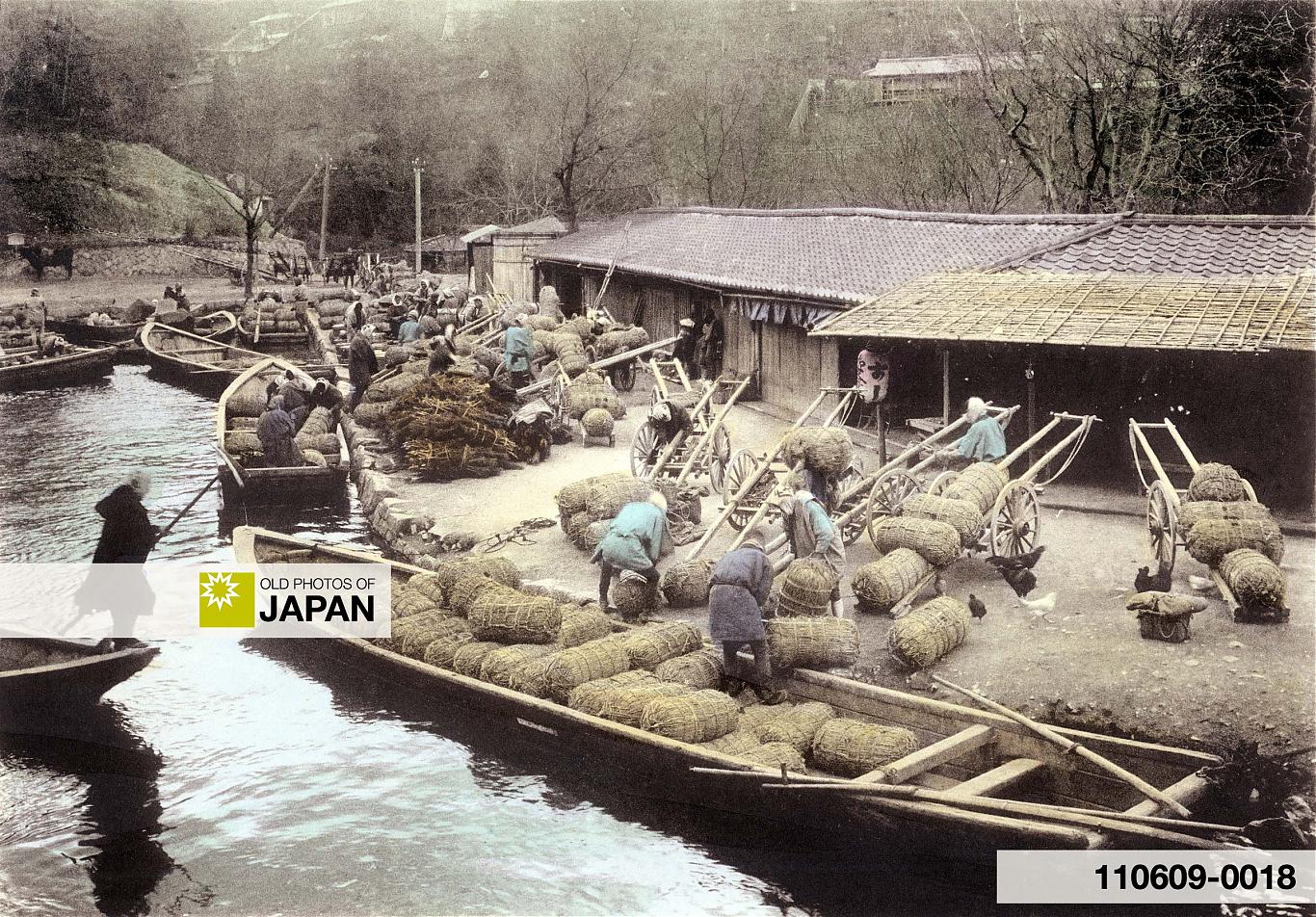

Laborers are loading bales of rice onto river barges. Photographer Teijiro Takagi published this scene in 1907 (Meiji 40) in a photo book about rice cultivation, The Rice in Japan. This article reproduces his book.

The collotype photos in The Rice in Japan introduce the steps involved in rice production in chronological order, and are accompanied by brief explanatory captions. The book therefore gives a fascinating view of rice culture in Japan in the early 20th century.

Most of the scenes, if not all, are almost certainly photographed in or near Kobe, where Takagi was based. I have been able to confirm one of the locations.

