PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5 | PART 6 | APPENDIX

This is Part 6 of an essay about how people stayed warm in old Japan.

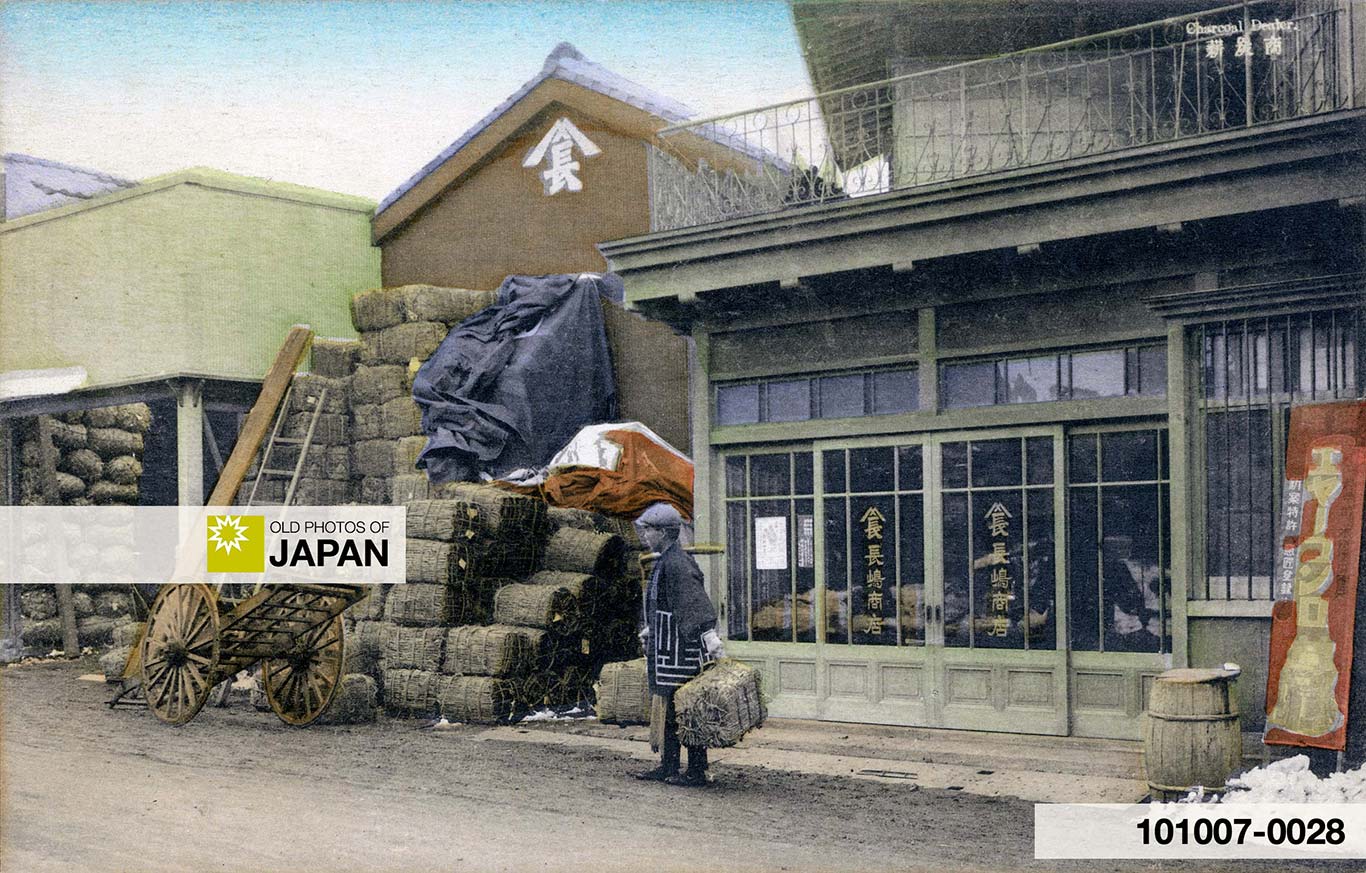

A young employee of a charcoal dealer carries packs of charcoal. An extensive charcoal infrastructure as well as ingenious methods kept the fires in Japan’s millions of hibachi burning.

This site is funded by readers like you

Old Photos of Japan provides thoroughly researched essays and rare images of daily life in old Japan free of charge and advertising. Most images have been acquired, scanned, and conserved to protect them for future generations.

I rely on readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support this work.

Feeding the Fire

From the Edo Period (1603–1868) on, the hibachi charcoal heater played an increasingly important role in daily life. By the late Meiji Period (1868–1912), most homes and shops had several, while restaurants, teahouses, and inns often had one for each and every guest.

Such widespread usage required massive production and distribution networks for both hibachi and charcoal. These were mostly created during the Meiji Period. Especially railways were crucial. As they crept into the farthest corners of the nation, they connected previously isolated areas with the rest of the nation, allowing their inhabitants to produce charcoal as a cash crop.

