The game that these two young women are playing was once the most popular game in Japan, known by all. Now few people have even heard of its name.

They are playing kitsuneken (狐拳, fox hand game), also known as tōhachiken (東八拳), which is a more organized form of the game. Similar to janken (rock paper scissors), the gestures are village headman, hunter and fox. Kitsuneken was once a commonly played game in Japan.

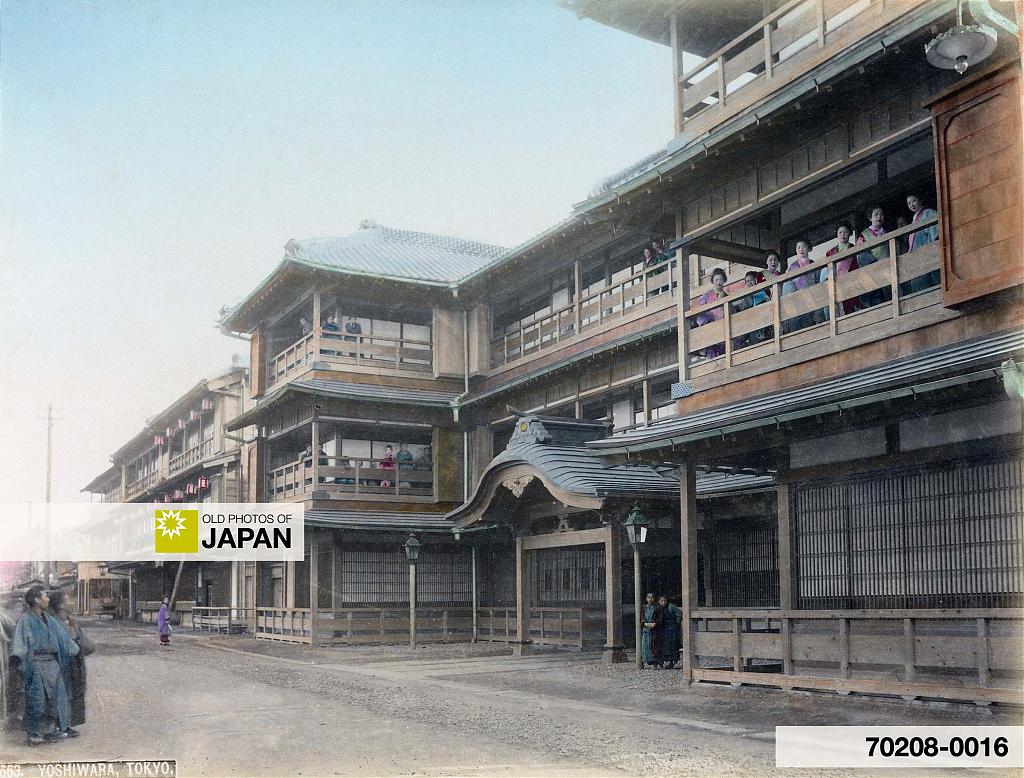

It was especially popular as a drinking game, the loser of a bout had to drink sake. There were also strip versions—popular at brothels—in which the loser had to take off a piece of clothing after each lost bout.

After Yokohama was opened to foreign trade in 1859 (Ansei 6), prostitutes at the town’s large brothel district played this game during dance performances for foreign customers. Every so often the music stopped, and the girls played kitsuneken. The person who lost, took off a piece of clothing. The music, and the games, continued until all of them stood in their full natural glory.1

The 1953 movie Shukuzu (縮図), known in English as Epitome, features a scene in which Japanese actress Nobuko Otawa (乙羽 信子, 1924–1994) plays a geisha in a fiery and intense game of kitsuneken with a customer who hopes to disrobe her. The game actually starts as a strip game, but is turned into a drinking game when it becomes risky for Otawa’s character. Instead, she ends up getting totally plastered.

Kitsuneken was so deeply entrenched in daily life that as tōhachiken it even had an iemoto system (家元, head of a school of traditional Japanese art), rankings, and competitions. Some of these iemoto still exist, and the game is still played today. But mainly as entertainment by geisha, and by the members of a small tōhachiken association in Tokyo.2 Remarkably few Japanese are familiar with kitsuneken. Even fewer have played it. Unsurprisingly, the strip version has completely vanished.

Gestures

Just like with janken, in kitsuneken each gesture beats one, while loosing to another: the village headman controls the hunter, who shoots the fox, who tricks the headman. But while in janken each player uses a single hand, in kitsuneken two hands are used for the gestures, often in an exaggerated manner.

| Role | Japanese | Gesture |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Headman | 庄屋 (shōya) 旦那 (danna) |

Formally seated with hands on legs. |

| 2. Hunter | 猟師 (ryōshi) 鉄砲 (teppō) |

Holding an imaginary rifle. |

| 3. Fox | 狐 (kitsune) | Holding both hands up with palms towards the partner. |

Because these gestures follow each other up quickly, they require a rhythm to ensure that they happen at the exact same time. Often, music was used for that. But it is also possible to provide rhythm orally, as can be seen in the clip below of a 2019 streetside game in Tokyo’s Asakusa entertainment district.

