A Japanese firefighting crew (火消組, hikeshigumi) and their tools of the trade. Fires that destroyed whole towns were a common occurrence in old Japan. Over the centuries, countless methods were developed to fight them.

With buildings generally made of wood and paper, and many roofs using inflammable materials like thin shingles or thatch, fires could easily spread in Japan.

Edo (current Tokyo) was especially susceptible because of a combination of special conditions: seasons of dry weather and strong winds, a large population crowded into a dense urban area, and a high cost of living that caused severe poverty. The latter drove people to commit arson in order to loot in the following chaos.

Between 1601 (Keichō 6) and 1867 (Keiō 3), the city counted 1,798 fires, including 49 great fires that burned down large swatches of the city.

The situation turned especially bad after the administration of the Tokugawa shogunate became increasingly incapable between 1851 (Kaei 3) and 1867. In seventeen years, there were no less than 506 fires.

All these fires gave birth to the often quoted saying that “Fires and fights are the flowers of Edo” (火事と喧嘩は江戸の華, Kaji to kenka wa Edo no hana).

Here are a few selected “great fires” in Edo, and the number of people that were killed (taika means “great fire”).1

| Year | Name | Killed |

|---|---|---|

| 1657 | Meireki Taika | 107,000 |

| 1683 | Tenna Taika | 830–3,500 |

| 1772 | Meiwa Taika | 14,700 |

| 1829 | Bunsei Taika | 14,700 |

| 1855 | Earthquake Fire | 4,500–26,000 |

Fighting Fires

Unsurprisingly, Japan’s first fire service was already founded in 1629 (Kan’ei 6). Firefighting was institutionalized in Edo in the mid 17th century. Firefighters were classified into buke hikeshi (武家火消, samurai firefighters) and machibikeshi (町火消, townspeople firefighters). Edo’s firefighters were organized into 48 units, each with their own unique fire standard, known as a matoi (纏), in 1720 (Kyōhō 5).