With charcoal as one of Japan’s chief forest products, charcoal production became an integral part of Japan’s mountain landscape. Charcoal kilns were usually set up on the very mountain slopes where the trees were cut. The view of pale smoke of a kiln softly rising and spreading over a verdant mountain slope was intimately familiar to both locals and visitors.

Charcoal burning was profoundly hard work, done almost entirely by sheer muscle power, as can be seen in this brief film clip from 1930 (Showa 5):

Charcoal’s reign lasted all the way through the 1950s. A University of Michigan field study focusing on the life of common people in two small villages in Western Japan has left us a brief description of charcoal burners during that period:42

Their packed-earth kilns, which are located in the very tracts from which the charcoal wood is cut, are constructed by the operator’s household with occasional assistance of hired labor. A kiln is elliptical, built on a rough log frame and varying in size according to the area of forest to be burned. Most charcoal is made of pine or cork oak, and, as in lumbering, only the wood in the tract to be burned is purchased by the operator, the price being based on the quality of the trees and the probable volume of wood. Rarely do charcoal burners of Matsunagi operate far from home, for during the five days or so that the wood burns, the operator must be able to come and go at any hour.

As in previous centuries, finished charcoal was packed in bundles held together by woven straw and carried down the mountain on the backs of both men and women. Dealers sold it on to the rest of the country.43

Finished charcoal is packed in containers of pampas grass (Miscanthus sinensis) which are made in the household, mostly by old men. There is a cooperative association of charcoal burners in the mura, but it has little function except to inspect the finished charcoal in order to maintain its quality. The charcoal burner, alone or with the help of neighbors or relatives, leases woodland and disposes of his goods to dealers in nearby towns. The market for charcoal is seasonal, but burners in Matsunagi continue to operate their kilns through the summer, storing the product until colder weather. Although charcoal burning does not require high capitalization, it is costly in time and demands considerable experience and skill. It is, however, one trade that a man with no technical training and little property can attempt with the prospect of earning a modest livelihood.

While railways facilitated distribution, Japan’s furious industrialization of the Meiji Period greatly extended the range of hibachi and related products. For example, the Shigaraki district in Shiga Prefecture expanded its production of ceramic hibachi so much that it ended up dominating the market nationally. While Kawaguchi in Saitama Prefecture saw a host of newly built foundries throwing themselves into the production of cast iron hibachi and tools, as illustrated by this brochure for a Kawaguchi foundry:

Keeping the Fire Burning

Massive production and distribution networks led to the hibachi’s enormous success. But it was ingenious yet simple systems that kept the hibachi fire burning.

The most important was leaving space between the charcoal pieces so air could flow through. To further control air flow, a hole was dug into the insulating layer of ash. The charcoal was placed into this hole and the ash heaped up around it to create something like a tiny volcanic crater. This made the charcoal last longer.

Each hibachi came with an array of specialized tools. The ash was arranged with a spatula shaped rake named hai-narashi (灰ならし). Its teeth created beautiful scored lines in the ash.

To arrange the charcoal so that it burned most efficiently, special metal chopsticks known as hibashi (火箸, literally fire chopsticks ) were used.

The fire was kindled with an uchiwa fan or a hifukidake (火吹き竹), a bamboo tube used to gently blow air into the fire. If blown too hard the ash would scatter. Countless kids likely learned this the hard way.

Two of the most ingenious systems to keep the fire burning were the jōtan and the hifuki daruma :

◆ Jōtan

The jōtan (助炭) was a hibachi cover made of washi paper stretched over a wooden frame. By preventing unnecessary burning caused by drafts the charcoal lasted longer.44 The jōtan was especially placed over the hibachi when there were no guests, often with the kettle still on it.

No vintage photos of jōtan were believed to exist — they are even rare in ukiyoe woodblock prints. But I happen to have a photo of a jōtan in my private collection.

Though they are rare in vintage images, jōtan are common in haiku poems as a word to denote winter. Today, Jōtan are still used in the Japanese tea ceremony, although the design is quite different from traditional jōtan. Most modern jōtan look like a pyramid without a top.

◆ Hifuki Daruma

The hifuki daruma (火吹き達磨) was perhaps the most fascinating tool for the hibachi. This small, hollow copper daruma doll measured 5 to 8 centimeters in height and weighed around 9 grams. It featured a tiny, millimeter-wide hole as its mouth.

The hifuki daruma was first placed in burning charcoal, allowing the air inside to heat up and expand, forcing it out. The doll was then quickly submerged in water. This sudden cooling caused the air inside to contract rapidly, creating a strong suction that drew water in through the pinhole.

Next, it was placed near the hibachi fire. When the water inside heated up, steam was blown onto the burning charcoal. This triggered a chemical reaction that increased the fire’s combustion efficiency. In other words, this unassuming tiny doll helped conserve charcoal. It was an extremely convenient and powerful tool.

