A five-tiered doll display for hinamatsuri, the doll festival. In this photo from the 1890s the display already looks very similar to the ones that we are familiar with today.

The stand, known as a hina dan (ひな壇), is covered with a red carpet. The top tier features the male odairi-sama (御内裏様) and the female ohina-sama (御雛様).1 They are sitting in front of a screen and are flanked by a pair of lanterns. The male doll sits on the right, the seat of honor in the Kyoto palace.

Because dairi means imperial palace, the top dolls are often seen as representing an emperor and empress. But, originally they represented the aristocracy of the Heian period (794 to 1185).

On the next tier are three ladies (三人官女, sannin kanjo), ready to serve sake to the dairi-bina on the top stand. They are flanked by two ministers or guardians (随身, zuishin) with bow and arrow.

Below them are the gonin-bayashi (五人囃子), five musicians that make up a Noh theater orchestra: a singer, a flute player, and three drummers. The other dolls appear to be servants and gardeners.

These days, hinamatsuri displays always feature diamond-shaped tables with multi-colored mochi cakes. But these are absent in this display. There are also no oxcart, kago (palanquin), and food boxes (重箱, jūbako). There are however chests and dishes.

Hinamatsuri is one of five sekku, or seasonal festivals, that were influenced by Chinese philosophy. Known as gosekku (五節句), they were first observed by courtiers during the Heian period to ward off evil spirits. These sacred days fell on the first day of the first month, the third of the third, the fifth of the fifth, the seventh of the seventh, and the ninth of the ninth. On these days, rituals were held and special food was eaten to ensure good fortune.

The spring ritual was held on the first day of the snake (the sixth of the twelve signs of the Chinese zodiac). As this day was known as jōshi (上巳), the ritual was called Jōshi no Sekku (上巳の節句). This day was associated with peach blossom, so the ceremony also became known as Momo no Sekku (桃の節句). Courtiers would hold banquets by a winding stream that involved the writing of poetry. Interestingly, cockfights were held on this day as well.2

At this time, a belief had developed in Japan that human-like figurines made of straw, wood or paper could absorb evil influences and spiritual defilement known as kegare (穢れ). Dolls were placed next to a woman giving birth, given to children to protect them, and used as amulets. In some cases, people would stroke their body with dolls. Afterwards, the dolls were burned or set adrift on water.

This custom is described in The Tale of Genji, Murasaki Shikibu’s 11th century literary masterpiece about romance, palace intrigue, and poetry. On the third day of the third month, the protagonist Genji uses dolls for purification when exiled from court:3

The third month was now beginning and someone who was supposed to be well up in these matters reminded Genji that one in his circumstances would do well to perform the ceremony of Purification on the coming Festival Day. He loved exploring the coast and readily consented. It happened that a certain itinerant magician was then touring the province of Harima with no other apparatus than the crude back-scene [Zesho, a screen or in some cases curtain with a pine-tree painted on it; used as a background to sacred performances] before which he performed his incantations. Genji now sent for him and bade him perform the ceremony of Purification. Part of the ritual consisted in the loading of a little boat with a number of doll-like figures and letting it float out to sea. While he watched this, Genji recited the poem: ‘How like these puppets am I too cast out to dwell amid the unportioned fallows of the mighty sea.’ These verses he recited standing out in the open with nothing but the wind and sky around him, and the magician, pausing to watch him, thought that he had never in his life encountered a creature of such beauty.

In places like Kyoto, Wakayama and Tottori, the custom of setting dolls adrift on boats can still be seen today. It is known as hina nagashi (雛流し).

Intriguingly, The Tale of Genji also mentions one of Genji’s love interests, Murasaki, playing with dolls as a young girl. This confirms that doll play (雛遊び, hina-asobi) already existed as an important pastime for children of aristocratic families in the 11th century.

Dolls actually play important recurring roles in this work as effigies in purification rituals, guardians of children, and as playthings for girls, illustrating the overlapping roles of dolls as sacred object, amulet, plaything and display element.

Over the centuries, these disparate spiritual and decorative aspects gradually fused. By the Muromachi period (1336-1568), doll talismans and play dolls were exchanged as gifts during the March festivities. But it took until the Edo period (1603–1868), before the hinamatsuri as we know it finally started to take shape.

An important impetus appears to have been the enthronement—at the tender age of five—of Empress Meishō (明正天皇, 1624–1696) in 1629 (Kan’ei 6). Her parents were Emperor Go-Mizunoo and Tokugawa Masako, the daughter of the second Tokugawa shōgun, Tokugawa Hidetada. Empress Meishō’s uncle, Shōgun Iemitsu, sent her a large number of dolls for the March festival.

