Boats are docked in front of a long row of warehouses in Koamicho (小網町) in Tokyo’s mercantile quarter of Nihonbashi. Photographer Kazumasa Ogawa was looking towards Yoroibashi, a steel bridge built in 1873 (Meiji 6), which can be seen in the far right of the image.

Before the city of Edo was built, this area used to be coastline. But by the time this photo was taken, the sea had already been pushed far away and Nihonbashi had transformed into a busy center of commerce.

Nihonbashi was the most densely populated area of Tokyo. It was also the heart of Tokyo’s shitamachi, the low city, where merchants and artisans lived and worked. It was a down to earth and conservative place where Meiji modernization took longer to take root than in nearby Ginza.

Nihonbashi was a place where people worked hard and merchants became rich. During the Edo Period, strict social constraints had kept the rich merchants here, living close to Tokyo’s many poor, who were stowed away in the area’s dark and dreary back-streets. But as soon as the Meiji reformation lifted these constraints, the rich moved their homes to more agreeable sections of Tokyo.

Eventually, business would prefer greener pastures, too. By the end of the Meiji Period, Nihonbashi was slowly loosing its position as commercial center of Tokyo to the newly built Marunouchi district in front of Tokyo Station.

But at the time of this photo, things had not gotten that far, yet. Nihonbashi’s waterways were crowded with boats full of heavy loads ferried in from all over Japan. Nihonbashi river, its banks jammed with white-walled warehouses, was still the busiest waterway in the city.

Japan did not use horse-drawn carriages during the Edo Period and did not really take to them during the Meiji Period either. Cargo was transported on large carts pulled by people or oxen; on the backs of people, horses and oxen; but especially by all kinds of boats, each made for a specific purpose. Tokyo’s waterways had chokibune (猪牙船, long flat bottom boat), takasebune (高瀬舟, shallow-draft boat), tenmasen (伝馬船, large sculling boat) and many others.1

To spoil enemy attacks, the old city of Edo had been deliberately built within a spiral network of moats, rivers, and canals. This made transport by water especially attractive. Early in the city’s development, unloading points called kashi had been created. Warehouses and markets grew up around them. Nihonbashi was the most important one. From here, goods were distributed all over the city.

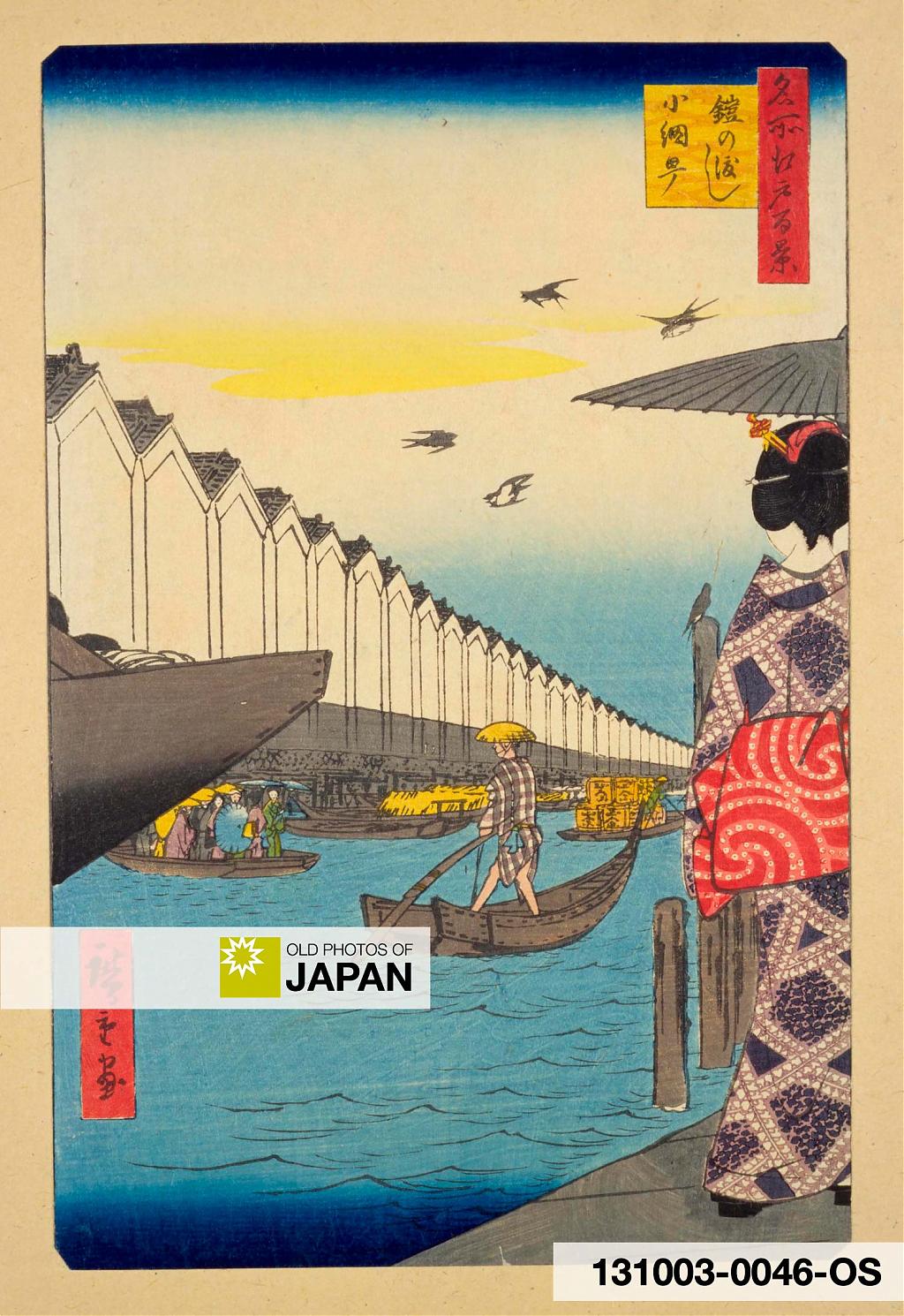

The area’s warehouses gave Nihonbashi a unique look that didn’t only attract the photographer who shot this photo, but also several famous ukiyo-e artists. Utagawa Hiroshige marvelously captured the essence of Koamicho in 1857 in his print “Yoroi no Watashi” (the ferry at Yoroi) included in his series of 100 famous views of Edo.

Unfortunately, most of Nihonbashi, including the warehouses on this photo, was destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 (Taisho 12).

Notes

1. For those interested in Japan’s wooden boat culture, the Aomori Museum of History (formerly the Michinoku Traditional Wooden Boat Museum) in Aomori and Douglas Brook’s site are highly recommended.

2. This image is taken from exactly the same location as Tokyo 1890s • Koamicho, Nihonbashi, so I decided to use the same text for this photograph. Interestingly, in the other image, the Yoroibashi Bridge is deliberately kept outside the photographer’s frame.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Tokyo 1890s: Koamicho, Nihonbashi, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/763/koamicho-nihonbashi

There are currently no comments on this article.