The person on the left is Hananoya Juteru (花廼家 壽輝, tōhachiken name), a seventh generation iemoto. Her family has been involved with tōhachiken since the iemoto was founded in 1869 (Meiji 2).

She is ranked as a yokozuna, a title borrowed from sumo denoting the highest rank. Notice the miniature stage resembling a sumo wrestling ring (土俵, dohyō).

Power of the Fox

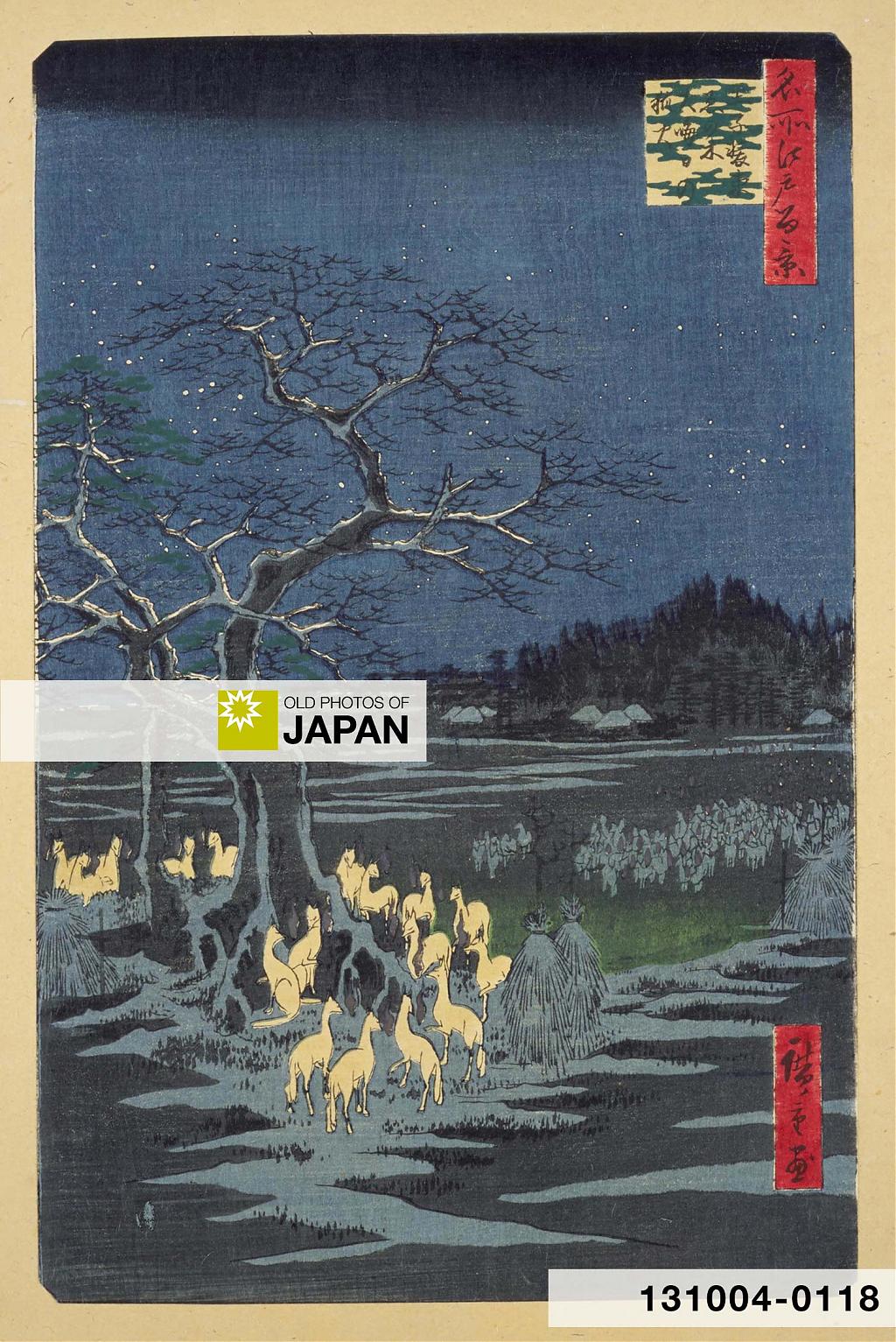

It may at first seem unnatural that the fox defeats the village headman. But in old Japan, people believed that foxes possessed supernatural powers, including the ability to shapeshift into human form. Traditional Japanese folklore features countless stories of foxes tricking or even bewitching humans.

A form of this belief can still be observed today. Foxes are the servants of the Shinto deity Inari, who is the patron of prosperity for farmers and merchants, and protects the rice harvest. Japan counts more than 30,000 Inari shrines. The most important one is Fushimi Inari Taisha in Kyoto, which overflows with fox statues.

