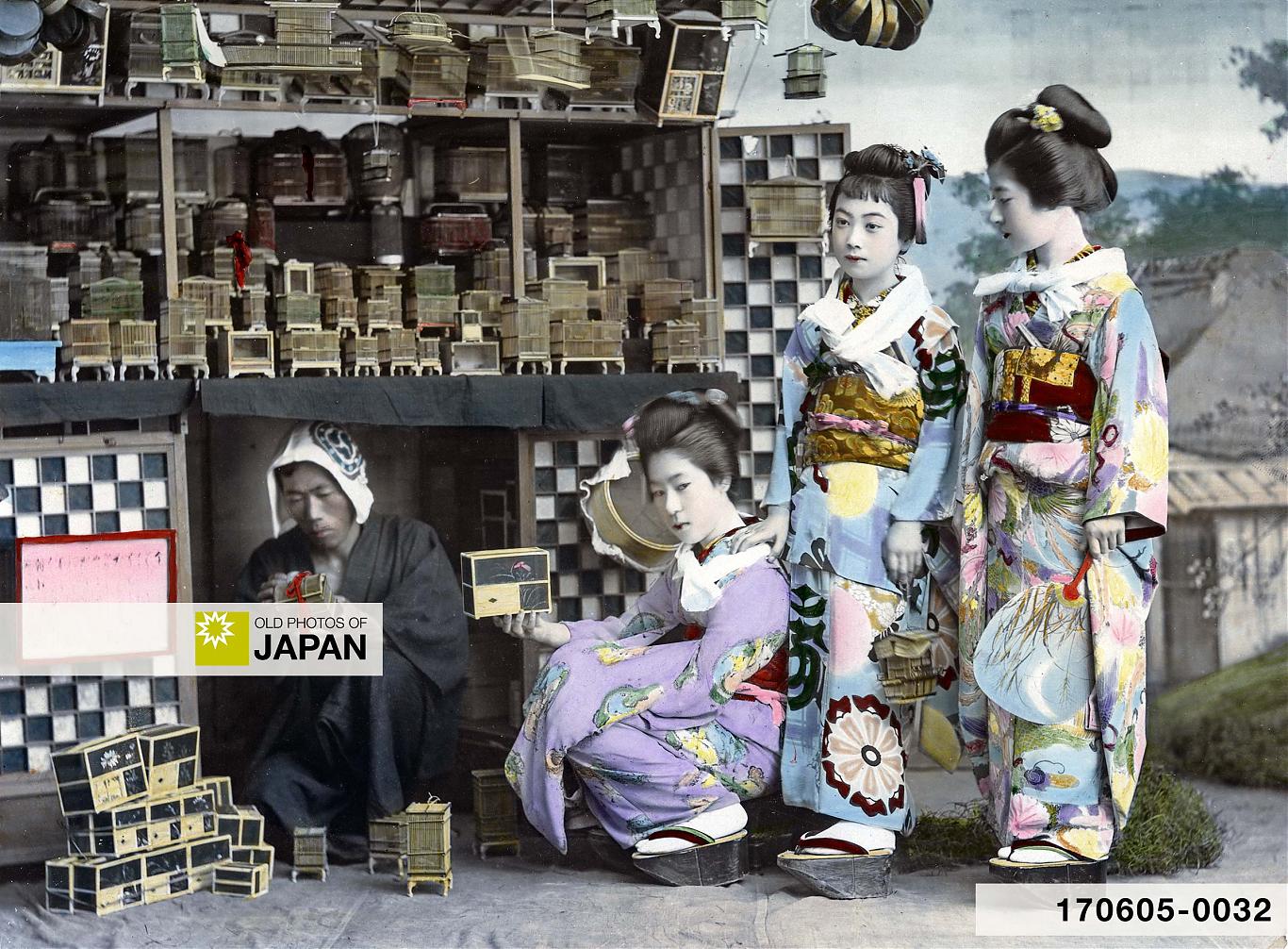

A studio photo of maiko posing in front of the portable street stand of a singing insect vendor. Vendors sold a variety of insects changing with each season.