In 1644 (Kan’ei 21), lemitsu’s daughter, Chiyo-hime, received dolls for her birthday, which happened to fall on March 3rd. It now became increasingly fashionable to give dolls and lacquered accessories to girls to help them celebrate Jōshi no Sekku.4

This could not have been timed better. The Edo period was a time of increasing prosperity, and merchants were accumulating enormous wealth. Using this wealth, they started to adopt the customs of the higher classes, including the display of dolls.

As a result, the festival turned into an elegant display of exquisite dolls and accessories created by the best craftsmen of Japan. These, increasingly specialized in a specific element of doll creation; like the making of wigs, heads, or clothing.

Soon, merchant families were competing with each other to have the most ostentatious doll display. This escalated to a point where the Shogunate in Edo (current Tokyo) felt compelled to issue sumptuary laws restricting doll displays in 1649 (Keian 2), and again in 1658 (Meireki 4).

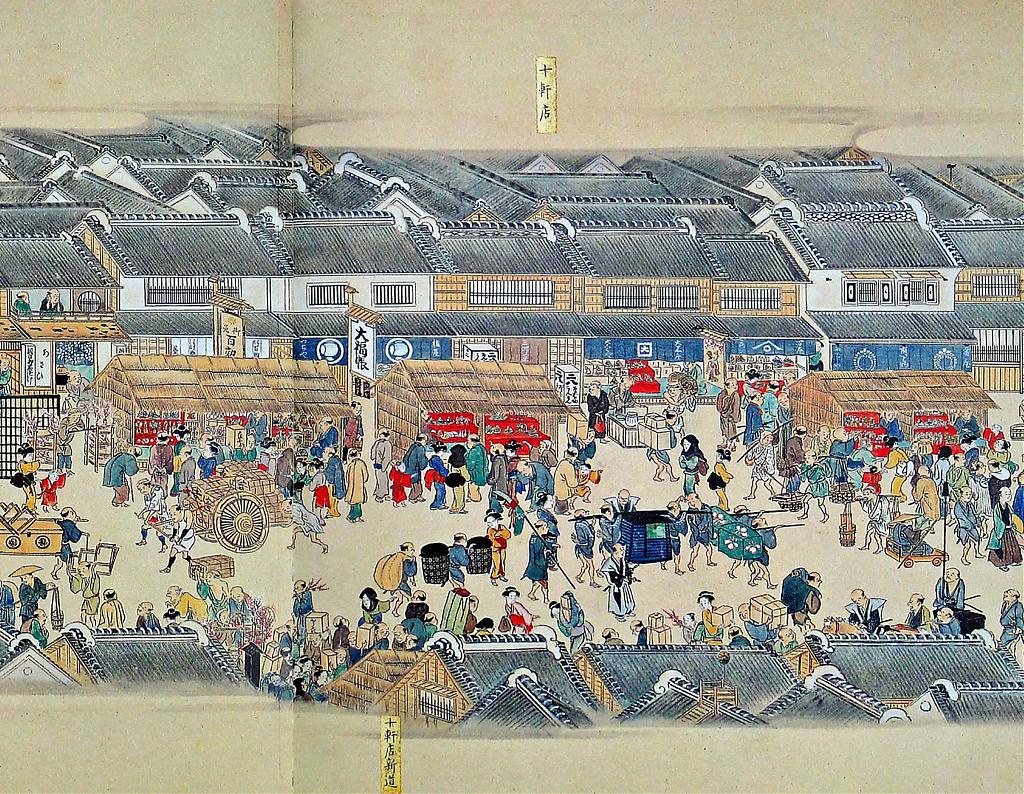

In 1687 (Jōkyō 4), the name of the festival was legally changed to hinamatsuri,5 and by the late 17th century, Edo had specialized hina doll markets. From February 27 to March 2, there were markets in Ginza ‘s Koji-machi (Owari-cho), Ningyo-cho, Takara-machi, Hongoku-cho and Jikkendana.

The Jikkendana market was so famous that it was featured in Edo Meisho Zue (江戸名所図会, Guide to famous Edo sites). From the 18th century on, hina doll markets were held in more and more places, and the starting date was advanced to February 25.

In addition to the shops and booths, there were hina doll vendors selling door-to-door, with boxes of doll clothes hanging on each end of a carrying pole. It was said that as the festival was approaching, the cries of the vendors could be heard all over Edo. This peaked during the 1760s and 1770s.6

The festival had now completely commercialized; the connections with its spiritual origins were forgotten. Just like people today complain that Christmas has been so commercialized that the true meaning of Christmas has been lost, Japanese in the 18th century were complaining about the commercialization of Jōshi no Sekku.

This rescue project is funded by readers like you

Old Photos of Japan provides thoroughly researched essays and rare images of daily life in old Japan free of charge and advertising. Most images have been acquired, scanned, and conserved to protect them for future generations.