There is a fascinating Inari-related story about powerful warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi (豊臣秀吉, 1537–1598), one of the three Great Unifiers of Japan. In 1591, he wrote a letter to the deity when the wife of his retainer Ukita Hideie (宇喜多 秀家, 1573–1655) was believed to be possessed by an old fox.3 In The life of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, British journalist Walter Dening (1846-1913) shared a translation. The original was kept at the Tōdaiji temple in Kyoto, wrote Dening.4

To Inari Daimyojin, My lord, I have the honor to inform you that one of the foxes under your jurisdiction has bewitched one of my servants, causing her and others a great deal of trouble. I have to request that you make minute inquiries into the matter, and endeavor to find out the reason of your subject misbehaving in this way, and let me know the result. If it turns out that the fox has no adequate reason to give for his behavior, you are to arrest and punish him at once. If you hesitate to take action in this matter I shall issue orders for the destruction of every fox in the land. Any other particulars that you may wish to be informed of in reference to what has occurred, you can learn from the High Priest, Yoshida.

Origins of Ken

Ken (拳, literally “fist”) hand games are believed to have existed in Japan as long ago as the Heian Period (794 to 1185). The oldest form appears to be mushiken (虫拳, literally “insect ken”). The game involves a snake (蛇, hebi), frog (蛙, kaeru), and slug (蛞蝓, namekuji).

Like in janken, mushiken is played with the right hand. But only a single finger is used. The snake (index finger) defeats the frog (thumb), which defeats the slug (little finger), which in turn defeats the snake.

Interestingly, in the 1930s and 1940s, children in the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) played a game known as soeten with exactly the same gestures. But they represented an elephant (thumb), a human (index finger), and an ant (little finger). The elephant trampled the human, who trampled the ant, which crawled into the trunk of the powerless elephant.5

Although the gestures are the same, there is one obvious difference. In Japan the index finger beat the thumb. But in the Dutch East Indies, the thumb beat the index finger. So, the two gestures on the right of the above image are reversed.

Edo Ken Boom

Ken games really came into their own from the Edo Period (1603–1868) when ken as a drinking game reached Japan from China. The geisha, musicians, and prostitutes who worked in Japan’s licensed entertainment districts embraced the game and made it a fun social event with drink, music, and dancing. Prostitutes turned ken into a strip game which essentially amounted to foreplay. The creativity of these women resulted in an explosion of variety.

Hironori Takahashi (高橋浩徳), a researcher of the history of games at the Institute of Amusement Industry Studies of the Osaka University of Commerce, has counted more than 200 different ken versions.6 The three figures of the game were continuously replaced with new ones, occasionally inspired by real people.

One occasion when this happened featured the Russian ambassador Nikolai Rezanov (1764–1807). He visited Japan in 1804 (Bunka 1) in an attempt to conclude a commercial treaty. To shorten the time that he had to wait for the Japanese government’s answer to Russia’s request, the Japanese authorities provided him with a prostitute. Reportedly, the ambassador fell in love with her.

The amused inhabitants of Nagasaki quickly created a ken in which the local government representative defeated the prostitute, who defeated Rezanov who defeated the representative. In real life, Rezanov was not that lucky. His diplomatic efforts ended in failure. Rezanov left Japan—and his prostitute—in 1805.7 Sadly, the history books do not tell us if they ever played their own ken game.

