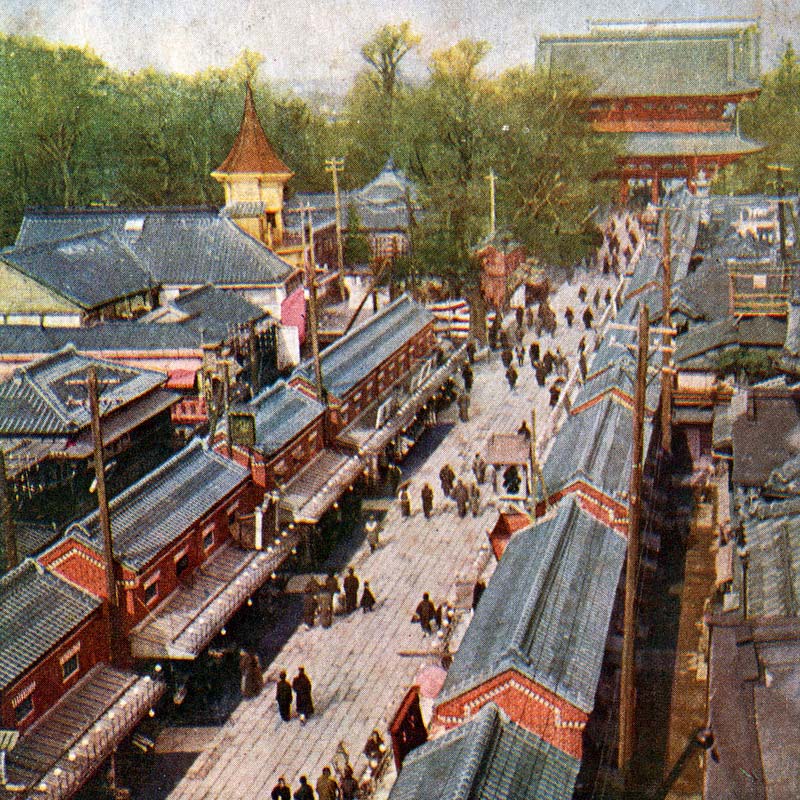

A Japanese confectionery shop offering a wide variety of mouth-watering sweets. Notice the space in front of the display boxes. Customers sat here while being served.