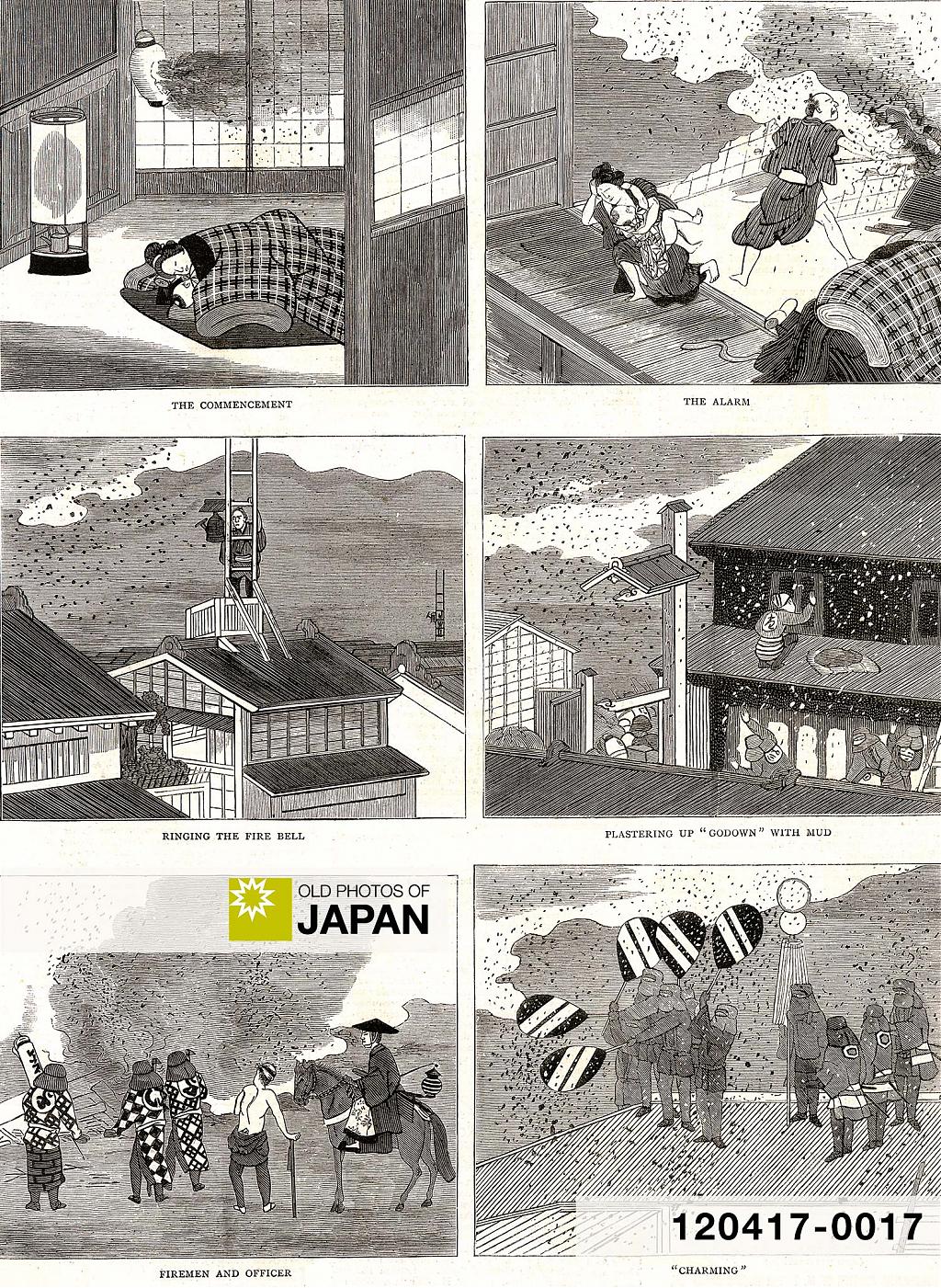

Firefighting equipment consisted of thickly wadded coats and helmets, special firefighting pikes known as tobiguchi (鳶口), long ladders, a portable wooden pump, as well as buckets, rope, and a long chain with hook for tearing down buildings.

To the amused surprise of many early foreign visitors, it also included lighted paper lanterns on long poles. This was however a basic need for moving groups of firefighters quickly through dark narrow alleyways.

The small wooden pump was not for fighting fires, but used mainly for keeping the firefighters wet. Instead of extinguishing fires, firefighters would tear down neighboring buildings to prevent the fire from spreading. As they came frightfully close to the fire while doing this, their crew members kept them wet.

Tearing down neighboring houses was actually the most efficient way of firefighting. Especially in crowded downtown Edo where many houses were rickety wooden affairs with shingled roofs that caught fire like kindling.

American zoologist and archaeologist Edward Sylvester Morse (1838–1925), who lived and worked in Japan during the late 1870s and early 1880s, wrote a lot about the many fires that he witnessed. He was initially extremely dismissive of Japanese firefighters, but later came to deeply respect them.2

The fact is that their houses are so frail that as soon as a fire starts it spreads with the greatest rapidity, and the main work of the firemen, aided by citizens, is in denuding a house of everything that can be stripped from it: partition-screens, floor mats, and the ceiling, which is of thin cedar board. It seems ridiculous to see them shoveling off the thick roofing tiles, the only fireproof covering the house has; but this is to enable them to tear off the roofing boards, and one observes that the fire then does not spring from rafter to rafter. The more one studies the subject the more one realizes that the first impressions of the fireman’s work are wrong, and a respect for his skill rapidly increases.

Alarm Bells

During the Edo Period, a warning system was set up using fire alarm bells, known as hanshō (半鐘). These were often hung on tall ladders, towers, on rooftop platforms or at open and high locations. As soon as a fire was detected, somebody climbed up and struck the hanshō with a stick. Morse found the “harsh and unmusical” sound “ridiculously feeble”.3 But there were so many of these hanshō, that nobody was out of earshot.

The way the bell was hit, indicated the rough location, the type of disaster, and even whether a fire was being extinguished. The hanshō nearest the fire was hit in rapid succession. Methods varied by area, and were later institutionalized by prefecture. In Tokyo this happened in 1903 (Meiji 36). It was adjusted in 1923 (Taisho 12).4

Because fires were so common in Tokyo, people seemed to have become a bit blasé about the alarms. Japanese author Jukichi Inouye mentions this in his book Home Life in Tokyo (1911).5

We are however, so used to the fire-alarm that if the peals are double to indicate that the fire is in the next district, we only get out of bed to look at it from idle curiosity and turn in again unless our house is leeward of the burning district or we have to run to the assistance of a friend there; and if the bell gives only single peals, which signify that at least one district intervenes between the burning street and the fire-lookout, we turn in our beds and perhaps picture to ourselves the lively time they must be having in that street.

Hanshō are still being made, and occasionally used today. They can mostly be found outside the large cities. They do not only warn people of fires, but also about disasters like flooding and tsunami.