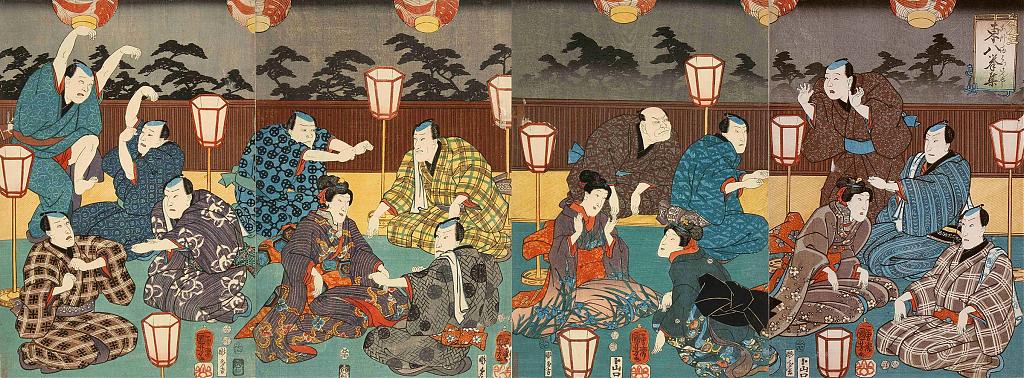

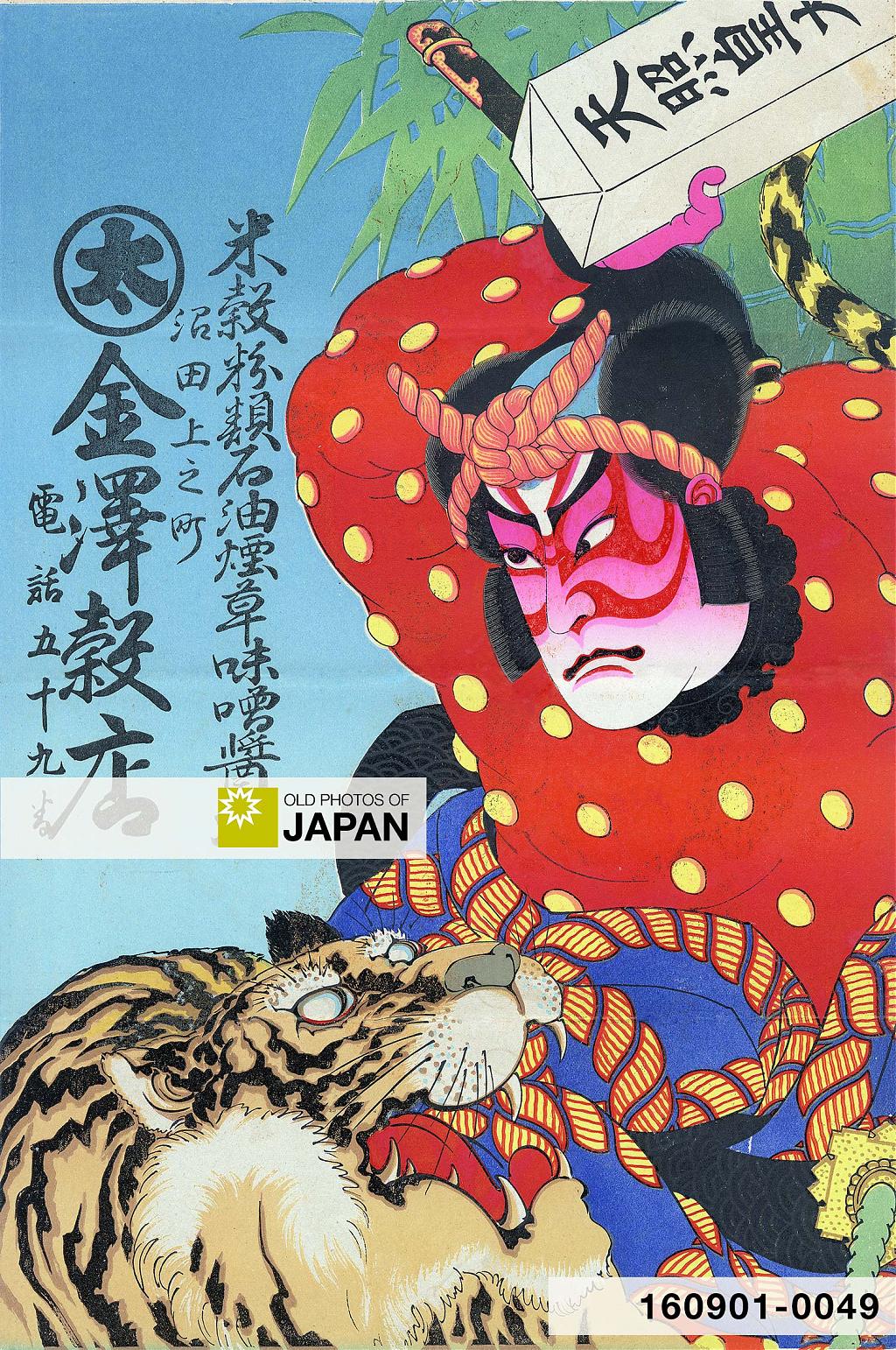

An aspect of Japanese life that especially had a massive influence on ken games was the theater world. There was intense interaction between ken games, and kabuki performances and actors.8 Ken were regularly incorporated in performances, boosting both the popularity of the games and that of the actors.

