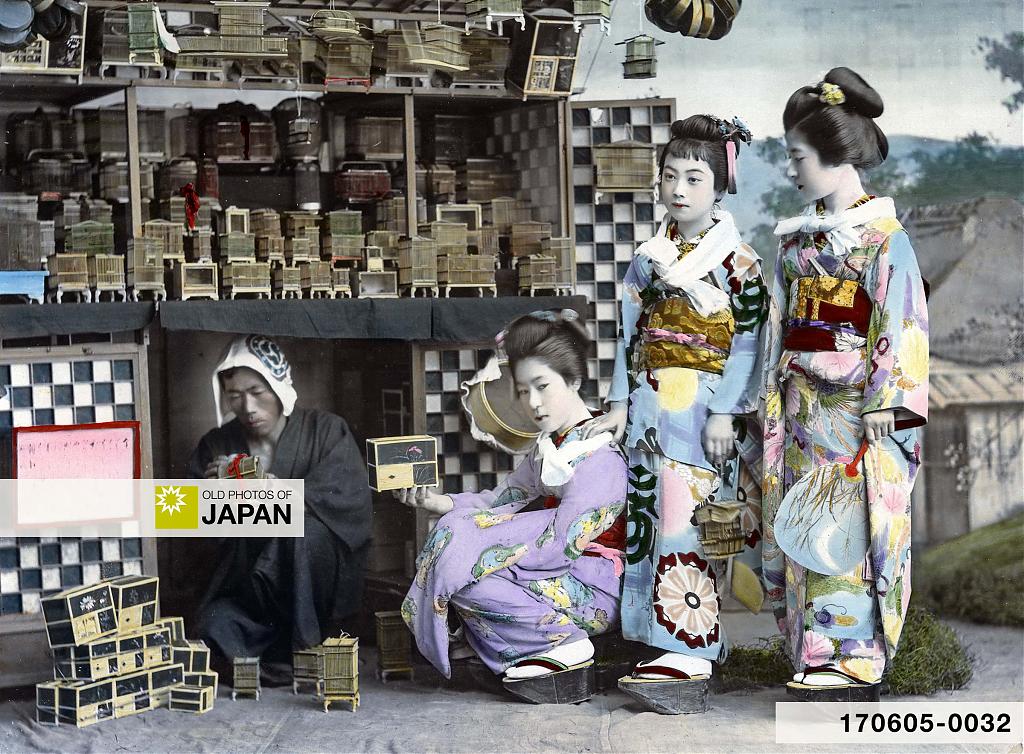

Children admiring the merchandise of a goldfish vendor. From the Edo period (1603–1867) on, street vendors were essential in daily life in Japan. They sold everything from vegetables to gold fish, fireflies and crickets. Even massages and medicine.

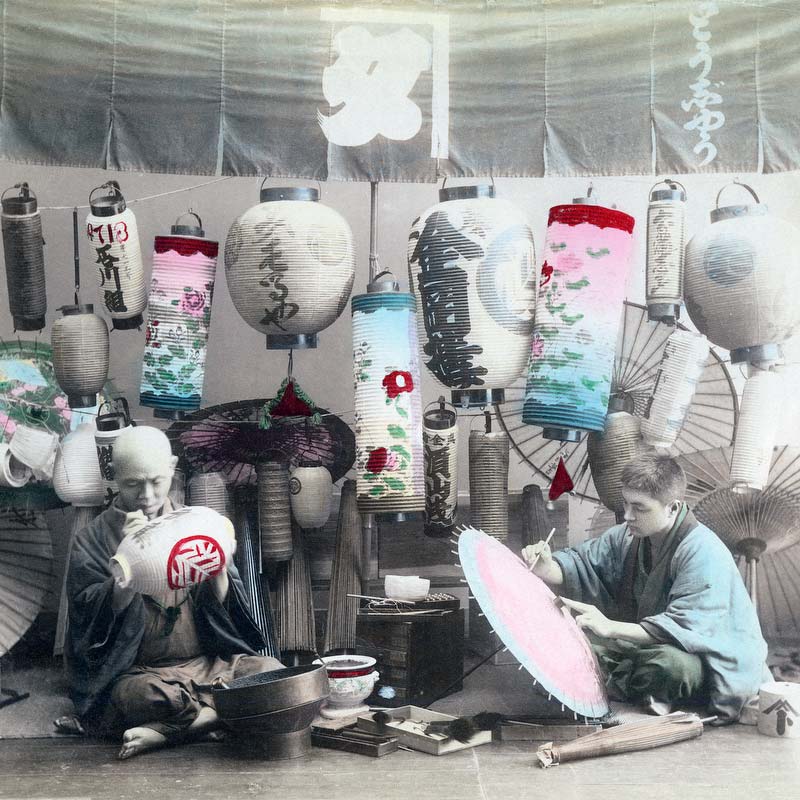

In old Japan, the streets were swarming with street vendors, known as botefuri (棒手振), each with a distinctive call that could be recognized from afar. Blind masseurs used a whistle.

In Glimpses of unfamiliar Japan, Greek-Japanese author Lafcadio Hearn (1850–1904), who made Japan his home from 1890 (Meiji 23), wrote how he was awakened by the sounds of a rice cleaner using a “colossal wooden mallet,” followed by the bells of Buddhist temples, and then vendors starting their rounds:1

Then the boom of the great bell of Tokoji, the Zen-shū temple, shakes over the town; then come melancholy echoes of drumming from the tiny little temple of Jizo in the street Zaimokucho, near my house, signaling the Buddhist hour of morning prayer. And finally the cries of the earliest itinerant venders [sic] begin, — “Daikoyai! kahuya-kahu !’‘ — the sellers of daikon and other strange vegetables. ‘‘Moyaya-moya !” — the plaintive call of the women who sell little thin slips of kindling-wood for the lighting of charcoal fires.