I rely on readers like you to keep this project going.

Hinamatsuri Today

Somehow, the festival has managed to survive this commercialization, as well as the radical modernization and Westernization of the Meiji period (1868–1912), and the upheavals of the 20th century.

Hinamatsuri still is celebrated enthusiastically. Beginning in February, Japanese families with a daughter will set up impressive doll displays in their homes, which can these days be purchased as a codified set of fifteen dolls. Popular sets cost around 200,000 yen (USD 1,700+), but the most expensive ones can set you back over one million yen (USD 8,600+).

Unsurprisingly, the dolls are usually passed on from the mother to the daughter. In some families there are dolls that go back hundreds of years. To many Japanese women, the dolls carry an important meaning. They opened up a world of fantasy and dreams when they were children. While it is a tangible bond with the next and previous generations to mothers and grandmothers.

In the 1990s, I interviewed the then 72-year-old Yoshiko Ogino. She told me that even at her age she still got a warm feeling inside when the dolls came out of the boxes in February. As she brought back her memories, Yoshiko’s elderly voice sounded happy and young.7

As a little girl, hinamatsuri always made me very happy. My father was of the old school. He didn’t lift a finger at home. Not like the men of today who occasionally go into the kitchen or help with cleaning. My father did nothing. But hinamatsuri was traditionally the role of the father. On a day in early February, he would come home early from work. And then he very carefully took the dolls from the boxes one by one. That was very exciting. “Do the dolls still look good?” “Are there any bugs on them?” It was exciting every year. My father was very precise, so the dolls looked neat every year. He always took the emperor and empress out of the boxes first, and then the other things one by one. When he displayed the paper cherry blossom branches, it was as if spring had suddenly blown in. Last but not least, he turned on the lights in the lanterns and I walked into a dream world. The climax was March 3. My mother made sushi, I invited all my friends, and we ate in front of the dolls. Every year, this was a very special day for me.

Unfortunately her dolls did not survive the Second World War. Yoshiko was unable to pass the dolls on to her daughter Mineko.

We had to buy everything again for Mineko. We were very young and couldn’t buy it all at once. Every year we bought something new. First the emperor and empress, then one of the royal household, then the lanterns. All in all, it took about ten years to collect everything. We lived in Kyoto at the time and bought it at a very famous doll shop there. That was expensive! But every year when the dolls are on display I think, oh how beautiful! I feel very happy and warm inside and it all brings back memories of when I was a little girl myself. I get a very tender feeling inside. The dolls look so sweet, too. They may not say anything, but they radiate a lot of love.

When Yoshiko’s granddaughter was born, there was an extra dimension to celebrating hinamatsuri. Three generations lived together and hinamatsuri became a golden time for her.

When I interviewed Yoshiko, her granddaughter was already twenty years old, but the dolls were still unpacked every February. “There is an old saying,” she explained, “that anything with a face should see the light of day at least once a year.”

The dolls are packed the very day after March 3. People believe that leaving them out too long will affect the daughter’s marriage prospects. She will marry late, or may never get married at all.

Notes

1 The dolls on the top stand are also called obina (男雛, male hina) and mebina (女雛, female hina), tono (殿, lord) and hime (姫, princess), or tennou (天皇, emperor) and kōgō (皇后, empress).

2 Judy Shoaf, University of Florida College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Hina. Retrieved on 2022-03-02.

3 Waley, Arthur (1976). The Tale of Genji, A Novel in Six Parts by by Lady Murasaki, Volume One. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 253.

4 Pate, Alan (1998). The Hina Matsuri: A Living Tradition. Daruma Magazine #17.

5 Wikipedia: Hinamatsuri. Retrieved on 2022-03-02.

6 Kyugetsu Co., Ltd. History and Tradition of Dolls. Retrieved on 2022-03-02.

7 Duits, Kjeld (2002). Vrouw breekt los. ‘s-Gravenhage: Uitgeverij BZZTôH, 42.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 1890s: The Secret Powers of the Japanese Doll, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on February 22, 2026 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/885/japanese-doll-festival-hinamatsuri-vintage-albumen-photographs

Ilshat Khusnutdinov

There is a hinamatsuri on display in the Kunstkamera Museum (St. Petersburg). Male odairisama sits on the left. I don’t quite understand what this means.

P.S. Am I not overusing comments too much?

#000840 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

@Ilshat Khusnutdinov: I have not done any research on this, but the placement appears to differ by family and region. In the Kansai region the male generally sits on the right, while in Kantō he usually sits on the left, as seen from the viewer’s perspective.

You are not overusing the comments. I will try to respond as quickly as possible.

#000841 ·