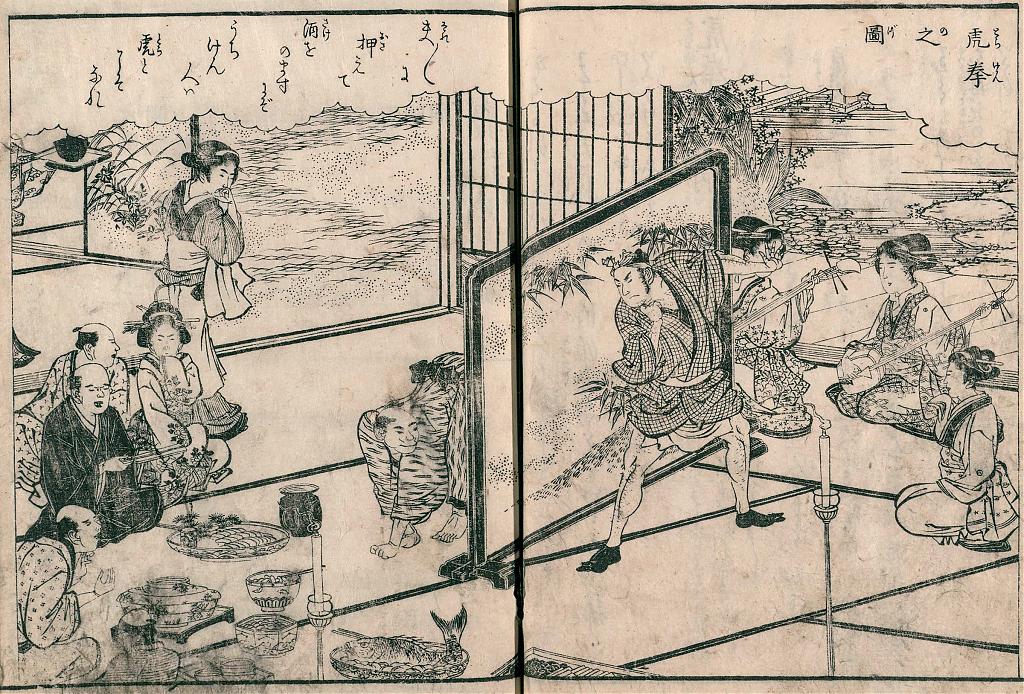

One of the most popular ken games, toraken (虎拳, tiger ken), was even inspired by a play—The Battles of Coxinga (国性爺合戦, Kokusenya Gassen). Originally written as a bunraku puppet play by Japanese dramatist Chikamatsu Monzaemon (近松 門左衛門, 1653–1725) in 1715, this play was loosely based on the life of the Chinese-Japanese warrior Zheng Chenggong (鄭成功, 1624–1662).

Zheng was born in Hirado in what is today Nagasaki Prefecture. He was the son of a Chinese merchant and a Japanese woman, a hāfu as we would say now. Raised with the Japanese name Fukumatsu (福松), he moved to Fujian province of Ming Dynasty China (1368–1644) when he was seven years old.

He fought against the Qing conquest of China, and defeated the Dutch colonists in Dutch Formosa (present-day Taiwan). He is also known as Koxinga (國姓爺) and Watōnai (和藤内), the name that Chikamatsu used in his play. Watōnai is used in toraken as well.

In the game, Watōnai killed the tiger, which killed Watōnai’s mother, who—according to the norms of filial piety—had to be obeyed by Watōnai. What made toraken special and popular was that instead of just the hands, the whole body is used to represent the characters.

This requires that the players have to hide from each other behind a screen. Visible to the audience, they dance on music, then emerge as the song ends to display their posture to each other.

To represent Watōnai, a player imitates a warrior stabbing with a lance; the tiger is represented by crawling on arms and legs, and the mother as an old woman walking with a stick.9 This makes the game quite theatrical, and is probably the reason that it is still played by geisha today as entertainment for customers. It is now generally known as tora tora (とらとら; tiger, tiger).

In the following clip of two geisha playing toraken, the postures are exposed at the end. See if you can quickly figure out who won.

Another ken demonstrating the interaction between the real world and the worlds of entertainment, was sangokuken (三国拳, three countries ken), also known as sanbutsuken (三仏拳, three Buddhas ken). It became popular after it was included as a dance in a kabuki play in 1849 (Kaei 2).10

Sangokuken revolved around three countries represented by spiritual figures: the sun goddess Amaterasu Ōmikami for Japan, Confucius for China, and Gautama Buddha for India. Japan beats China, which beats India, which in turn beats Japan.

Like in kitsuneken, both hands are used. Amaterasu is represented by forming a circle with the thumbs and index fingers as a symbol for the sun, Confucius by gestures imitating the stroking of a long beard, and Buddha by pointing one finger to heaven and the other to the ground.

Tōhachiken

From the 1840s onward, the most popular of all ken games was kitsuneken. In 1876 (Meiji 9), the organized version of the game, tōhachiken, even became one of the four most popular things of the year. The others were billiards, a soft drink, and artificial hot springs in the city.11

Possibly, because kitsuneken represented a world view that was real to the Japanese of the late Edo and early Meiji periods. This was a time of great upheaval and uncertainty. Frequent peasant uprisings pitted villagers against the authorities. At the same time, beliefs in the supernatural were at an all-time high. While people were used to praying at Inari shrines, which were everywhere.

Kitsuneken, in a fun way, represented this struggle between the authorities (headman), the common person (hunter), and the supernatural (fox).12

But an even more important reason for the great popularity was that early on, players tried to make the game more interesting by incorporating elements of sumo wrestling into kitsuneken.

This eventually transformed an uncomplicated drinking game into a rule-bound martial art, which players took increasingly seriously. Kensarae Sumai Zue, a ken instruction book published from 1809 (Bunka 6), even introduced training habits:13

Those who want to become good ken players have to play five hundred to six hundred games a day for a period of sixty days, after which they should take a rest for ten days, before they practice again diligently as before for another sixty days, until they play without thinking about their fingers as if it were quite normal. If one reflects deeply about the pattern of one’s fingers in the games after that one will quite naturally become a skilled player.

There is a tendency in Japan to transform mundane activities into a refined art with a specific practice unified as a school, frequently with spiritual overtones. Even humdrum everyday acts like drinking tea, displaying flowers or writing have been transformed into zen-like exercises requiring great amounts of study and practice.

They are essentially deeply codified ceremonies to express—and demand—respect. Respect for the art itself, for the tools, furnishings and materials, but perhaps most importantly for the teachers and practitioners.