Unfortunately, the process was risky. Passing steam over burning charcoal creates water gas, which can lead to carbon monoxide poisoning.45

Interestingly, a contemporary advertising flyer and manual for the hifuki daruma suggests it was promoted as a tool to kindle the fire. There is no mention of the charcoal lasting longer. This begs the question if the manufacturer was aware of the chemical reactions and health risks.

◆ Hikeshi Tsubo

Another important yet unassuming tool was the hikeshi tsubo (火消し壺), a pot used for extinguishing burning charcoal. It was also known as sumikeshi tsubo (炭消し壺).

The fireproof pot was generally made from materials like ceramics or metal and designed to be airtight. As soon as charcoal was placed inside, the lid was placed on top. This cut off the oxygen supply and extinguished the fire.

Extinguished charcoal — known as keshitan (消し炭) — was priced for its gentle flame. It was also used as a starter fuel because it ignited more easily. Instead of letting leftover charcoal burn to ashes, it was effectively recycled for future use.

An encyclopedia from 1927 (Showa 2) stresses this function:46

The hikeshi tsubo, though sitting silently in the corner of the kitchen with an unassuming and somewhat grimy appearance, actually plays a crucial role in fire safety and fuel conservation.

Although most systems make sense, some customs were handed down without apparent justification. For example, an old Japanese saying, summer down, winter up (夏下冬上, kakatōjō) advised people to place hot charcoal on the bottom of the pile in summer, and on top in winter. This would make it easier for fresh charcoal to catch fire in the respective season. There is no scientific evidence for this.

More likely, putting burning charcoal on top in winter felt warmer, while putting it at the bottom in summer felt cooler.

Learning Young

Japanese learned to use the hibachi from an early age — mostly by imitation. The University of Michigan study of daily life in two small villages during the early 1950s, has a beautiful description of this process:47

Instruction in adult techniques is carried on through ceaseless, patient demonstration, the child being encouraged to do the thing himself, imitating the movements of the adult as best he can. I noted striking examples of this process on several occasions. A four-year old boy, who because he was the youngest child was constantly with his widowed mother, was present once when his mother was making tea and serving it with cakes to two guests. There was a charcoal brazier in the room, a box of charcoal and iron chopsticks with which to handle it. She had a tea set, a kettle and tea and water. As she talked, she was building a fire over which to heat the water. Her small son watched her lift the charcoal from the box into the brazier a number of times and then wrested the chopsticks from her faintly resisting fingers and continued the process himself. When he dropped a piece she would, without interrupting the flow of conversation, adjust the chopsticks to his fingers and help him pick it up, after which he would continue unaided for a time.

This learning process extended far beyond the charcoal. It included the practical use of the hibachi, such as making tea:48

This same procedure took place with pouring the water, putting the kettle on the fire, cleaning the tea cups, putting tea into the pot, pouring on the boiling water, pouring the tea and serving it. When she got up to get the cakes from the kitchen, he pulled at her, demanding to know where and why she was going, and hung on to a kimono sleeve until she told him. Thereupon he demanded to be told where the cakes were and learning, insisted on getting them himself.

Hibachi Today

As mentioned in Japan’s Mistresses of Fire, old-fashioned charcoal hibachi have made a cautious revival during the past two decades. Lots of people share their experience with this humble heater on social networks and blogs. Specialized businesses have sprung up, and there are countless sites with advice.

Some of the best online advice I have found is on Hibachiya (ヒバチヤ), a site run by a Tokyo based antique shop. It features detailed explanations, a video, photos, illustrations, and safety precautions. Even if you don’t read Japanese, it is worth checking out with an online translation service like Google Translate.

The Hibachiya video below is a brief introduction to using a traditional hibachi in modern Japan. It is in Japanese, but the footage speaks for itself. Both the above link to the Hibachiya site and the video introduce additional hibachi tools not mentioned in this article.

Warning

To prevent carbon monoxide poisoning or fire, a traditional hibachi requires a well-ventilated space, specific types of charcoal, and knowledge of safe handling. Study safety requirements before using one indoors.

Notes

42 Cornell, John Bilheimer (1969). Two Japanese Villages. New York: Greenwood Press, 143.

43 ibid

44 西村俊範 (2024). 江戸・明治時代の庶民風俗(3) ―長火鉢・安売屋・丑の刻参り・照明具― 付論・江戸・明治時代の庶民民族(続)補遺. 京都先端科学大学人間文化学会, 人間文化研究 52号, 216–218.

45 Wikipedia, 火吹きダルマ. Retrieved on 2025-03-09.

46 及川久太郎 (1927).『学習資料百科全書 第9巻』東洋図書, 11.

「火消壺は、きたないかつこうをして臺所の隅にだまつて居るが、これで中々、火の用心だの、燃料の節約だのという重要な任務を帯んで居るのである。」

Also: 『ならしの風土記』習志野市 (1980), 128–129.

47 Cornell, John Bilheimer (1969). Two Japanese Villages. New York: Greenwood Press, 73.

48 ibid

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Outside 1930s: How Japan Kept the Fire Burning, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/957/hibachi-meiji-taisho-showa-how-japan-kept-the-fire-burning

There are currently no comments on this article.