Japanese summers and autumns have a unique soundtrack, the songs of cicadas, or semi (蝉). Nothing symbolizes these seasons like the sounds of Japan’s 34 species of semi. Different species—each with their own unique song—appear in different months. Different species even sing at different times of the day. Because they are truly everywhere, many Japanese can identify the month, and even the time of day, from a semi’s song.

Japanese filmmakers often take advantage of this. To indicate that a scene takes place in late summer, they will add the sound from a species that only appears then. Or they use the sound of a particular species to evoke a specific emotion. Contemporary Japanese artist Makoto Aida (会田 誠, 1965) explained this in a 2019 interview with the Japan Times :1

The species that people like best is the one that calls when the sun is going down and the day has cooled off. They’re called higurashi. People feel relieved that the heat has gone down slightly and it’s a little more comfortable. It’s a nice feeling. That sound appears in films a lot.

The semi is just one of countless insect species that have embedded themselves deeply into Japanese culture. Japan has a fascination with insects that reaches back many centuries.

Cultural references to insects can already be found in the Tale of Genji, the world’s first novel, written in the early eleventh century by the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu. In one scene, girls are placing insect cages in the garden—presumably to catch insects—for the high-ranking court lady Akikonomu:2

Akikonomu had sent some little girls to lay out insect cages in the damp garden. They had on robes of lavender and pink and various deeper shades of purple, and yellow-green jackets lined with green, all appropriately autumnal hues. Disappearing and reappearing among the mists, they made a charming picture. Four and five of them with cages of several colors were walking among the wasted flowers, picking a wild carnation here and another flower there for their royal lady.

Another source from the eleventh century recounts an emperor ordering his pages and chamberlains to go to Kyoto’s Sagano district to hunt for insects. They are put into a cage that is respectfully presented to the empress. The evening is spent drinking sake and composing poetry, with the insects providing the background music.3

Insects are mentioned in many thousands of haiku poems. They also appear in an endless variety of paintings, drawings and screens, as designs on everyday household items, and even as decorations on samurai sword fittings.

Insects were not only decorations on the warriors’ sword fittings. During the late sixteenth century—a period of constant civil war—military commanders even kept insects to comfort themselves.

Over the centuries, Japan’s city-dwellers developed the custom of visiting the countryside during autumn to enjoy the sounds of insects. Just like people nowadays go cherry blossom-viewing.

Certain spots were famous for specific insects. Eleven places became especially famous all over Japan for their insect music. The best places to hear the matsumushi (松虫, pine cricket) for example, were Arashiyama in Kyoto, Sumiyoshi in Settsu (Osaka), and Miyagino in Mutsu (northeastern Japan).4

