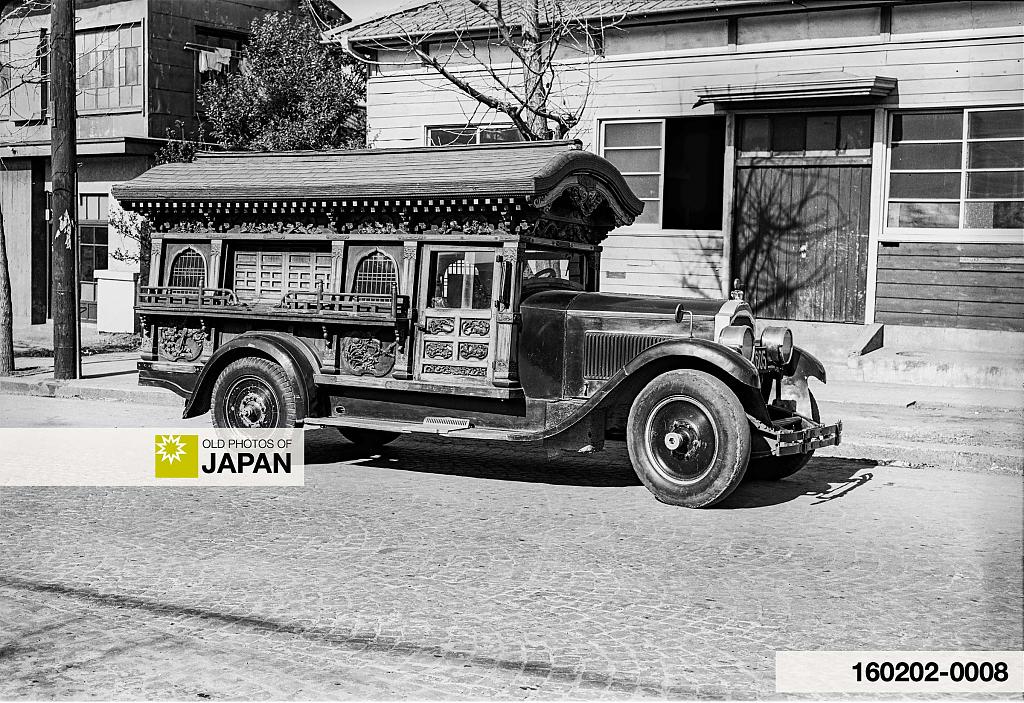

A huge funeral crowd has assembled around a hearse in a city that appears to be Tokyo or Osaka. The banner reads: “Kiku, the deceased mother of the Ishibashi family.“

Meiji Period (1868–1912) funeral processions were usually large and expensive affairs. It was said that two deaths within the same family over a short period of time could bankrupt that family. Criticism by social commentators and a rapidly changing society—especially cars pushing people off the streets—would eventually doom these ostentatious affairs.

Funeral customs differed greatly all over Japan, so it is impossible to give one description that fits all. This description will therefore limit itself to Tokyo funerals.

Starting in the Meiji Period a momentous transformation took place in the concept and management of Japanese funerals, the most important being the change from modest events that took place at night into huge public processions during the day, and the advent of funeral-industry workers (sogi gyosha). These changes originated in cities like Tokyo and eventually radiated out over the country.

Some changes lasted only for a few years, others through the Meiji Period. Yet others would survive to the present day.

A Meiji Period change in funeral customs that lasted only a short while was the ban on cremation, instituted in 1873 (Meiji 6). Authorities saw it as unfilial. But the prohibition didn’t take and was already repealed by 1875 (Meiji 8).

An important change that did last was a dramatic change in dress code. The color of mourning in Japan, as in most of Asia, had traditionally been white. Influenced by Western customs, it now became black. It still is today.

Another important change was that funerals became Buddhist affairs, whereas previously there had been many Shinto ceremonies.

The biggest change during the Meiji Period however was in size and display. Edo Period funerals in Tokyo, then still called Edo, had generally been modest and plain. Close family members usually transported the body of the deceased silently at night. This started to change during the late 1880s (Meiji 20s) when afternoon processions became increasingly popular.

As the strict hierarchy (mibunseido) of the Edo Period was undone, funerals grew into elaborate social events and funeral accessories changed significantly. Previously they were used only once, but now they could actually be rented. The result was that even common people could now have more elaborate funerals. As funerals became more public and grew in stature, accessories became increasingly colorful and beautiful.

Tokyo funerals had traditionally been managed by neighborhood funeral cooperatives called soshiki-gumi, but Meiji Period Tokyo saw the birth of funeral companies (sogisha). The word was actually first introduced in 1886 (Meiji 19) by Tokyo Sogisha (Tokyo Funeral Company). These companies provided the coffin, the altar, all the items used in the wake and the procession, and organized the workers.