Often, the character 道 (dō, tō, michi; way, road, path)—representing the religious tradition of Taoism—has been used in the names of such disciplines. Many martial arts quickly come to mind, but cultural arts have incorporated dō in their name as well. Here are a few of the best known examples:

| Discipline | Japanese | Meaning | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aikidō | 合気道 | Way of harmonious spirit | Martial art |

| Jūdō | 柔道 | Gentle way | Martial art |

| Jūkendō | 銃剣 | Way of the bayonet | Bayonet fighting |

| Karatedō | 空手道 | Way of the empty hand | Okinawan martial art |

| Kendō | 剣道 | Way of the sword | Fencing with bamboo swords |

| Kyūdō | 弓道 | Way of the bow | Archery |

| Chadō or Sadō | 茶道 | Way of tea | Japanese tea ceremony |

| Kadō | 華道 | Way of flowers | Flower arrangement (ikebana) |

| Kōdō | 香道 | Way of Fragrance | Appreciating Japanese incense |

| Shodō | 書道 | Way of writing | Japanese calligraphy |

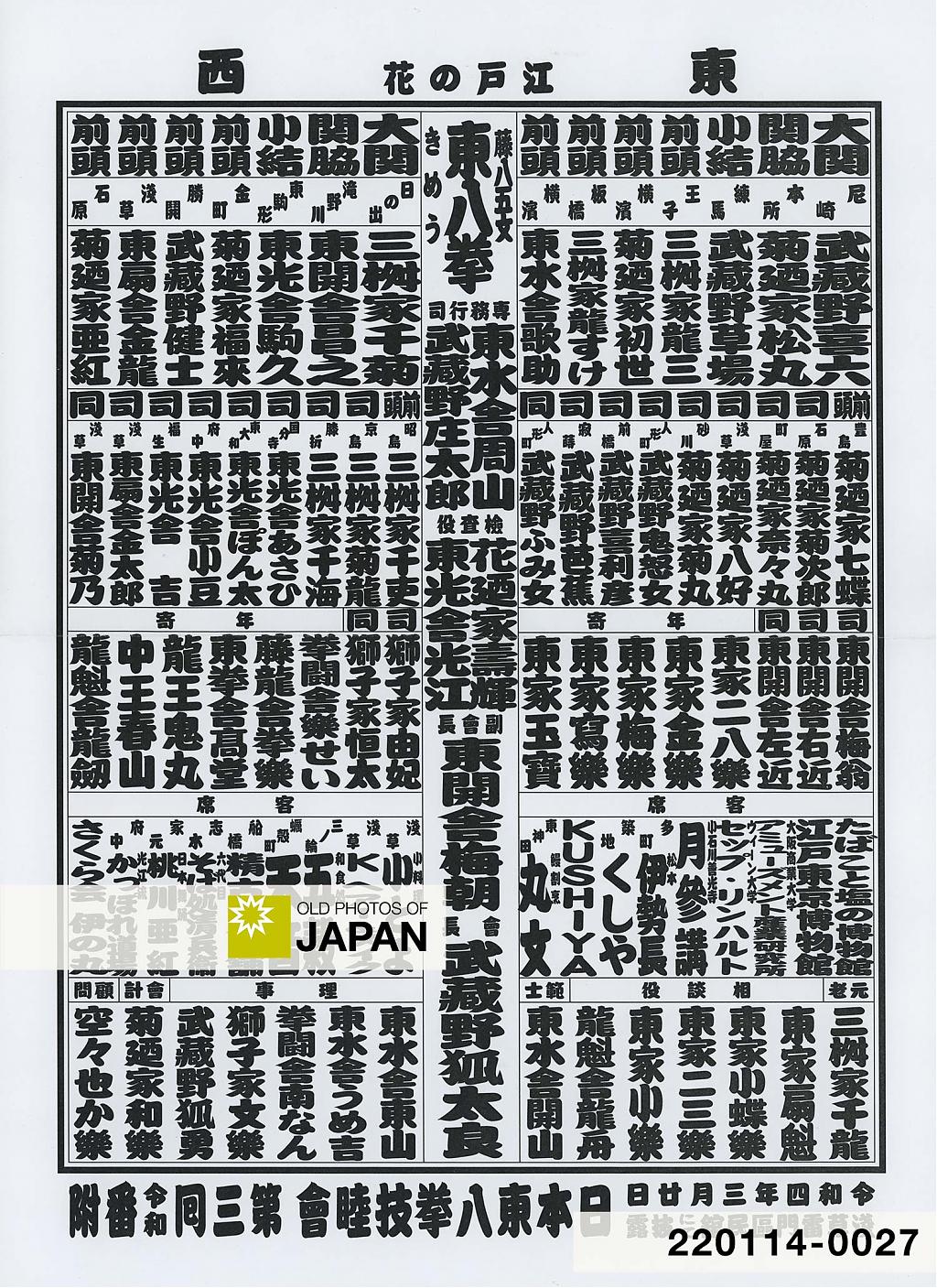

By 1850 (Kaei 3), playing kitsuneken had been transformed into a school in the same vein, with structure, rules, competitions, player rankings, “belts”, and iemoto organizations.14 A new name was created for this more complicated kitsuneken—tōhachiken—to differentiate it from the drinking game with song and dance. It was eventually called tōhachikendō, to make it very clear that it was a serious art.