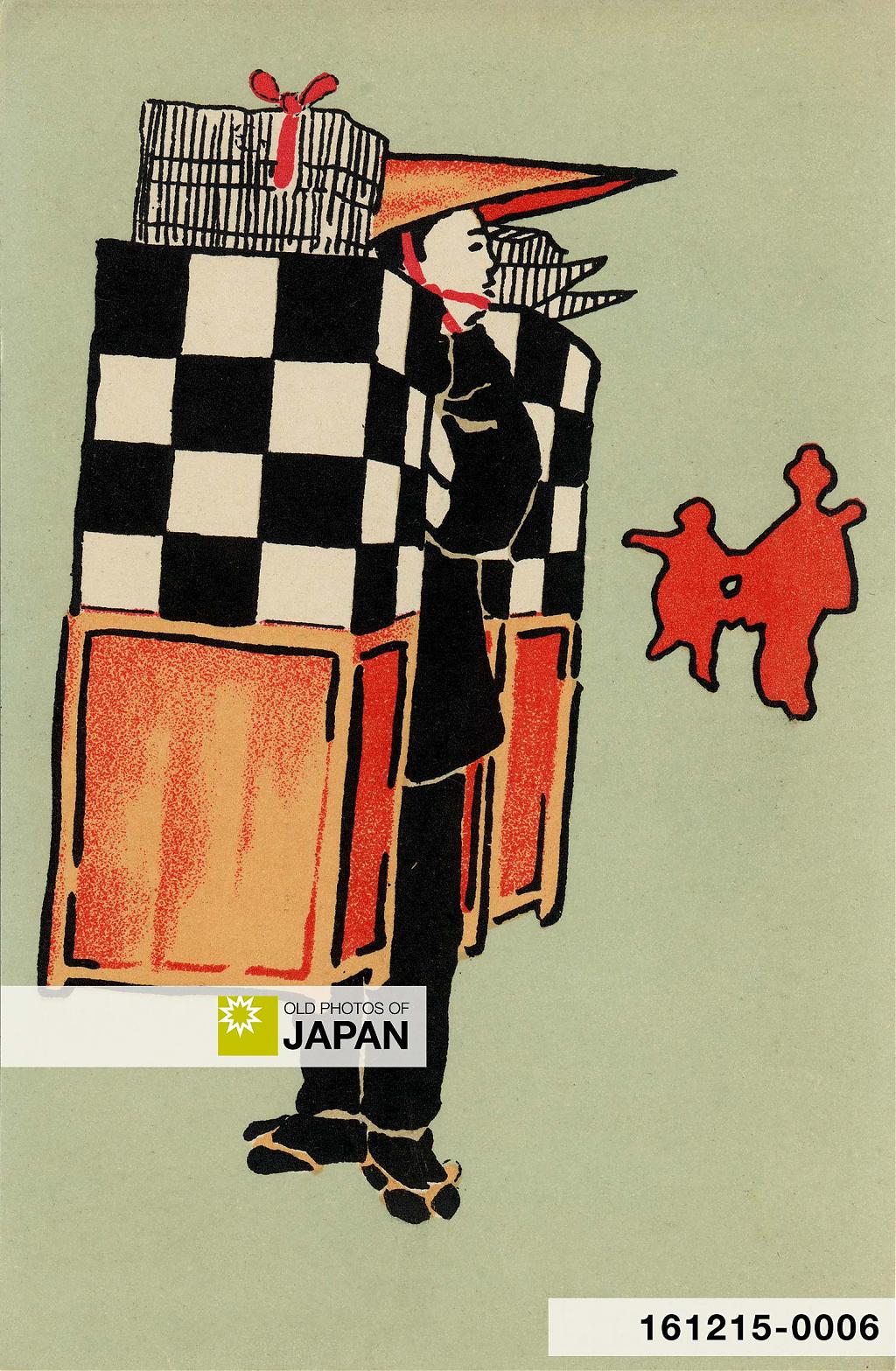

This custom faded away when insect vendors became common. By the seventeenth century, they seemed to have already been common enough for customers to go search for a specific insect vendor. In his dairy, the Japanese poet Takarai Kikaku (宝井其角, 1661–1707) expresses his disappointment about a failed search in Edo (present-day Tokyo) for dealers of the Kirigirisu cricket (キリギリス). The episode suggests that he could easily find vendors selling this cricket elsewhere.5

It is unclear how large the business was at this time. But it all came to a sudden halt in 1687 (Jōkyō 4). The fifth shogun, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi (徳川 綱吉, 1646–1709), issued an edict prohibiting the buying, selling, and keeping of insects. The measure was part of a series of edicts forbidding cruelties to living things (生類憐れみの令) issued during the 1680s and 1690s. As a result, the profession completely vanished from Japan’s streets.

It took a century before insect vendors finally made a comeback. It started with a vendor of oden, the Japanese one-pot dish. His name was Chūzō (忠蔵). Born in Echigo (current-day Niigata Prefecture), Chūzō had settled in Edo’s Kanda district. During one of his sales rounds he decided to catch some suzumushi (鈴虫, bell crickets) and to feed them at home.

