An Ainu man with a boat on an otherwise empty beach.

Until the mid-nineteenth century, Japanese maps generally did not include the island of Hokkaido, then known as Ezo. Although it now constitutes some 21% of Japan’s total land mass, until the 19th century it was still seen by the Japanese as a mysterious foreign land inhabited by a savage people. These people were the Ainu, a distinct race with a unique culture and language.

By the 1830s, interaction and exploration had given the Japanese an increasing amount of knowledge about Ezo, which would soon be used to colonize the northern islands and subjugate the Ainu. By the end of the 19th century, the Ainu had become an ethnic minority—often discriminated against—in the Japanese state.

It was around this time, when a small yet increasing number of Westerners started to visit Hokkaido. Almost all of them were biased Western men, whose strong feeling of cultural superiority often made them extremely inattentive and inaccurate observers.

A partial exception perhaps was English painter, explorer, writer and anthropologist Arnold Henry Savage Landor (1865–1924), who visited the Ainu during an exploration in the late 19th century. Maybe because he was an artist he looked more attentively than most. Yet, he still thought nothing of writing “They are decidedly not moral, for nothing is immoral among them. The Ainu must be considered more as animals than as human beings.”1

In spite of remarks like these, which the modern reader will find painfully discriminatory, he did write some very detailed and interesting descriptions of Ainu culture. One such description is about the boats that the Ainu used2:

Prowling along the beach, I examined some of the Ainu canoes that had been drawn on shore. They might be divided into three classes—a ) the “dug-outs,” used mostly for river navigation; b ) the lashed canoe; and c ) a larger kind used for sailing. The “dug-out” does not require explanation, as everyone knows that it is a trunk of a tree hollowed out in the shape of a boat, and propelled either by paddling or punting. The lashed canoes are made of nine pieces of wood lashed together with the fibre of a kind of vine. The concave bottom is all of one piece—a partial “dug-out”—to which are added the side pieces, of three planks each, sewn together at an angle of about 170˚, and made to fit the sides of the “dug-out.” Two more pieces, one aft and one forward, meet the side planks at right angles. The length of these canoes varies from 10 to 15 feet, the width from 3 to 3½ feet. Two pieces of wood are then lashed horizontally, which answer the double purpose of strengthening the sides of the canoe and, being provided with pins outside the canoe, of allowing it to be used as an outrigger when rowing.

Canoes are either rowed or sailed. The oars are made of two pieces firmly lashed together. A hole is bored in the part which is to be passed through the pin in the outrigger. One person is generally sufficient to row an Ainu canoe, and he does so standing. The anchors used by the Ainu are very ingenious; they are cut out of a piece of wood, with either one or two barbs, and two stones are fastened on the sides of the stem so as to carry the anchor to the bottom. No compass is either known or used by the Ainu, and the natives shape their course by sight of land. They very seldom go long distances out at sea, as they are fully aware of the dangers of the ocean and of the imperfection of their own methods of navigation, though they are wholly incapable of making any improvements by their own judgment. The canoes are always beached when not used, and each family possesses its own. There are none which are the property of companies or are common to certain villages. There is no steering gear or rudder, and when rowing the oars are used for that purpose. Ainu canoes are not decked, and therefore cannot stand heavy seas. They are alike on both sides, and in most cases the two ends of the canoe are also shaped alike.

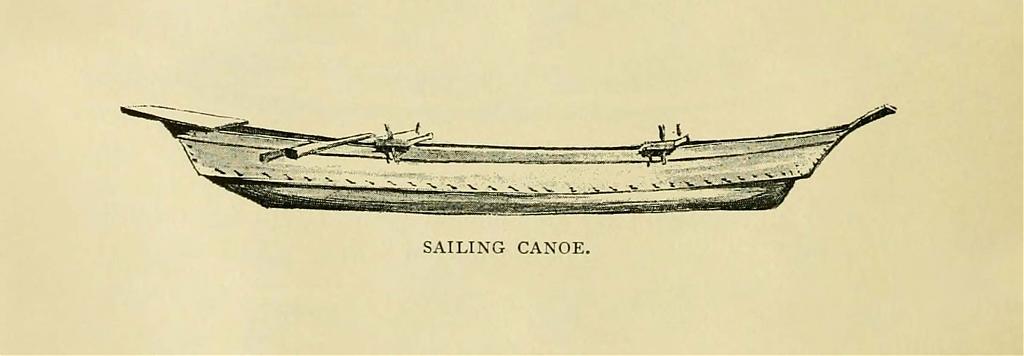

There are, however, certain canoes which, in my opinion, have been suggested to the Ainu by Japanese boats, and which are flat at the stern. These are generally larger, and used for sailing. A square mat sail is rigged on a short mast forward, and the steering is done with one of the oars at the stern. The sailing qualities of these canoes however, are not very great, and the slightest squall causes them to capsize and “turn turtle.”

Notes

1 Landor, Arnold Henry Savage (2001). Alone with the Hairy Ainu or, 3,800 Miles on a Pack Saddle in Yezo and a Cruise to the Kurile Islands. Facsimile reprint of the 1893 edition by John Murray, London. Adamant Media Corporation, 290. ISBN 9781402172656.

2 ibid, 37-39.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 1920s: Ainu with Boat, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/647/ainu-with-boat

Agata

Well, I would also add another exeption among Western expolorers – Bronisław Piłsudski. He lived among Ainu for some time and did outstanding research on their language, culture and customs. He also took photos of Ainu but these are extremely hard to find.

#000360 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

Yes, very good person to introduce, Agata. Thanks. I didn’t know him yet. I first confused him with the Hungarian Benedek Baráthosi Balogh, but when I checked I noticed I was mistaken. Balogh left a large collection of artifacts and photos of Ainu. I should try harder to include material from non-English sources. There were far more Chinese in Meiji Japan than other foreigners for example, but it is difficult to find Chinese source material if you don’t read Chinese, as little has been translated.

#000361 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

I just discovered that I did encounter his name before in a paper about Dutch encounters with Sakhalin and the Ainu people. Embarrassing, to so easily forget!

#000362 ·

Agata

On the other hand, I’ve never heard of Balogh. I’ve just read his short biography from the link above and I noticed a false statement: 1914 he first travelled to the Ainu in Japan then visited once more the Amur (…). This is of course not true because Piłsudski visited Ainu much earlier. Anyway I love his Ainu photo collection. Especially the photo with Ainu woman holding a western-style umbrella.

I mentioned Piłsudski because his is the #1 in Poland when it comes to Ainu. Some of his works have been translated into english by Alfred Majewicz.

#000363 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

With he first travelled they mean that he first went to one place before going to another place. It does not mean that he was the first. The Japanese were first of course.

#000364 ·

Agata

Ahh….now I get it :) I must’ve spent too much time in front of a computer if can’t read properly.

#000365 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

I have that problem, too! ;-)

#000366 ·