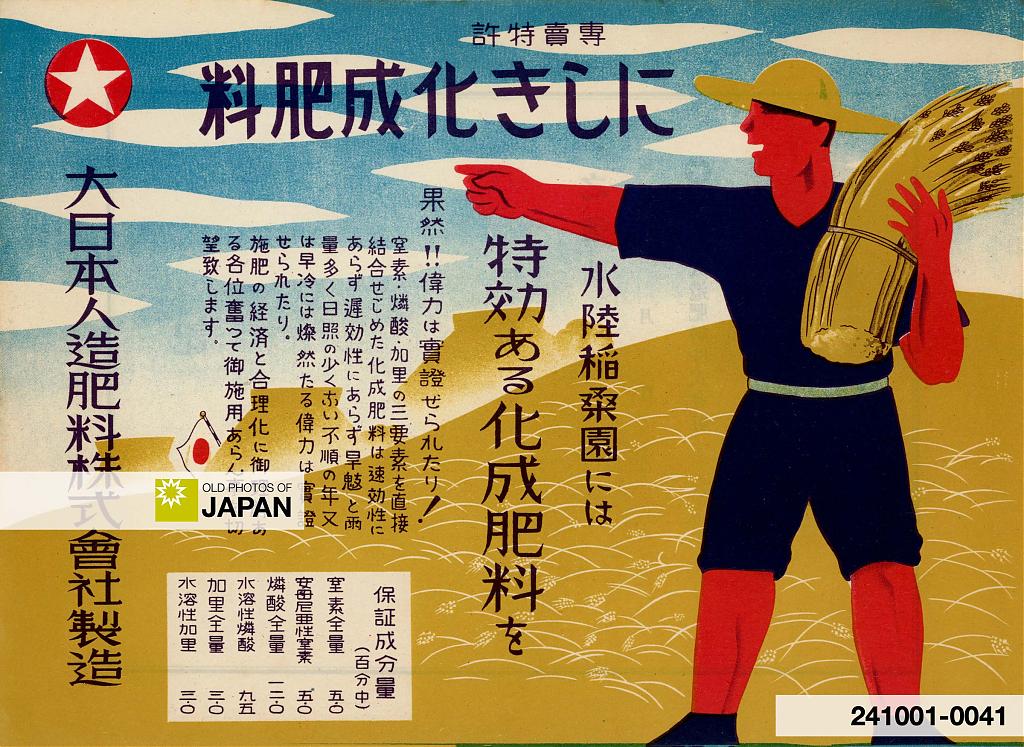

Part 1 briefly introduced the fascinating founders of the Dai-Nippon Artificial Fertilizer Company, a major force behind Japanese farmers’ staggering increase in the use of commercial fertilizers.

It also looked at the greatest hurdle that artificial fertilizer companies had to overcome: the lack of efficient distribution systems. Much of rural Japan was still remarkably remote and isolated, especially on the Japan Sea side of the country.

This article delves into the most sobering part of the story: many Japanese farmers were struggling and couldn’t afford fertilizers.

Barely Surviving

Japanese farmers had always struggled to eke out a living, but life grew even harder after the newly installed Meiji government introduced a burdensome land tax that forced many to sell their land and rent it instead. In 1873 (Meiji 6), when the new system of taxation and private land ownership was first introduced, tenant farmers cultivated 27.4 percent of Japan’s farmland. By the 1890s, that share had climbed to more than 40 percent.10

Whether they were owned or rented, the great majority of Japan’s farms were tiny, an average size of 1 ha (2.47 acres) per household. Industrialization in Europe and the United States led to fewer but larger farms. However, even as industry expanded during the Meiji Period (1868–1912), Japan remained a nation of small-scale family farms. Unsurprisingly, many farmers struggled to make ends meet on their small plots.

Life became particularly difficult in the 1880s. To curb Japan’s rampant inflation, Finance Minister Masayoshi Matsukata (松方正義, 1835–1924) imposed harsh fiscal reforms, including heavy taxation and drastic government spending cuts. The currency stabilized and government finances recovered, but agricultural prices plummeted, bringing unimaginable hardship to rural areas. For many farmers artificial fertilizer was a luxury far beyond reach.