It is a bit unclear how active the iemoto were after the early Meiji Period. It appears that no banzuke-hyō (番付表, ranking lists) were printed between the late 1880s and early 1900s (Meiji 20s–30s), suggesting there were no competitions. A 1906 (Meiji 39) article about tōhachiken in the Tokyo Asahi Shimbun states that “ken battles almost disappeared for a time, until recently when there were attempts at a revival of the old style.”15

In Home Life in Tokyo, published in 1910 (Meiji 43), Japanese author Jukichi Inouye briefly describes the game, but only references the drinking game, not the competitive version. He notes that by then the game’s popularity was less than in the past: “It is a favourite game at convivial parties, especially if one of the parties is a geisha, though it is not so popular now as it used to be.”16

Somehow, Tōhachikendō managed to survive beyond the Meiji Period. In 1917 (Taisho 6), the various iemoto founded an umbrella organization, Nihon Tōhachiken Mutsumi Kai (日本東八拳技睦會), amidst a new boom.

In 1941 (Showa 16), in the middle of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), and on the eve of the Pacific War (1941–1945), this organization was temporarily renamed Great Japan Tōhachikendō Association (大日本東八拳道会, Dainippon Tōhachikendō Kai).

However, it appears that by this time tōhachikendō was not very well-known anymore. In the book Kenzen Goraku Tōhachikendō (健全娯楽 東八拳道, Wholesome Entertainment: Tōhachikendō), published in 1941, author Magoichi Kubota (久保田孫一) deplores the general ignorance of tōhachiken, while reaffirming its status as a serious art with complicated rules:17

Tōhachiken is played among the ken players according to very strict rules, but this is generally not widely known. Every iemoto had a great amount of authority, and since it was forbidden to let others know one’s ken name at sake-parties and since the better one played the more one had to restrain oneself, the general people knew it only from hearsay and imitated it out of their imagination. Therefore the ken which is performed by geisha at drinking parties is not the real ken; it is not more than an imitation with the hands. They have taken over also several conventions and ceremonies of which they have heard, but seen from the viewpoint of a ken player they are really amusing. A real ken game is not something which is done accompanied by shamisen and the like.

A few years after the end of the war, the association reclaimed its old name, but the popularity of the game steadily declined. An NHK report from 1951 (Showa 26) still assumes knowledge from viewers. But the report below from 1966 (Showa 41), only fifteen years later, already introduces tōhachiken as a rarity. The narrator even questions the game’s appeal to “modern people chasing speed and thrills.”

Today, very few people know either kitsuneken, or its more pretentious offspring, tōhachiken. Some geisha still play kitsuneken, but there are just seven tōhachiken iemoto, and the Nihon Tōhachiken Mutsumi Kai only has about 50 members.

It nonetheless aims to keep tōhachiken alive and educate people about the game, generally in a fun and informal way. Every Sunday, the association organizes tōhachiken meetings at the Asakusa Community Center in Tokyo. Visitors can observe for free.

Concepts

Ken games are zero-sum games with three possible outcomes: a draw, a win or a loss. They are based on the concept of sansukumi (三竦み). San (三) means three, sukumi (竦み) means to be unable to move because of surprise, fear, horror, etc.

Sansukumi describes a situation in which three things have one opponent who is stronger than them and one opponent who is weaker. A wins over B, B wins over C, and C wins over A.

They are strong and weak in different realms. As a consequence, all three are in the exact same situation. In a real-life situation when A has beaten B, A is stuck because it will be defeated by C. It is a three-way deadlock.

Sansukumi is related to mitsudomoe (三つ巴), the design of three comma shapes inside a circle. This universal symbol of East Asian cultures expresses dynamism and a state of equilibrium.18

A dynamic system of items that have comparable superiority in one realm and inferiority in another, results in an equilibrium of equality and retributive justice. In our harsh, unequal and unfair world, this offers infinite solace and hope.

Science

Scholars have studied rock paper scissors for its applications to business strategy, conflict management, biology and other sciences. It is especially a favorite of scholars of game theory, computer programmers, and game developers.

Particularly fascinating is that scientific studies suggest that the structure of ken games is applicable to evolution. Biologists have discovered that it “may enable many species to coexist in the same area by cycling in and out of dominance.”

The bacterium E. coli for example has evolved strains that apply a perfect rock paper scissors setup. “Rock-paper-scissors covers the entire biological universe,” said mathematical biologist Barry Sinervo of the University of California, Santa Cruz in a 2020 interview with online science publication Quanta Magazine.19

It is still early days, but this research could potentially have significant implications for medical research, ecology, environmentalism, and other scientific fields.

Those 18th and 19th century Japanese prostitutes who adapted ken games to their professional needs were onto something larger than they could have imagined.