The book has been reproduced below with the original captions in italics, so that you can “hear” the story in the authentic voice of a contemporary observer. The titles, and non-italic explanatory notes, are mine.

1. Plowing

Plowing the field in preparation of the rice shoots.

2. Transplanting Rice Plants (March)

Early in March the seeds are thickly sown in marshy grounds; so soon as the plants are about five inches in height transplantation begins, and the young ‘Staff of Life’ is transferred to the field…

3. Planting (May)

Men and women, young men and maidens planting the rice. This takes place in May, and is a festive occasion; the girls are dressed in showy (working) garments, and they sing and joke in the midst of their labours. The scene depicted shows the toilers at work on a rainy day, hence the reason for the large, straw hats and straw ‘waterproofs’ they don for such occassions.

4. Irrigating

Irrigating the fields by means of the ancient foot water-mill. The ground needs constant weeding. The labourers posses an eagle for detecting rice worms, and manure is frequently applied to the ground/ We would advise anyone not to approach a rice fields [sic] very closely.

5. Growth

Trusting to good fortune, the farmers watch the crops thrive, and if all goes well the rice comes into ear about the end of October. Some terrible scarecrows are placed here and there, and they (to the terror of birds) perform uncanny postures as they swing about, attached to a yielding bamboo pole.

6. Harvest (November)

The harvest commences early in November if fine weather has resulted in fully ripening the crops. The ear at first is of a flesh colour, ripening into a rich brown tint.

I have found a photo very similar to the above one, where the location was given as Futaba in Kobe. This suggests that most, if not all, of these photos were photographed in or near Kobe.

Futaba-cho (二葉町) is now part of Nagata-ku (長田区), the heavily built up area that burned down after the Kobe Quake of 1995. Footage of the devastating fires in Nagata-ku dominated the news for days, and terrified everybody who survived the disaster. It is hard to imagine that just a century ago, the area was still this rural.

7. Drying

Temporarily stacking the rice on bamboo poles, in order that it may become thoroughly dry; this is one of the most important proceedings.

8. Hauling in the Rice

After some fine dry days have elapsed, the rice is conveyed to sheds…

9. Threshing

Thrashing out the grains, according to primitive methods.

Two farmers are threshing rice stalks with a senba koki (千歯扱き).1

10. Husking

Breaking the corn for the purpose of removing the husks.

The rice is dropped into a mill (土臼, do’usu)2 while three women push and pull the top of the milling stone with a large wooden handle. This was hard and mind-numbing work, so the farmers usually sang work songs, known as usu-hiki uta (臼ひき唄), to keep the rhythm and stay entertained.