For example, in 2019, the local fire department in Nagano City’s Naganuma beat four fire bells to wake inhabitants in the middle of the night. At the time, Typhoon Hagibis had caused record rainfall and the Chikuma River was about to burst its banks. “This is an old area, so to warn of danger, the hanshō is the easiest to understand,” said local fire chief Motohiro Iijima (飯島基弘) in an interview with Fuji News Network.6

The bells were also heard in many areas when the tsunami devastated northeastern Japan in 2011. In Otsuchi, Iwate Prefecture, one local firefighter tried to sound the siren when he was warned that the tsunami was rushing in. But there was no power anymore. He quickly took the hanshō out of the warehouse, and kept ringing it on the roof of the fire station until the tsunami took his life.7

Kura

To protect their valuables from fire damage, merchants built dozō (土蔵), large storehouses with thick plastered earthen walls and a tiled-roof. Popularly known as kura, they were used for merchandise, but also to store valuable personal belongings, like picture scrolls.

As soon as the alarm was heard, the few valuables in the house were quickly moved into the dozō. Usually, neighbors were able to place their items here as well. Before closing the thick door, a number of burning candles were placed at a safe spot. This would use up all the oxygen inside the kura and lower the chance of ignition.

After the doors were closed, the doors and windows were sealed with mud. This was kept in tubs, or in an underground storage area that could be accessed via a trap door.

The dozō were generally quite effective. On old photographs of the aftermath of fires they are usually the only buildings left standing. “After a great fire these black buildings tower up from the ruins, not unlike our chimneys under similar circumstances at home,” wrote Morse.8

Most people could not afford the expensive dozō. Instead they built wooden underground storage spaces, known as anagura (穴蔵, literally “hole kura”). They were often large enough to hold one or more persons, but were only used for valuable possessions that were placed here as soon as a fire alarm was heard. In Edo, they were mainly built with cypress, as it had high groundwater levels.

Fleeing

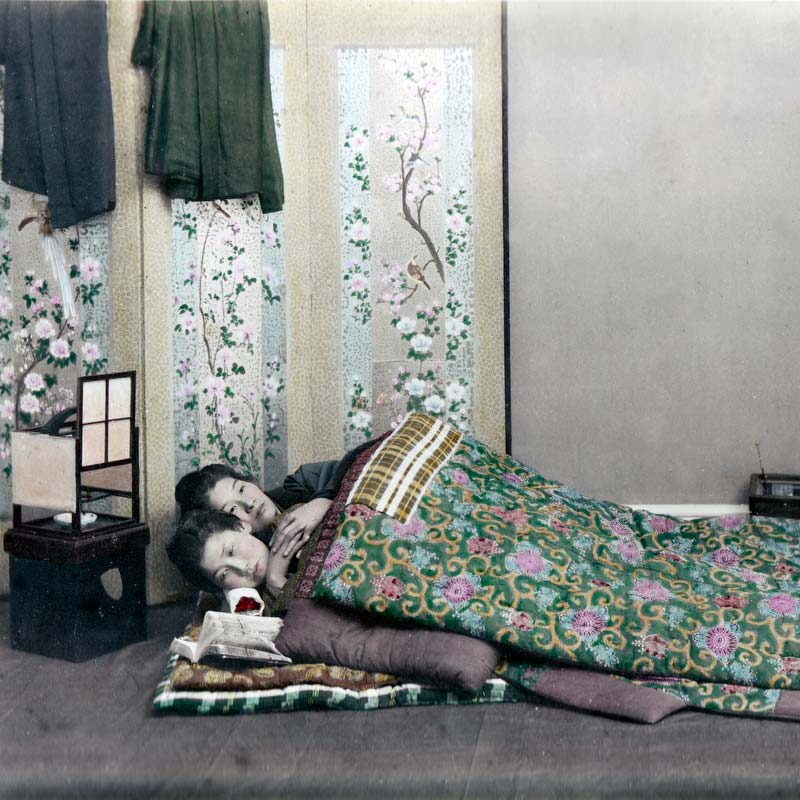

When Edo’s fire season approached in autumn, people started placing a kind of emergency kit next to their pillows before going to sleep. This included clothes, straw sandals and paper lanterns.

If the fire alarm announced a fire nearby, first the location and wind direction were checked. If the situation seemed dangerous, valuable articles would be put in the dozō or the anaguro, while portable belongings were loaded in carts, large bamboo baskets (用慎籠), wicker boxes (持退き葛籠) and from the 1870s on, rickshaws.

Portable is a flexible term here. Photos of people fleeing fires during the early 20th century, show closets, chests, screens and sliding doors.