Do It Yourself

If you now feel eager to try a game of tōhachiken yourself, the following clip has detailed (Japanese) explanations on how to play it.

My hope is that this article will encourage you and your friends to create a ken game for our world. The fact that over 200 ken games were created, suggests that the game can be easily updated to contemporary culture. To bring back its popularity, characters from movies like Star Wars and Star Trek, popular anime, digital games, or even modern politics could be used. It will be fun to select the characters and think up their gestures.

Postscript

When I purchased the postcard at the top of this article way back in 2007, I had no idea of the enormous cultural weight that was hidden behind the simple gestures of the two women.

A few weeks ago, I purchased the photo from the 1920s. It featured a handwritten caption referring to “tokachi kin” (sic), a “game of man, fox and gun.” Searching for tokachi kin, and showing the photo to elderly Japanese while translating the caption, gave no clues.

But a search for “game”, “fox”, and “gun” did. I quickly searched for other images in my collection showing tōhachiken. The postcard was the first one that I found.

Researching this story has been an enjoyable and enlightening journey. Albeit a long one, it took me several weeks to put this article together.

If you enjoy articles like this, please consider supporting my work if you haven’t done so already. Your support allows me to continue to bring this to you.

Notes

1 Linhart, Sepp (1995). Some Thoughts on the Ken Game in Japan: From the Viewpoint of Comparative Civilization Studies. Osaka: Senri Ethnological Studies, 114.

2 The Nihon Tōhachiken Mutsumi Kai (日本東八拳技睦會) is a national organization that aims to keep the game alive. Every Sunday, the association organizes tōhachiken meetings at the Asakusa Community Center in Tokyo.

3 Okanoya, Shigezane, trans. Dykstra, Andrew and Yoshiko (2007). Shogun and Samurai: Tales of Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, and Ieyasu. 109.

4 Dening, Walter (1888). The life of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Tokyo: Hakubunsha, 406.

5 Wikipedia. Steen, papier, schaar. Retrieved on 2022-05-25.

6 東大阪経済新聞 大阪商業大学で「拳遊戯の世界」展 「じゃんけんだけじゃない」、資料250点で紹介 Retrieved on 2022-05-25.

7 Frühstück, Sabine, Linhart, Sepp (1998). The Culture of Japan as Seen Through its Leisure. New York: State University of New York Press, 327.

8 See the research by Austrian Japanologist Sepp Linhart.

9 Linhart, Sepp (2005). Japan at Play: The ludic and the logic of power. Interpreting the world as a ken game. London, New York: Routledge, 37.

Instead of Watōnai and his mother, General Katō Kiyomasa (加藤 清正, 1562-1611) and his mother Ito (伊都) are also used. This version is more common at Kyoto’s Gion district. Japanese Folklore Research Center. Jiraiya & Sansukumi (Pt. 2). Retrieved on 2022-05-27.

10 Linhart, Sepp (2005). Japan at Play: The ludic and the logic of power. Interpreting the world as a ken game. London, New York: Routledge, 41–42.

11 朝倉治彦, 稲村徹元 編(1965)明治世相編年辞典 東京堂, 140.

12 Linhart, Sepp (2005). Japan at Play: The ludic and the logic of power. Interpreting the world as a ken game. London, New York: Routledge, 54.

13 Frühstück, Sabine, Linhart, Sepp (1998). The Culture of Japan as Seen Through its Leisure. New York: State University of New York Press, 331–332.

14 ibid, 332.

15 ibid, 332–333.

16 Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 314–315.

17 Frühstück, Sabine, Linhart, Sepp (1998). The Culture of Japan as Seen Through its Leisure. New York: State University of New York Press, 333–334.

18 Linhart, Sepp (2005). Japan at Play: The ludic and the logic of power. Interpreting the world as a ken game. London, New York: Routledge, 51–52.

19 Arnold, Carrie (2020). Biodiversity May Thrive Through Games of Rock-Paper-Scissors. Retrieved on 2022-05-30.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 1910s: Headman, Hunter, Fox, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/898/tohachiken-kitsuneken-headman-hunter-fox-traditional-japanese-game

Leyla Ummels Çavuşoğlu

Very interesting! This inspired me to play paper rock scissors with the school children from work! I think it will be fun to teach them.

#000730 ·

Kjeld (Author)

@Leyla: Oh, nice! Maybe you can eventually create your own version with new figures and gestures to make the game more applicable to their lives?

#000731 ·

Noel

As always I’m in awe with the amount of research put in every article.

#000732 ·

Kjeld (Author)

@Noel: That is so kind of you to say. Thank you very much. I really enjoy delving deep into the histories of the customs and traditions shown in these images.

#000733 ·

Noel

There is also a short description of the game in the book “We Japanese” by Frederic de Garis: Google Books

#000734 ·

Kjeld (Author)

@Noel: Thank you. That is a great book. Will try to find an original copy. The salesperson mentioned in this explanation often comes up. He apparently shouted three words in a row very similar to the three characters in the game. But historians now say it is not clear if Tohachi really came from a person by that name, or whether such a person even existed.

#000735 ·