In his autobiographical novel The Soil (1910), poet and novelist Takashi Nagatsuka (長塚節, 1879–1915) describes the plight of such struggling tenant farmers:11

Kanji’s fields yielded a pitifully small harvest that fall. It was not that the weather had been bad or that the soil itself was poor. He had got his crops in late and had not applied much fertilizer. No matter how much energy he expended the results were bound to be disappointing. It was the same for all poor farmers. They spent long hours in their fields doing all they could to raise enough food. Then after the harvest they had to part with most of what they had produced. Their crops were theirs only for as long as they stood rooted in the soil. Once the farmers had paid the rents they owed they were lucky to have enough left over to sustain them through the winter. During the growing season itself they had to abandon their own fields to do day labor for others to earn money for that day’s food. They had not forgotten that their own fields needed tending—in a village where everyone worked at farming it was impossible to forget what needed to be done at any given time. They simply had to deal with the immediate necessity of getting something to eat. Even when their own crops most needed attention they might not be able to provide it for days at a time. Nor could they do much about fertilizer. It was no longer possible to obtain free compost from the forests as they had always done in the past. Now the forests were privately owned, and one had to pay to collect leaves or cut green grass. Where people had been at work with their rakes every winter the grass had become stunted, and where the grass itself had been cut the soil gradually deteriorated. Without money one could not obtain good, soft grass at all anymore, unless of course one stole it. Only after others had been through the forests with their rakes and sickles could poor farmers enter to scavenge for leaves and grass. Then they scratched away at the already impoverished soil, leaving it even more exposed and infertile than before. As the forests became depleted, all sorts of artificial fertilizers appeared in the countryside. But once again only those with money could make use of them. Poor farmers were caught up in a vicious circle. Lacking fertilizer they were unable to grow much more than they owed their landlords in rents. So they had to find other work in order to obtain the food they needed. But when they found such work they fell behind in weeding and cultivating their own fields. If they missed even a few days during the hot, wet summer the weeds would shoot up and stifle the growth of their crops. That alone was sufficient to reduce yields. It was just as if they had uprooted the crops before they had matured and eaten them.

Going Artificial

To make things even more challenging for artificial fertilizer producers, many farmers who could afford to buy their product were wary of it. They preferred organic fertilizers.

A significant breakthrough came when researchers at Tokyo University mixed superphosphate with materials farmers were already using, such as herring, rice bran, and night soil (human excrement). The mixture with night soil proved especially effective because it narrowed the psychological gap between old and new methods — farmers had used organic night soil mixtures for centuries.12

The shift to artificial fertilizers was also driven by circumstances. The First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895) disrupted imports of popular soybean-cake fertilizer from China. Simultaneously, unusually poor fish catches in Hokkaido cut supplies of fish-based fertilizer.

Farmers now faced a stark choice: accept smaller harvests or try alternatives. Naturally, many tried the alternative. As adoption of artificial fertilizers spread, production grew and prices fell, further reducing resistance. After years of sluggish growth, sales surged.13

| Year | Sales | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1888 | 184 | Tokyo Artificial Fertilizer starts operations. |

| 1889 | 465 | |

| 1890 | 390 | |

| 1891 | 1,560 | |

| 1892 | 1,853 | |

| 1893 | 1,571 | |

| 1894 | 3,176 | First Sino-Japanese War |

| 1895 | 4,013 | First Sino-Japanese War |

| 1896 | 7,013 | |

| 1897 | 11,096 | |

| 1898 | 16,395 |

Other initiatives, first launched at the dawn of the Meiji Period (1868–1912), did even more to encourage the use of artificial fertilizers. Ironically, these efforts grew out of Japan’s drive for industrial progress, one of the Meiji government’s chief policy goals.