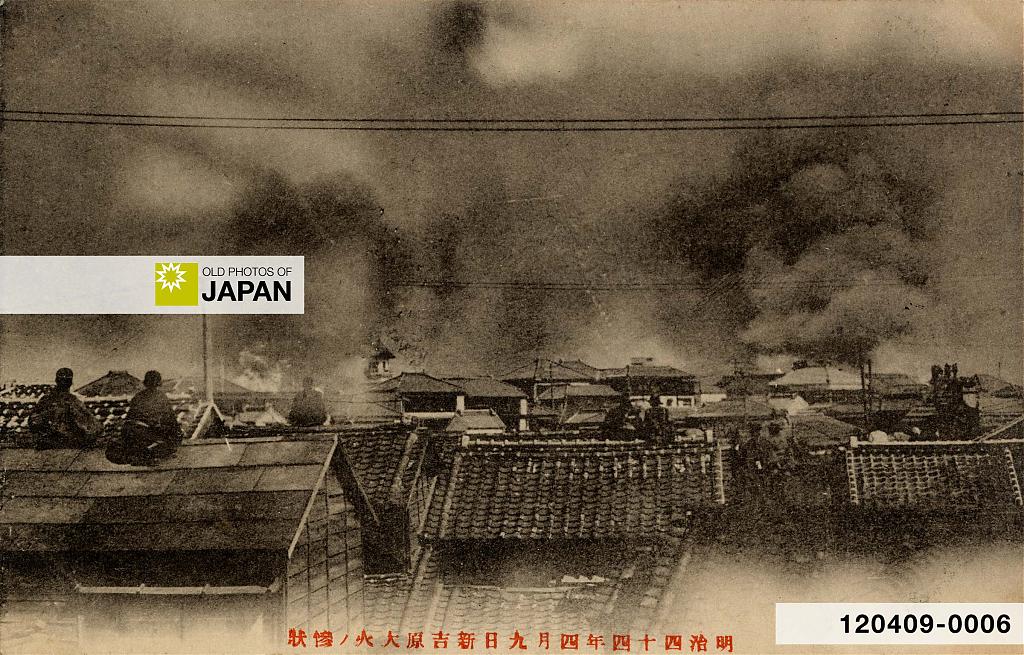

Before fleeing, people would first try to prevent the fire from spreading by climbing on the roof and putting out any sparks that landed there. Others climbed their roofs to watch the spectacle. Many contemporary accounts suggest that fires could be a bit like matsuri. People would walk long distances to get close.

In his biography, Yukichi Fukuzawa, the founder of Keio University, recalled how much fun he had during a fire he experienced in Osaka during the second half of the 1850s9:

Gradually we worked our way to the very edge of the fire. There were firemen pulling down houses with ropes tied to the pillars. The firemen asked us to help them, so we fell in and worked with the ropes among the burning houses. Then they gave us rice balls and wine. We worked, ate, and drank all we wanted. At about eight in the evening we came back to the dormitory. But the fire was still burning. Some of the more vigorous boys wanted to go back and have more fun.

Fukuzawa and his friends were no exceptions amongst academics. As his writings make clear, Morse also loved a great fire. He travelled long distances, often in a rickshaw, to get a good view. And just like Fukuzawa, he didn’t mind getting into the thick of it10:

At last I have had an opportunity of seeing a fair-sized conflagration, some sixty or seventy houses destroyed. Professor Smith, a tall Scotchman with reddish hair and whiskers, — a giant in fact, — came into my house at 10.30 at night and told me that a big fire was raging in the southern part of the city and asked me if I wanted to go. Of course I did, and off we went. We found a jinrikisha at the gate and, hiring two men, we started off at a rattling pace. The fire showed brightly above the low houses and now and then we passed a fireman running toward it. A half-hour’s ride brought us to a steep hill beyond which was the fire, so leaving the jinrikisha we ran up the steep and narrow lane and soon reached the crest of the hill, when the conflagration burst upon us in all its splendor. We had passed groups of people gathered about their scant belongings; patient old women with children on their backs, helpless infants on the backs of small children, men and women, all with smiles on their faces as if a festival were going on; during the whole night I never saw a tear or an impatient gesture or heard a cross word. Loud cries were heard at times when the standard-bearers stood in peril of their lives, but I did not see an expression of distress or concern. Smith and I rushed through hedges, over choice gardens, and through low houses that had been vacated until we reached a long street lined with houses on both sides, most of them in flames. I stood under overhanging eaves out of the way of falling tiles and watched the fight. The roofs of the long row of low houses were literally covered with firemen, working like heroes, tearing off the roofing tiles, shoveling off the light shingles, and pulling, cutting, and tearing apart the framework, while, blistered by the heat, several standard-bearers stood on the ridge-poles, saved from being consumed only by the streams of water more often thrown upon them and the firemen than upon the fire. A wide balcony which held four men engaged in their destructive work suddenly fell outward, and down they came into the street, with a crash, on burning timbers and hot tiles, while one of them fell inside the burning building. I thought, of course, that he was lost, but brave fellows rushed in and rescued him; shortly after he was carried by me a helpless lump, whether dead or not I did not learn. From this place Smith and I hurried off to another point, and here we took a hand in the fight. The efforts of the firemen in tearing down one low balcony were so futile that I could stand it no longer, and seizing a long beam I rushed in, tearing my coat and scratching my hands with the nails. No sooner was I exposed to the fire than a pipeman immediately directed his stream on me, and a muddy stream it was! I yelled to him to stop in as polite Japanese as I could muster out of my limited vocabulary; the pipeman smiled and directly turned the stream on Smith, who, if I mistake not, swore in Scotch. It was a satisfaction, however, to see the building go down by our united efforts. The amount of courage and misspent efforts displayed at these fires is amazing; with one tenth the courage and a little intelligent action a great deal more could be accomplished. The sight of the standard-bearers perched on the ridge-pole is ludicrous in the extreme. Courageous fellows they are, and often they lose their lives by remaining at their perilous posts too long. By this heroic conduct they inspire the members of their companies to deeds of bravery. I have understood also that when buildings upon which they stand are saved the fire companies represented by them receive a gift of money.

One of the most fascinating accounts of a large fire in old Japan is actually an emaki picture scroll, the Meguro Gyōninzaka Fire scroll (目黒行人坂火事絵巻, Meguro Gyōninzakakaji Emaki). It gives a pictorial view of the Great Meiwa Fire (Meiwa Taika), which destroyed much of Edo on April 1, 1772.

It is one of the three greatest fire disasters in Edo’s history. Some 14,700 people lost their lives. Be sure to click the link, scroll through, and study all the intricate details on each scan.

A far more simple pictorial view, but not less interesting, are these illustrations published in the British weekly illustrated newspaper The Graphic in 1878 (Meiji 11).

Fire Safety

These days, Japan’s fire safety is fairly high. The country generally has a fire death rate comparable with the average of the European Union, and significantly below that of the United States. Morse would be greatly impressed.

The following table compares the death rate per 100,000 inhabitants in 2019 for some selected countries.11

| Country | Rate |

|---|---|

| South Africa | 4.36 |

| Russia | 3.42 |

| India | 2.03 |

| World | 1.44 |

| G20 | 1.18 |

| United States | 0.82 |

| South Korea | 0.76 |

| China | 0.72 |

| European Union | 0.55 |

| France | 0.54 |

| Japan | 0.52 |

| Taiwan | 0.48 |

| Germany | 0.43 |

| United Kingdom | 0.38 |

| Australia | 0.31 |

| Singapore | 0.19 |

Additional Reading

Notes

1 Wikipedia, Fires in Edo. Retrieved on 2022-1-24.

2 Morse, Edward Sylvester (1917), Japan Day by Day, 1877, 1878-79, 1882-83. Volume II. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 126.

3 Morse, Edward Sylvester (1917), Japan Day by Day, 1877, 1878-79, 1882-83. Volume I. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 131.

4 ウィキペディア、概要。Retrieved on 2022-1-24.

5 Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 30-31.

6 Fuji News Network: 2019年10月20日、堤防決壊の夜に半鐘鳴らす 危険知らせ避難呼びかけ:「これは、ただごとじゃない。古い地域なので、危険を知らせるには半鐘が一番わかりやすい」Retrieved on 2022-01-23.

7 総務省消防庁。東日本大震災関連情報:災害の概要・消防団の被害。Retrieved on 2022-01-23.

8 Morse, Edward Sylvester (1917), Japan Day by Day, 1877, 1878-79, 1882-83. Volume I. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 31–32.

9 Fukuzawa, Yukichi (1972). The autobiography of Yukichi Fukuzawa. Schocken Books, 77-78. ISBN: 080520332X.

10 Morse, Edward Sylvester (1917), Japan Day by Day, 1877, 1878-79, 1882-83. Volume I. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 356–358.

11 Our World in Data. Deaths per 100,000 individuals. Retrieved on 2022-1-23.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 1880s: Japanese Firefighting, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/870/japanese-firefighting

There are currently no comments on this article.