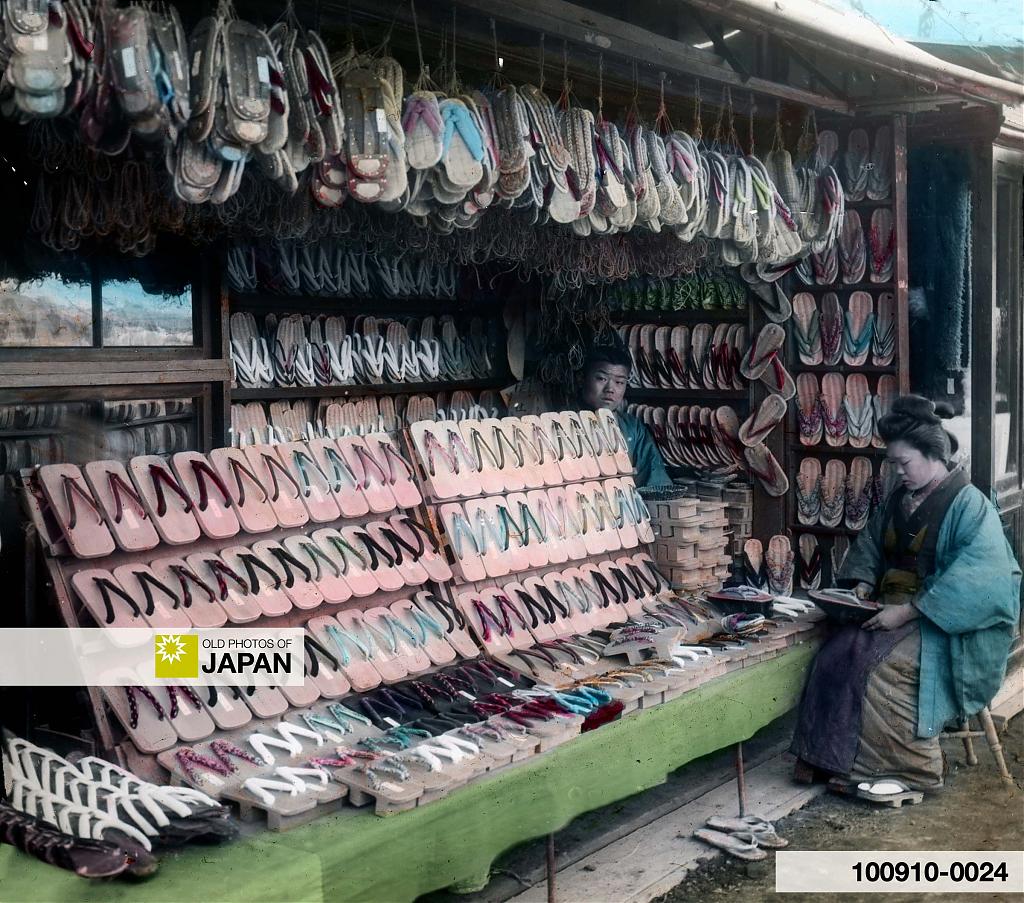

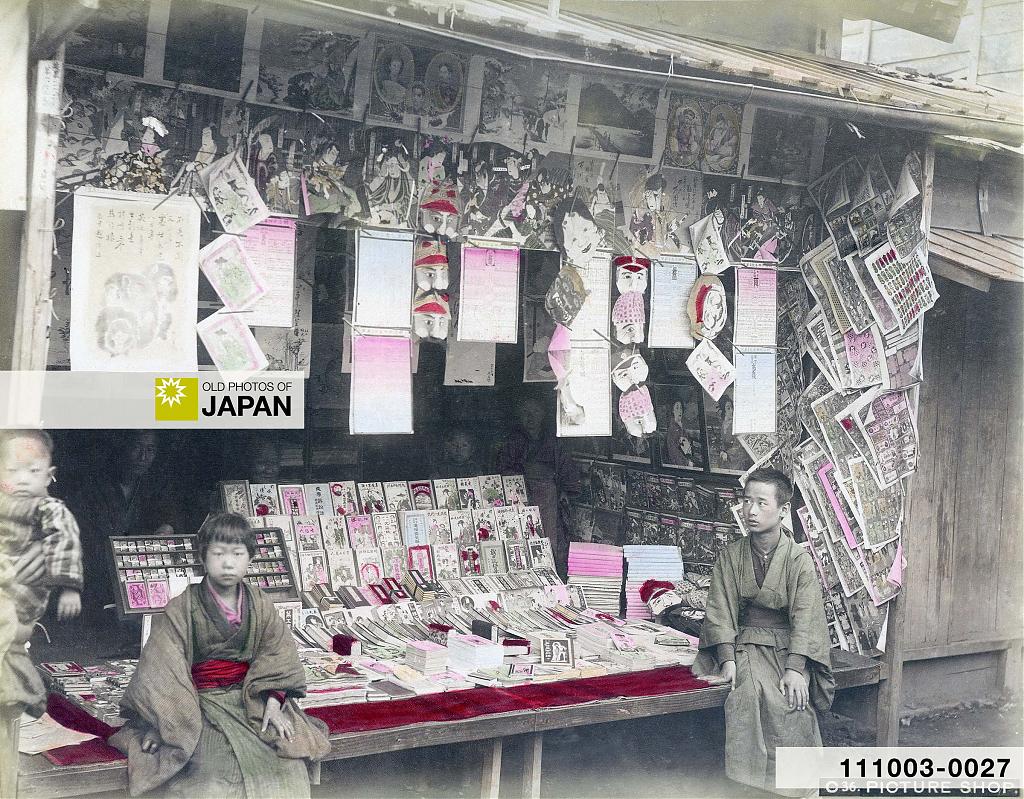

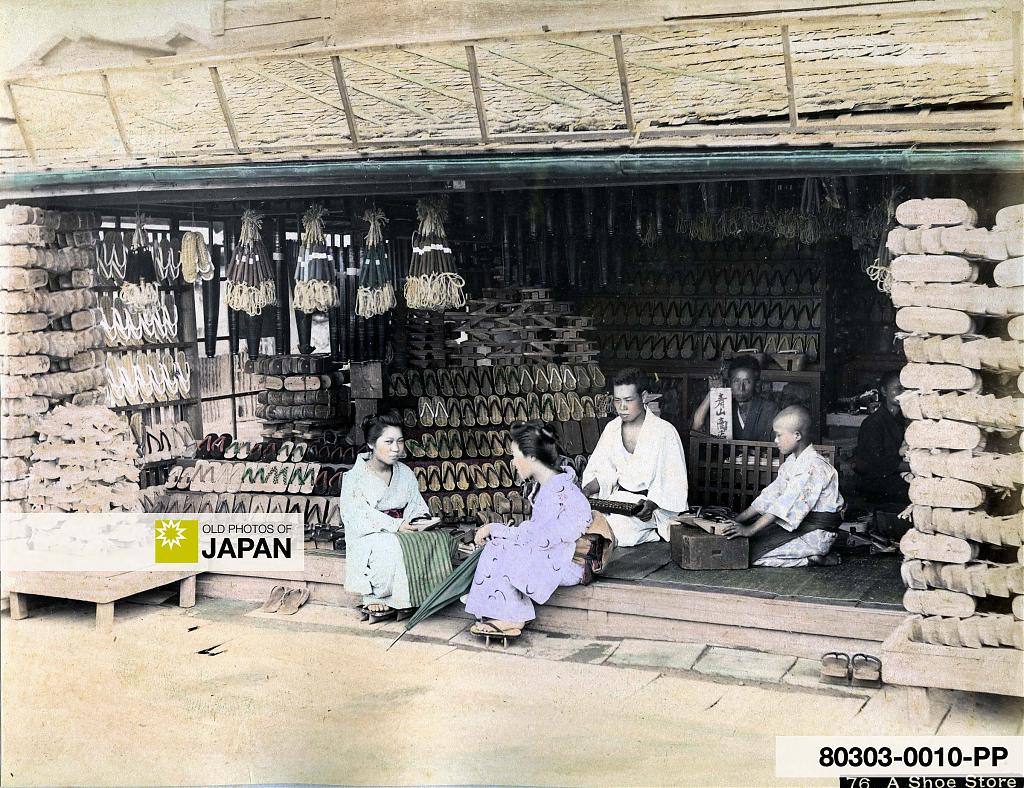

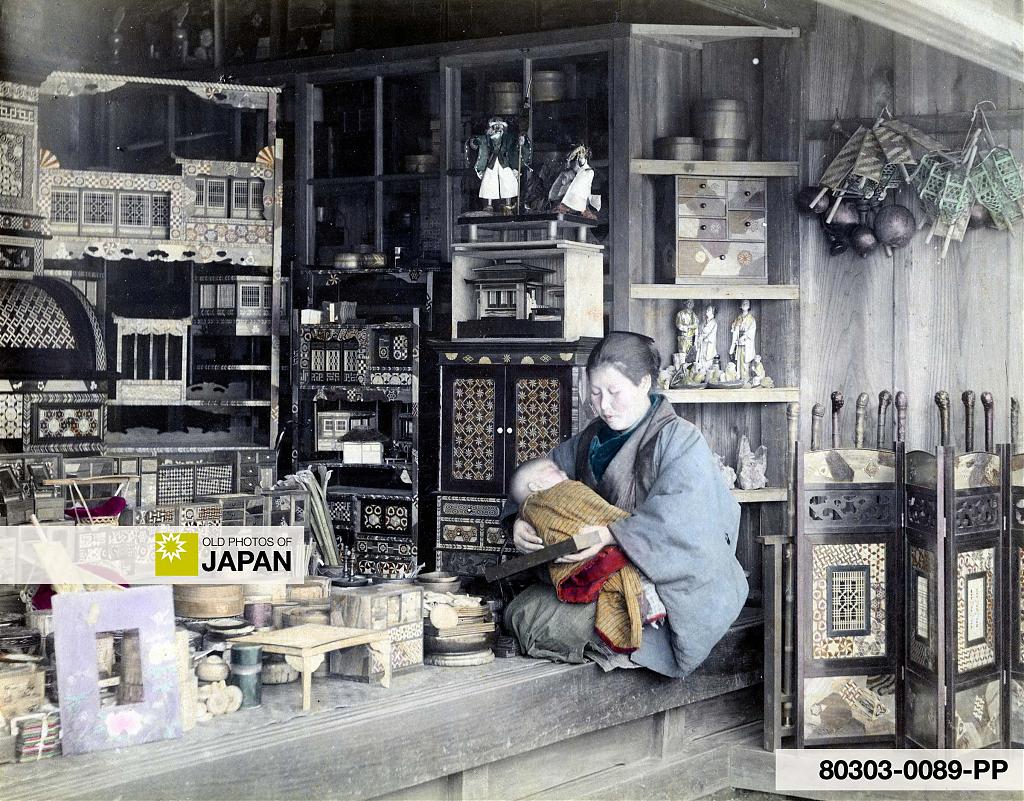

Even in the early 20th century, shop display windows were relatively rare in Japan. Many shops could not even be entered. They opened straight onto the street and displayed their goods on a raised platform, with some space left open for the customer to sit down. Often there were also chairs or stools.

The open store layout made streets lively, but also had its drawbacks. Japanese streets were not paved and were quite dusty. One could expect to get a serving of this dust with whatever was purchased.

Some shops employed kanban musume (看板娘, signboard girls), young women whose looks were expected to attract and persuade potential customers. They would sit or squat in front of the shop.

As would the owner’s wife, often with one of her babies in a sling on her shoulder. Perhaps boiling tea water on a bronze hibachi, shifting the embers about with brass tongs.