Their fragile bell-like sounds charmed the neighbors. They paid Chūzō for a few crickets for themselves. Other people followed. Soon, so many people wanted his insects that he gave up the oden business. He became an insect vendor instead.

Chūzō just caught and sold insects. But a customer called Kiriyama (桐山) came up with the idea to breed them. Chūzō provided him with different varieties of males and females and Kiriyama eventually succeeded in breeding not only suzumushi, but also kantan (邯鄲, tree cricket), matsumushi, kutsuwamushi (クツワムシ, another type of cricket), and other popular singing insects.

He discovered that if he kept the insect jars in a warm room, the insects would hatch much faster. The large supply that Kiriyama was now able to provide was sold by Chūzō. The two men unwittingly developed an extremely profitable business.

Their success inspired other businessmen to follow their example and to improve on their methods. This in turn gave other people the incentive to build insect cages. Chūzō had accidentally created a whole new industry, encompassing breeding, manufacturing, and sales.

Due to the great popularity of the new business, Edo insect vendors were organized into an association known as the Edo Mushi Ko (江戸虫講, Edo Insect Association). A law was issued to limit their number to 36, effectively monopolizing the trade in Edo.6

When Greek-Japanese author Lafcadio Hearn (1850–1904) made Japan his home in 1890 (Meiji 23) and began introducing the yet unknown culture of Japan to the West, the insect selling business had been around for almost exactly a century. It was now deeply integrated into Japanese society and Hearn was fascinated.

In 1898 (Meiji 31) he published a detailed essay about Japanese singing insects and the insect selling business. This is possibly now one of the best contemporary sources for this custom. Hearn starts his essay off by describing how the vendors’ noisy stands could be found at colorful temple festivals:7

If you ever visit Japan, be sure to go to at least one temple-festival—en-nichi. The festival ought to be seen at night, when everything shows to the best advantage in the glow of countless lamps and lanterns. Until you have had this experience, you cannot know what Japan is—you cannot imagine the real charm of queer-ness and prettiness, the wonderful blending of grotesquery and beauty, to be found in the life of the common people. In such a night you will probably let yourself drift awhile with the stream of sight-seers through dazzling lanes of booths full of toys indescribable—dainty puerilities, fragile astonishments, laughter-making oddities; you will observe representations of demons, gods, and goblins; you will be startled by All this may not be worth stopping for. But presently, I am almost sure, you will pause in your promenade to look at a booth illuminated like a magic-lantern, and stocked with tiny wooden cages out of which an incomparable shrilling proceeds. The booth is the booth of a vendor of singing-insects; and the storm of noise is made by the insects. The sight is curious; and a foreigner is nearly always attracted by it.

Hearn explains that “in the aesthetic life of a most refined and artistic people, these insects hold a place not less important or well-deserved than that occupied in Western civilization by our thrushes, linnets, nightingales and canaries.”

He then implores to distinguish the “insect-musicians” he introduces from semi :8

I think that the cicadæ—even in a country so exceptionally rich as is Japan in musical insects—are wonderful melodists in their own way. But the Japanese find as much difference between the notes of night-insects and of cicadæ as we find between those of larks and sparrows; and they relegate their cicadæ to the vulgar place of chatterers. Semi are therefore never caged. The national liking for caged insects does not mean a liking for mere noise; and the note of every insect in public favor must possess either some rhythmic charm, or some mimetic quality celebrated in poetry or legend.