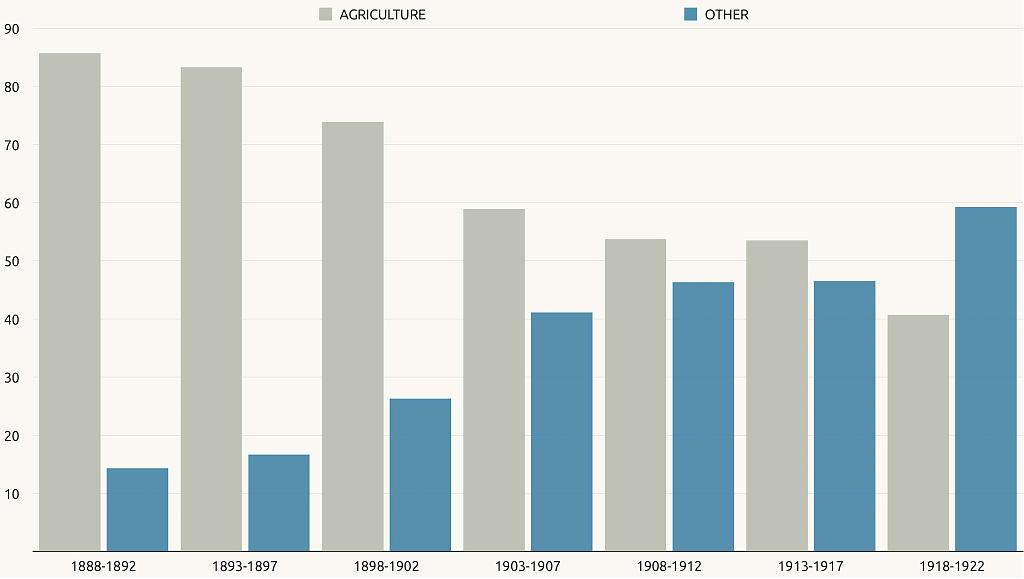

During the first three decades of the Meiji Period, Japan’s economy still rested squarely on the shoulders of its farmers. As late as 1900 (Meiji 33), nearly all of the nation’s tax revenue came from agriculture, an incredible 85.7% between 1888 and 1892. The graph below dramatically illustrates this dependence. The grey bars show the percentage of taxes derived from agriculture.14

When the government shifted its focus to industrialization, it relied on farmers to help fund the effort. Yet with nearly every patch of Japan’s arable land already under cultivation, there was only one way to raise additional revenue: increase the productivity of the fields.

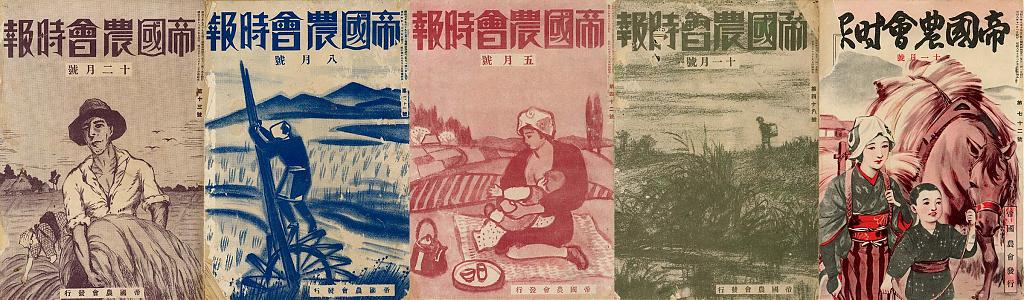

Reluctant to provide direct financial support, government officials instead chose indirect forms of aid. Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce launched educational campaigns to encourage the use of chemical fertilizers. It ran newspaper ads, handed out pamphlets, and sent agricultural college graduates into rural areas to teach new fertilization methods.