Unique System

When licenses were issued in 1659, Edo alone counted some 5,900 official vendors. This figure was almost certainly substantially higher, as there must have been countless unlicensed vendors trying to avoid paying taxes.

It was an easy job to get. It required no skill, knowledge, land or guild membership. Potential botefuri just needed to go to a company that would lend them the pole, baskets, and money to buy the merchandise. They received brief instructions and a territory, and off they went.

At the end of the day, the botefuri repaid the loan with an interest rate of 2–3%. What was left over was their profit. Many botefuri managed to save up enough money to eventually set up their own business.

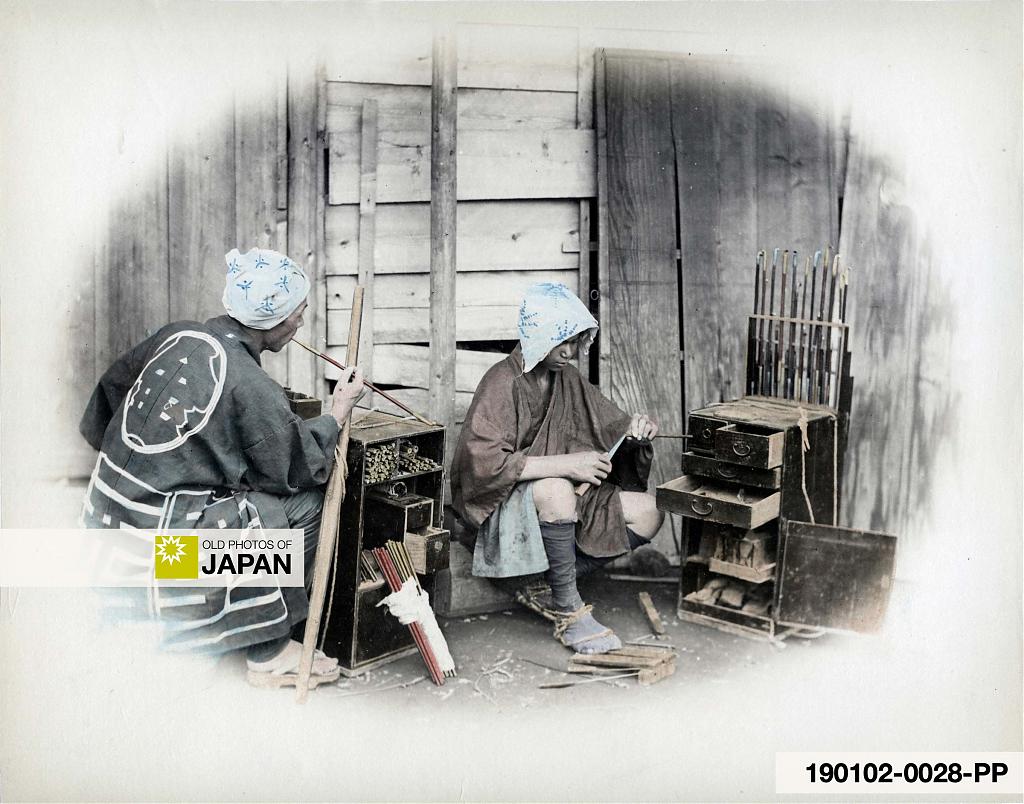

An especially innovative marketing system was used by companies selling medicine. Known as Toyama okigusuri, a vendor would leave a chest of over-the-counter medicine at a customer’s home on a use first, pay later basis. First started some 300 years ago, the system is still in use today.

The botefuri and tradesmen didn’t just walk the streets. Vendors would generally go to a back entrance, or enter the kitchen to ask for orders. It was pretty common to find an unexpected visitor in the kitchen.

In Home life in Tokyo (1910), Japanese author Jukichi Inouye described how often the vendors would visit:2

Those whose bills are settled at the end of the month are usually the dealers in rice, sake, and faggot and charcoal, the fishmonger, and the greengrocer. The rice-dealer does not call every day; he brings a bag of rice when required and knows pretty well when it will be exhausted. The sake-dealer comes every day; he sells, besides sake, soy, mirin, and miso; and in many cases he deals in faggot and charcoal as well. The fish-monger and the greengrocer call every morning ; the former will cook to order simple dishes of fish. Besides these regular tradesmen, there are street-vendors who bring bean-curd, boiled or steamed beans, and other food which will not keep long. We have no grocers properly-speaking in Japan; the nearest approach to them is the dealer in “dried vegetables.” Tea and sugar have, like rice, special dealers.

Although, street vendors mostly vanished after modern transportation took over Japan’s streets, every so often one can still hear the cry of a peddler today. Like the vendor of sweet potatoes with a recording screaming ishi-yaaaaki-imoooo, yaki-imoooo, yakitate — stone baked sweet potatoes, baked sweet potatoes, freshly baked!

Notes

1 Hearn, Lafcadio (1894). Glimpses of unfamiliar Japan. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 139–140.

2 Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 141–141.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 1910s: Have Fish, Will Travel, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on November 19, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/879/japanese-street-vendors-vintage-photographs

There are currently no comments on this article.