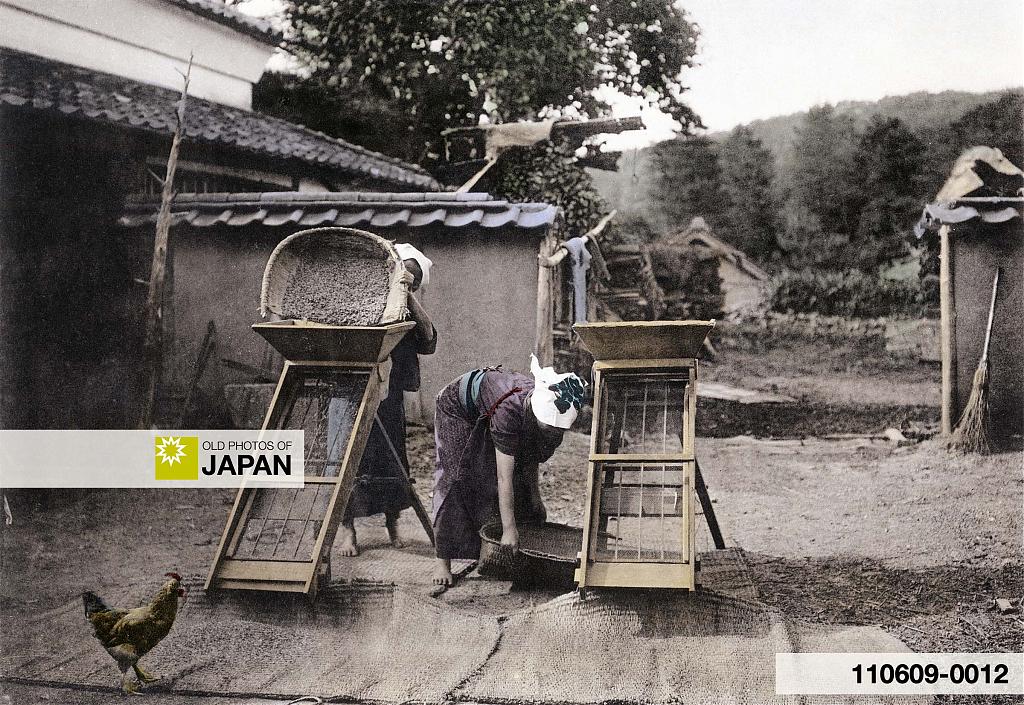

11. Winnowing

A shaking machine, by which the grains are sifted and the husks removed.

A farmer is using a winnowing machine (唐箕, tōmi).3 The process of separating the grain from the chaff was called fūsen (風選), and involved one person feeding the tōmi with grain, while another turned the fan. The wind did the rest. The machine could be adjusted to increase effectiveness.

Invented in China in the beginning of the Common Era, the tōmi was used in Japan extensively. Strangely, it reached Europe only in the 18th century.

12. More Winnowing

A further sifting is necessary to separate the unbroken corn from the fractured rice, and to remove sand, etc. The broken corn is also carefully extracted; the farmers leave no opportunity for gleaners.

13. Packing

Packing the precious material in straw bales.

If you have read a few history books about Japan, you will have encountered the term koku (石), a measurement of rice. Until the Meiji period, the size of a daimyo’s (feudal lord) estate, as well as income in general, was measured by koku.

You may have wondered how much exactly a koku was. It is easy to explain with rice bales (米俵, komedawara).

During the Edo period (1603–1867), the capacity of komedawara varied by region, but it was generally between two and five to (斗, about 18 liters). During the Meiji period (1868–1912), one komedawara was standardized as four to, so about 72 liters.4

Ten to made one koku. So, one koku was about two and a half rice bales.

Including the barely visible ones in the back, there are over 100 bales in the top photo with the river barges. This comes to at least 40 koku. To be a daimyo, a samurai needed an annual income of 10,000 or more koku, so some 250 times the number of bales in the top photo.

An income between 100 and 9,500 koku qualified one as a hatamoto (旗本, upper vassal of the Tokugawa house), while an income of less than 100 koku made one a gokenin (御家人, lower vassal).

Incidentally, in 1891 (Meiji 24), a koku was legally defined as 180.39 liters, or about 5.12 U.S. bushels.

14. Storage

Depositing the rice in the store-houses.

Notice that each person is carrying a komedawara on his shoulder. As explained above, that is about 72 liters, probably over 55 kilograms (121 lbs). These men are likely carrying more than their own body weight.

15. Transport

Removing the corn to be treated to another form of grinding to remove the bran.