Goods were brought to the customer, instead of the customer going to the goods, as we are used to doing today. This made shopping personal, but also time-consuming. A visit to a shop could easily turn into a drawn-out affair with cups of tea and long chats.

Japanese author Jukichi Inouye describes such shops in Home Life in Tokyo:1

There are no streets in Tokyo which are known as fashionable afternoon resorts, because the shops are so constructed that one cannot stop before them without being accosted by the squatting salesmen. Only in a few main streets are there regular rows of shops with show-windows against which one could press one’s nose to look at the wares exhibited or peer beyond at the shop-girls at the counter; but then business is not done in Japan over the counter, nor do shop-girls hide their charms behind a window, for the shops are open to the street and the show-girls, or “signboard-girls” as we call them, squat at the edge visible to all passers-by and are as distinctive a feature of the shop as the signboard itself. The goods are exhibited on the floor in glass cases or in piles, a custom which is not commendable when pastry or confectionery is on sale, for standing as it does on the south-eastern end of the great plain of Musashino, Tokyo is a very windy city, and the thick clouds of fine dust raised by the wind on fair days cover every article exposed and penetrate through the joints of glass cases, so that in Tokyo a man who is fond of confectionery must expect to eat his pound of dirt not within a lifetime, but often in a few weeks. If one stops for a moment to look at the wares, he is bidden at once to sit on the floor and examine other articles which would be brought out for his inspection, whereupon he has either to accept the invitation or move on. One seldom cares therefore to loiter in the street. The only shops that are often crowded by loiterers are the booksellers’ and cheap-picture dealers’.