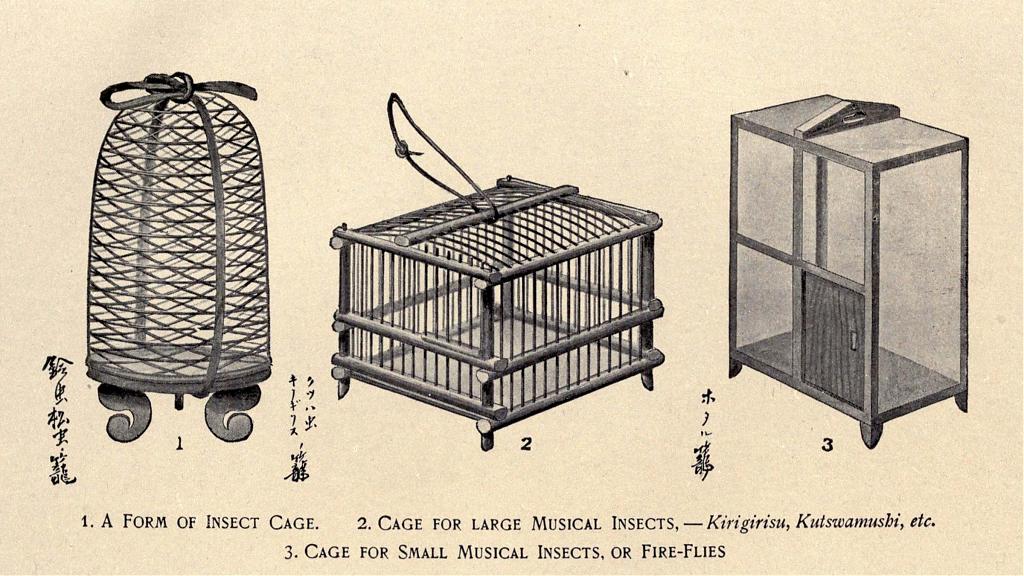

Edo’s insect vendors offered as many as twelve varieties of singing insects. Many carried also one or two quiet ones. Like the radiantly colored tamamushi (玉虫, jewel beetle) and the light-emitting hotaru (蛍, firefly). The 1920s edition of the popular travel guide Terry’s Guide to the Japanese Empire features an interesting description of customs associated with hotaru :9

At the firefly-shops the captured insects are sorted as soon as possible according to the brilliancy of their light (hotarubi) — which Japanese observers have described as cha-iro (tea-colored), because of its likeness to the clear, greenish-yellow tint of the infusion of Japanese tea of good quality… They are then put into gauze-covered boxes or cages (hotarukago) of one or two hundred each (according to grade) along with a quantity of moistened grass. Great numbers are ordered for display at evening parties in the summer season… In certain of the well-known tea-houses of Kyōto, Ōsaka and Tōkyō, a myriad of the delicate insects are kept in garden plots enclosed by mosquito-netting; customers of the houses are permitted to enter the inclosure and capture a certain number of fireflies to take home with them.

Japan’s insect business continued to flourish well into the early Showa period (1926–1989), but it gradually declined during the war years of the 1930s and 1940s.

There are still countless insect shops today, but the colorful insect vendors have long vanished from the country’s streets. And although insects are still popular pets, very few people now have cages with singing insects at home.

Notes

1 The Japan Times. What’s a Japanese summer without the noisy cicada? Retrieved on 2022-08-30.

2 Murasaki Shikibu, Seidensticker, Edward (1976). The tale of Genji Volume 1. Tokyo, Rutland, Singapore: Tuttle Publishing, 462.

3 Hearn, Lafcadio (1914). Exotics and retrospectives. Boston: Little, Brown and company, 43–44.

4 ibid, 46–47.

5 ibid, 45–46.

6 ibid, 49–50. Also the Nihon Shakai Jikishi (日本社会事彙, Japan Social Dictionary).

7 Hearn, Lafcadio (1914). Exotics and retrospectives. Boston: Little, Brown and company, 39–40.

8 ibid, 41–42.

9 Terry, T. Philip (1920). Terry’s Guide to the Japanese Empire Including Korea and Formosa. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 554.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 1890s: Selling Insect Musicians, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/903/insect-musicians-mushiuri-insect-vendors-vintage-albumen-print

There are currently no comments on this article.