Experts encouraged farmers to breed new strains of rice that responded well to fertilizer. Because higher yields meant more income, many farmers expanded the effort, also improving other crops and refining farming techniques.15

Many worked closely with government experiment stations and agricultural improvement societies, launched to spread new techniques. In 1905 (Meiji 38), membership in these societies became compulsory, strengthening ties between farmers and researchers and accelerating the spread of innovation.16

Individual farmers were crucial to this innovation. As late as 1945 (Showa 20), seventeen rice varieties developed by farmers were still in cultivation. The most prominent one was grown on about 10 percent of the total rice area.17

This progress was possible largely because of the expansion of rural education during the Meiji Period, which gave farmers the capabilities, knowledge, and confidence to seek out information and experiment with new practices and technologies.18

The fusion of education, innovation, and fertilizer produced extraordinary results. Between 1880 and 1930, farmers doubled the output of the country’s six major staples: rice, wheat, naked barley, barley, sweet potatoes, and white potatoes.

Remarkably, they achieved this with only an 18% increase in cropland. Most of the gains came from higher yields, growing more from the same soil.19 It helped fund Japan’s industrialization and feed its booming population. But it came at the steep cost of sweeping away centuries of sustainable, closed-loop recycling practices.

Related Articles

Notes

10 Francks, Penelope (2006). Rural Economic Development in Japan from the Nineteenth Century to the Pacific War. New York: Routledge, 47.

11 Nagatsuka, Takashi; Waswo, Ann (1989). The Soil: a Portrait of Rural Life in Meiji Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press, 47–48.

12 Molony, Barbara (1990). Technology and Investment: The Prewar Japanese Chemical Industry. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 27–28.

13 ibid, 31.

14 Johnston, Bruce F. (1962). Agricultural Development and Economic Transformation: A Comparative Study of the Japanese Experience. Food Research Institute Studies, Stanford University, Food Research Institute, vol. 3(3), 239–240.

“Expansion of the capitalist sector was, of course, facilitated by the light tax burden on industry made possible by the disproportionate tax load imposed on agriculture. During the period before 1920 the burden of direct taxes on agriculture ranged between 12 per cent of the net income of agriculture during the years 1913-17 to 22 per cent in the period 1884-87. By contrast, it is estimated that the burden of direct taxes on nonagriculture was only about 3 per cent of the net income of the secondary and tertiary sectors at the turn of the century (1898-1902) and reached a peak of 6 per cent in 1908-12.”

15 Molony, Barbara (1990). Technology and Investment: The Prewar Japanese Chemical Industry. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 19.

16 Johnston, Bruce F. (1962). Agricultural Development and Economic Transformation: A Comparative Study of the Japanese Experience. Food Research Institute Studies, Stanford University, Food Research Institute, vol. 3(3), 229.

“Other factors also contributed significantly to the increase of crop yields. Various improvements in farm practices—seedbed preparation, transplanting techniques, weeding, the timing and density of planting, timing and placement of fertilizer applications—made their contribution. Without such improvements in farming techniques, the full potential of higher levels of soil fertility and superior varieties could not have been realized. There was also progress throughout the period in extending irrigation systems and improving water storage and drainage. Their contribution to raising yields during the period under review should not be exaggerated, however, since irrigation of paddy fields was already highly developed by 1880. In addition to the work of plant breeders in developing disease-resistant varieties, a variety of other measures to control disease, fungus, and pest damage also played their part. Among the important control measures were the use of disease-free seed, the soaking of seed before planting, the roguing of diseased plants, the rotation of crops, and spraying or dusting with pesticides and fungicides.”

Also 234–235:

The government established an important agricultural experiment station in Tokyo’s Shinjuku as early as 1872 (Meiji 5). Other stations all around the country followed. In 1880 (Meiji 13) the Department of Agriculture and Commerce started promoting agricultural improvement societies. These received legal backing in 1899 (Meiji 32) and became compulsory for farmers to join in 1905 (Meiji 38).

17 ibid, 235.

18 ibid, 234–235.

19 ibid, 227.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Outside 1890s: Japan's Green Revolution (2), OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/983/farming-green-gevolution-in-meiji-japan-part-2

There are currently no comments on this article.