Have another good look at the top image. In the back, a young girl can be seen leaning on a small gate. This entrance most likely led to the living space of the family running the store. Generally, the living space behind the store was quite visible from the street. There were few barriers between street and family life.

Many foreign visitors were surprised by this lack of privacy and wrote about it in letters and books. One of the earliest foreign books to mention this in the 19th century was The Capital of the Tycoon, written by the first British diplomatic representative to live in Japan, Rutherford Alcock (1809–1897). He was stationed in the country between 1858 (Ansei 5) and 1864 (Bunkyū 4), just as Japan was opening its borders.2

One or two of the more salient features of Nagasaki street life must strike the least observant. I say ‘streetlife;’ but as all the shops have open fronts, and give a view right through the interior to the inevitable little garden at the back, and the inmates of the house sit, work, and play in full view, whatever may be the occupation in hand—the morning meal, the afternoon siesta, or the later ablutions, the household work of the women, the play of their nude progeny, or the trade and handicraft of the men—each house is converted into a microcosm where the Japanese may be studied in all their aspects.

Private life on display was not limited to shops. With living space generally at a premium, life in Japan’s town and villages would often spill into the streets.3

For the streets are always in the evening teeming with young children; they are not gutter-snipes, but children of respectable parents, small tradesmen or private persons of slender means, who let them run about on the public road rather than romp in their narrow dwellings. But it is not the children alone who think they have a greater right of way over the roads than the public; for on summer evenings especially, men and women turn out of doors and walk about or sit on benches outside their houses. Shops are completely open and reveal the rooms wthin, so that whole families may be seen from the streets; and as most houses are of only one or two stories, people live for the most part on the ground-floor.

Even as late as the fifties and sixties, much family life in Japan was played out on the streets. British sociologist Ronald Philip Dore, who studied a Tokyo neighborhood for several months during the 1950s, described this in his book City Life in Japan:4

Shitayama-cho may not present a very attractive exterior, and the sense of style and colour harmony for which the Japanese are justly famed may not be immediately visible, but Shitayama-cho was made to be lived in and not to be looked at. Its streets are lively and friendly places. In sunny weather they become playgrounds for groups of young children—boys with shaved or close-cropped heads, girls with doll-like fringes who sit outside their homes on rush mats (wooden clogs, as tabooed on outdoor mats as on the indoor ones, neatly lined up at the edge) banging merrily with a hammer at pieces of wood, making mud pies, entertaining with broken pieces of china on soap boxes, blowing bubbles, queueing for their turn on a lucky child’s tricycle. After school hours they are joined by groups of older children. Girls skipping or playing hop-scotch, ball-bouncing to interminable songs with a younger brother or sister nodding drowsily on their backs. Boys wrestling, poring over comics, huddled into conspiratorial groups, playing games of snap with tremendous gusto and noise. There is generally, too, a group of their mothers passing the time of the day as they look benevolently on and prepare to mediate in quarrels. With their hair permanently waved or drawn into a bun at the back and clogs on their feet (nothing else could be slipped on and off so easily every time they enter and leave the house), a white long-sleeved apron obscures the difference between those (younger ones) who wear skirt and blouse, and those (older ones) who wear kimono. One of them, perhaps, standing as she talks slightly bent forward to balance the weight of a three-year-old tied astraddle her back, is on her way to the bath-house, a fact proclaimed by the metal bowl she carries in hands clasped under the baby’s buttocks and by the washable rubber elephant with which he hammers abstractedly at the nape of her neck.

Notes

1 Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 17-18.

2 Alcock, Rutherford (1863). The Capital of The Tycoon: A Narrative of a Three Years’ Residence in Japan VOL. I. New York: The Bradley Company, Publishers, 90–91.

3 Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 12-14.

4 Dore, Ronald Philip (1958). City life in Japan : a study of a Tokyo ward. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 17.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 1890s: Japanese Sweets Shop, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on February 22, 2026 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/876/japanese-confectionery-shop-meiji-vintage-albumen-print-1890s

There are currently no comments on this article.