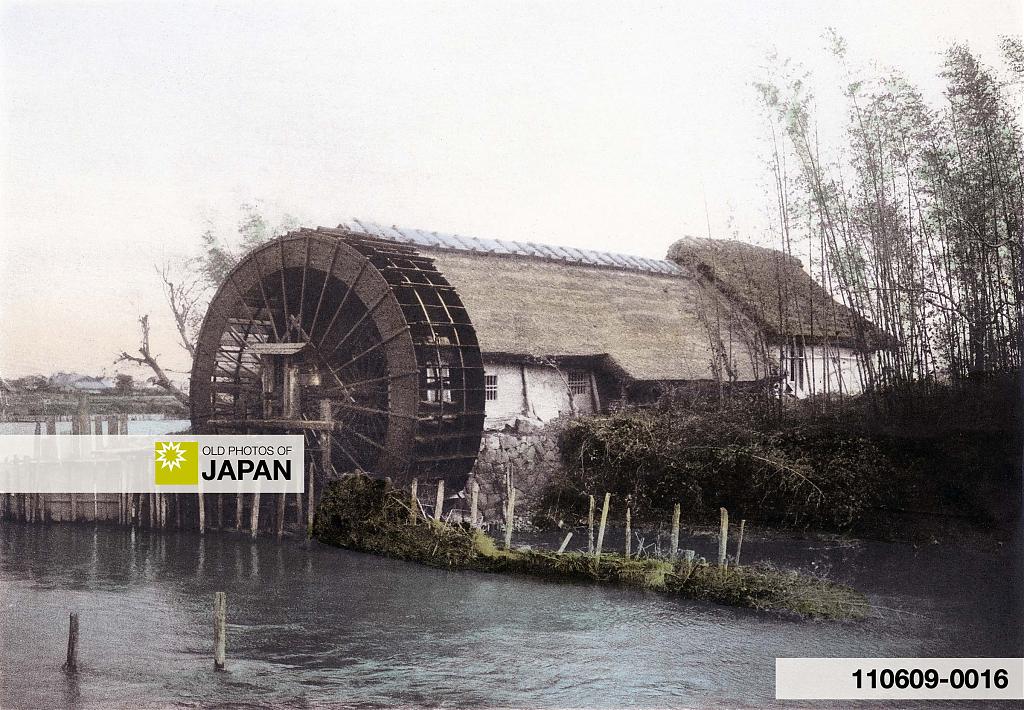

16. Watermill

A water-mill grinding the rice.

Inside the mill house, the rice is polished by a pestle and mortar. Gears lift the pestle. When it is lifted to a certain height, it escapes the gearwheel and drops down to pound the rice in the mortar.5

17. Polishing

A still more ancient method of grinding the corn.

This is an older method of polishing the rice. A farmer is using a large leg-powered pestle and mortar (唐臼, karausu) to remove the bran from the rice.

Depending on the degree of bran removal, the rice is classified as 5-bunzuki rice (五分づき米), 7-bunzuki rice (七分づき米), or white rice (白米, hakumai).5

18. Shipping

All ready for the markets. Loading the rice in barges for transportation.

These river barges were flat bottomed, and could be used in extremely shallow water.

19. Rice Shop

A rice retailing shop. One or more of these stablishments are to be found in almost every street throughout the country. Excepting the poorer classes, patrons do not carry away their purchases, the latter being delivered regularly, at stated periods, to the residences of patrons. As is seen from the photo above, there are many grades of qualities and prices, the latter ranging from 17 to 20 sen per bushel.

As you can see, it took enormous amounts of effort to put rice on the table. So, Japanese parents used to teach their children to eat every single grain of rice in their bowl.

This was an important life lesson, too. Do not let anything, not even a single grain of rice, go to waste.

Rice Consumption in Japan

We always think of traditional Japan as a rice culture. But this was not absolute. During the Meiji period, less than half of the areas in cultivation were devoted to rice. Other grains and produce made up more than half.

Here is the situation in 1878 (Meiji 11).6

| Crop | Area﹡ |

|---|---|

| Rice | 2,535.4 |

| Rye | 838.3 |

| Wheat | 369.5 |

| Barley | 608.3 |

| Soybeans | 441.6 |

| German Millet | 236.3 |

| Sweet Potatoes | 159.4 |

| Buckwheat | 155.9 |

| Deccan Grass | 108.5 |

| Lentils | 44.5 |

| Italian Millet | 25.5 |

| Potatoes | 9.5 |

| TOTAL | 5,532.7 |

﹡ Area in units of 1,000 chō (町), approx. 1,000 hectares or 2,470 acres.

Even more surprising is that although rice was produced by farmers, they ate less rice than people in urban areas.

According to an official survey of the Ministry of Education in 1877 (Meiji 10), farmers consumed an average of 0.76 koku of rice per year, while town people averaged 1.28, more than one and a half times as much.

All through the Meiji period, only half of the total grain consumption in rural areas consisted of rice. Farmers had to mix other grains with their rice.

Diets also varied by region. In southwest Japan, sweet potatoes and barley were common. In the east, it was millet, buckwheat, and Deccan grass. While in the mountains, chestnuts and horse chestnuts played an important role in the diet.

Rice was only the principal daily food in Akita, Niigata, Toyama, and Ishikawa prefectures.

During the Edo period, people ate even less rice. A person answering an 1879 questionnaire, wrote that “in the past one could count on one’s fingers the days in the year when farming families of the middle class or even above ate rice.”7

About the Photographer

Although Teijiro Takagi (高木庭次郎) was extremely productive and active for some two decades, surprisingly little is known about his life. So little that he has even been described as a phantom photographer (幻の写真家).8

Both his dates of birth and death are still unknown, although he was probably born some time between 1872 (Meiji 5) and 1877 (Meiji 10). His somewhat better known father Kichihei (高 木吉兵衛, ?–1882) was also a photographer.9

Takagi studied under Kozaburo Tamamura, and worked as the manager of Tamamura’s branch store in Kobe. He is first listed as the owner of this store in the Japan Directory of 1904 (Meiji 37), suggesting that he took the business over in the preceding year. He continued to use the Tamamura name until 1914 (Taisho 3).

