A small boy looking straight into the photographer’s lens, a man pulling a cart, a shopkeeper sticking his head out of his shop to look down a street full of shops. This simple scene, immortalized by an anonymous photographer on a day in the early 1900s, shows a street that once was Yokohama’s main route of entry, Nogemachi-dori.

Noge is Yokohama‘s soul wrote Burritt Sabin, author of a wonderful book about the city. It is so for a vast number of reasons.

Noge was a tiny fishing village along the bay when it witnessed Commodore Perry meeting representatives of the Tokugawa shogunate in the shadow of a large camphor tree at nearby Yokohama in 1853. It was present when that neighboring fishing village was opened to foreign trade on June 2, 1859. It not only saw that fishing village grow into one of the largest ports of the world, but often played a key role in making it the city that it is today.

Yet “for most people,” Sabin wrote in a Japan Times Article in 2004, “Noge is out of sight, out of mind.”1

It may be out of sight now, but this was not always the case. Originally known as Kurakigun Tobemura Nogeura (久良岐郡戸部村野毛浦), the little village started its new role during the final years of the Tokugawa shogunate. At this time a new road was made to connect Yokohama to the Tokaido, Japan’s most important and busiest roadway.

Starting near the Tokaido way-station of Hodogaya, this road literally cut through nearby Mt. Nogeyama, passed by the village and then crossed over two bridges before entering Kannai, the area set aside for the foreign traders and diplomats.

As the Kanagawa Magistrate’s Office and a Japanese garrison were established nearby, the fishermen learned to trade and offer services. When traffic increased on the road, the village prospered more and more.

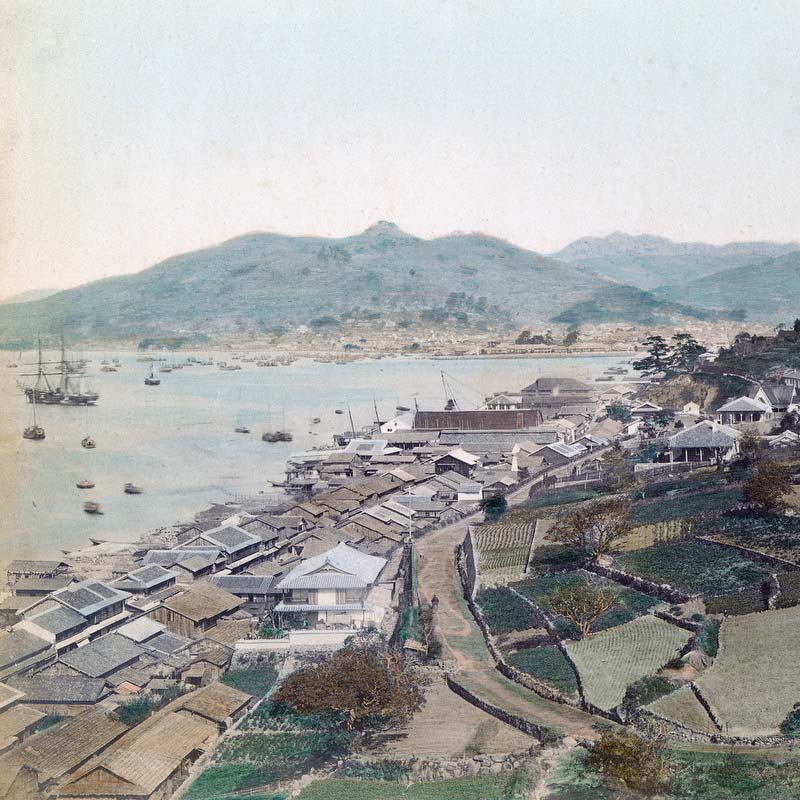

Soon Noge was known among people even outside Yokohama. Nearby Nogeyama with its dramatic view of an exotic Yokohama port full of foreign ships became so popular that during the early 1860s it inspired a song, Nogebushi (野毛節).

But Noge had seen nothing yet. In 1870 (Meiji 3), Iseyama Kotaijingu (伊勢山皇大神宮), a shinto shrine, and Noge Fudo (野毛不動), a buddhist temple, were built nearby and began attracting pilgrims who joined tradesmen on the increasingly busy road.

Only two years later, Japan’s very first rail-connection was opened between Yokohama and Tokyo. Yokohama Station was conveniently close in nearby Sakuragicho, adding to Noge’s bustle.

Not a tiny village anymore, the prosperous business district now known as Nogemachi, became officially part of Yokohama City on April 1, 1889 (Meiji 22).2

At the time of this photo, Nogemachi-dori had grown into a thriving shopping street. It lead from Nogezaka to Miyakobashi (Miyako bridge). After crossing the bridge, the road’s name changed to Yoshidamachi-dori. The road then crossed Yoshidabashi and entered Kannai.

Nearby Nogeyama, with its magnificent cherry blossom, was now a residential area for wealthy merchants. Among the first to have settled there were the rich silk traders Zenzaburo Hara (原善三郎, 1827-1899) and Sobe Mogi (茂木惣兵衛, 1827-1894).3

Unfortunately, Nogeyama’s beautiful estates didn’t survive the Great Kanto Earthquake. They were never rebuilt. Instead, the area was turned into Nogeyama Park.

When fire rained on Yokohama during WWII, Noge was turned into a sad wasteland. But when the US occupation forces confiscated nearby Isezaki-cho and much else of Yokohama after the end of WWII, Noge-machi became a refuge and came to prosper once again. A thriving black market (ヤミ市) grew up. To entertain the people it attracted, theaters mushroomed around it.

At one of these theaters, the Kokusai Gekijo (国際劇場), a street-smart 10-year old daughter of a Yokohama fishmonger mesmerized audiences with a phenomenal singing voice and a personality to match. Her name was Kazue Kato (加藤 和枝), but the world would come to know her as Hibari Misora (1937-1989), without doubt Japan’s most famous post-war entertainer.4

Good times didn’t last. Yokohama evolved. Traffic patterns changed. Other stations took over Sakuragicho station’s traffic. The nearby shipyard closed. By the 1980s, the area was in steep economic decline.

Yokohama City came up with plans to revive it. It built Minato Mirai 21, featuring Japan’s tallest skyscraper, a huge shopping mall, a convention center and much more.

In Nogemachi itself, the Noge Street Performance Festival (大道芸まつり) was started in 1986 (Showa 61). It became extremely popular and soon attracted over 200,000 people.

Somehow, Noge lives on forever.

Notes

1 Sabin Burritt (2004-04-09), Noge, Yokohama: Savor a city’s soul, The Japan Times.

2 中区の町名とその歩み(な行の町名)。野毛町(のげちょう)。横浜市中区役所。

3 Japanese old photographs in Bakumatsu-Meiji Period. Cherry trees at Nogeyama Park (3). Retrieved on 2008-04-12.

4 横浜線沿線街角散歩。野毛町。Retrieved on 2008-04-12.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Yokohama 1900s: Nogemachi-dori, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on February 22, 2026 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/155/nogemachi-dori

There are currently no comments on this article.