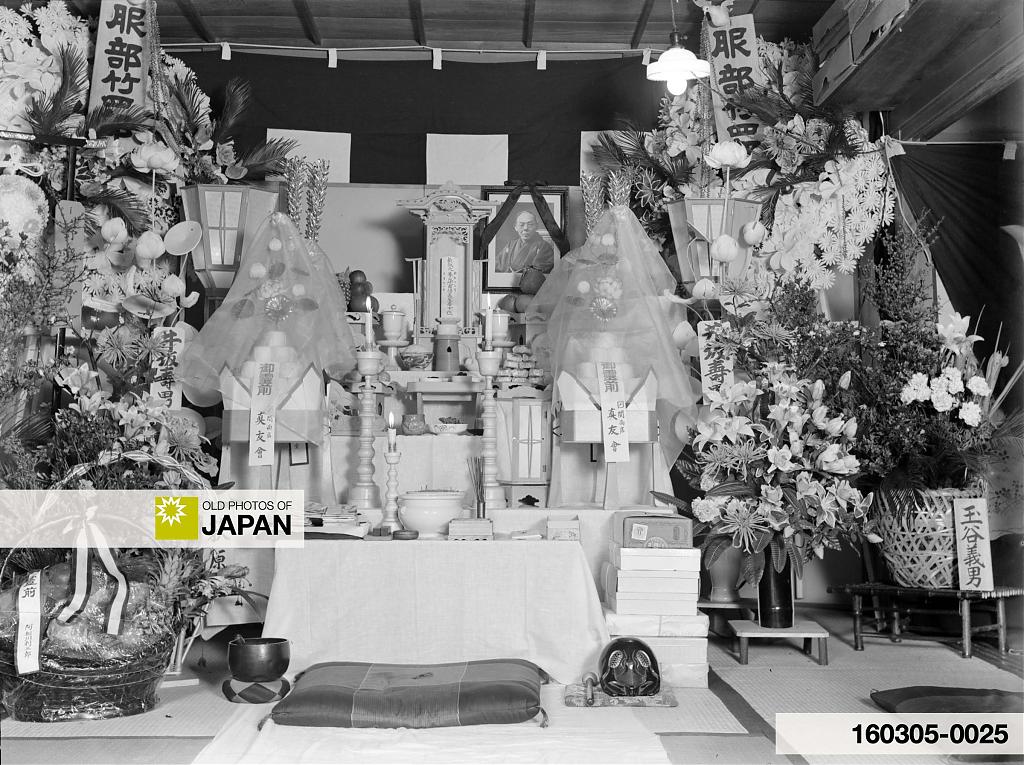

The funeral started with last rites (matsugo) and the placing of the body into the coffin (nokan). Neighbors and relatives selected someone from among their midst to take charge. Two hayatsukai went around informing the neighborhood, while sogiya prepared the coffin, the decorations and the cremation. During this private stage of the funeral, the body was dressed in death clothes (kyokatabira) and placed in the coffin by relatives. After an altar had been set up, a buddhist priest arrived and chanted makuragyo (pillow or bedside sutra).

The wake (tsuya) was attended by both relatives and neighbors, but rarely by others. These so called zen-tsuya or maru-tsuya (full wakes) lasted all night. Although rituals varied widely according to religious affiliation, they were usually lively affairs with food and sake.

The following morning, the procession generally left for the temple around 10:00 o’clock. Coolies provided by the sogiya carried the palanquin and the coffin. They were preceded by male relatives in formal clothing carrying, in this order, lanterns, flowers, birds that were later released (放鳥, hocho), incense burners and the memorial tablet, which was carried by the male heir. Women are said to have followed the procession in rickshaws, although this photo appears to contradict that.

Once arrived at the temple, the memorial tablet, incense, food, flowers and other items were placed on an altar. First, family members, seated separately, offered incense. Guests followed. At this time, everybody received sweets, some of them in the shape of lotus flowers.

After the funeral was finished, family members and sogisha employees carried the coffin to the location of the cremation. After burial within the city was prohibited in 1891 (Meiji 24), this often involved walking great distances.

Firewood created weak fires so cremations were very smelly affairs. As a result they were performed at night. The remains were picked up by the family the following day.

While village funerals were generally only open to the people of the village, funerals of Meiji Period Tokyo were arranged in such a way that as many people as possible could attend.1

Notes

1 Murakami, Kokyo (2000). Changes in Japanese Urban Funeral Customs during the Twentieth Century (pdf). Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 27/3-4 (Translated from: Sogi shikkosha no hensen to shi no imizuke no henka from Sosai Bukkyo; Sono rekishi to gendaiteki kadai, Ito and Fujii 1997: 97-122). Retrieved on 2008-05-01.

2 A Witness to History: Photo Album of the Funeral of Teru Araki features rare photos of a complete funeral, including the scene at the family home.

3 Recommended reading: Modern Passings: Death Rites, Politics, and Social Change in Imperial Japan.

4 Recommended reading: JETRO Japan Economic Monthly, February 2006. Trends in the Japanese Funeral Industry (pdf). Retrieved on 2008-05-01.

5 Many thanks to Rob Oechsle for helping to attribute this image to Kimbei Kusakabe.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 1890s: Meiji Funeral, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on February 22, 2026 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/169/meiji-funeral

There are currently no comments on this article.