According to research by Terry Bennett, the Takagi studio continued until at least 1929 (Showa 4), with locations in Kyoto and Kobe.2 An edition of The Tea in Japan, photographed by Takagi, shows 1927 (Showa 2) as the date of publication.

But research by Robert Oechsle has uncovered a notice published by Takagi successor Futaba Shokai that it took over Takagi’s business on March 4, 1924 (Taisho 13). The new owners were his former employees.10

Takagi published at least thirty photo books that introduced Japanese life and customs in English, all of them with hand-colored collotype prints like the ones featured in this article.

He also produced a very large number of glass lantern slides. These hand-colored slides are of extremely high quality, comparable to Nobukuni Enami’s work.

Below are some of the photo books published by Takagi, initially under the Tamamura brand name. The books marked with ✷ are in my collection.

| Year | Title |

|---|---|

| 1904 | Leaf From the Diary of a Young Lady |

| 1905 | The Ceremonies of a Japanese Marriage ✷ |

| 1905 | From Peace to Strife, An Incident of the Bushido Spirit |

| 1906 | The New Year in Japan ✷ |

| 1906 | The Festival of the Ages |

| 1906 | The Great Gion Matsuri |

| 1906 | The Fishermen's Life in Japan |

| 1906 | Views in the Land of the Rising Sun |

| 1906 | The Japanese Tea-House (The Social Restaurant) |

| 1907 | The School Life of Young Japan ✷ |

| 1907 | The Rice in Japan ✷ |

| 1907 | The Transformation of Mother Earth from Nature to Art (pottery making) |

| 1907 | The "Ceremonial Tea" Observance in Japan ✷ |

| 1907 | The Chrysanthemums in Japan |

| 1907 | In and Out of Kobe |

| 1908 | Snap-shots of out-door life in Japan |

| 1909 | A Wintry Tour Around Fujiyama |

| ca. 1909 | Artistic Japan |

| ca. 1909 | Picturesque Japan |

| 1910 | Girls' Pastimes in Japan |

| ca. 1910 | Japanese Views and Characters (three volume set) |

| ca. 1912 | Three Mischievous Children |

| 1913 | The Building in Japan |

| 1915 | The Silk in Japan |

| 1915 | Hills of Kobe |

| 1917 | The Fujiyama |

| 1918 | Military Accomplishments of Japan |

| ca. 1918 | Views of Kioto |

| ca. 1919 | Famous Scenes in Japan |

| 1920 | Characteristic Gardens in Japan |

Notes

1 For Earth, For Life. Kubota. 時代とともに変化した「脱穀(だっこく)」するための道具 Retrieved on 2022-03-07.

2 For Earth, For Life. Kubota. 臼を使った「籾摺り(もみすり)」 Retrieved on 2022-03-07.

3 For Earth, For Life. Kubota. さまざまな道具を駆使した「籾(もみ)の選別」 Retrieved on 2022-03-07.

4 コトバンク。日本大百科全書(ニッポニカ)「俵」の解説 Retrieved on 2022-03-07.

5 For Earth, For Life. Kubota. 玄米をついて糠(ぬか)を取り除く「精米」 Retrieved on 2022-03-07.

6 Shibusawa, Keizo, Terry, Charles S. (1969). Japanese Culture in the Meiji Era, Volume V: Life and Culture. Tokyo: The Tokyo Bunko, 51.

7 ibid, 52–57.

8 石田哲朗(2015)。高木庭次郎の幻灯写真:収蔵作品《日本風景風俗100選》について。東京都写真美術館、101–102.

9 Bennett, Terry (2006). Photography in Japan 1853–1912. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 294–195.

10 Baxley, George C. Color Collotype Books by Tamamura & Takagi, Kobe. Retrieved on 2022-03-07.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 1907: "The Rice in Japan", OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on October 7, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/886/the-staff-of-life-rice-farming-in-meiji-japan-vintage-photographs

Hans Brinckmann

Geweldig, Kjeld! Je passie voor oude foto’s is nog steeds levend!

Hans

#000721 ·

Kjeld

@Hans Brinckmann: Dank je Hans! Ja, de passie voor geschiedenis, Japan, schrijven en oude foto’s brand heftig door ❤️

#000722 ·