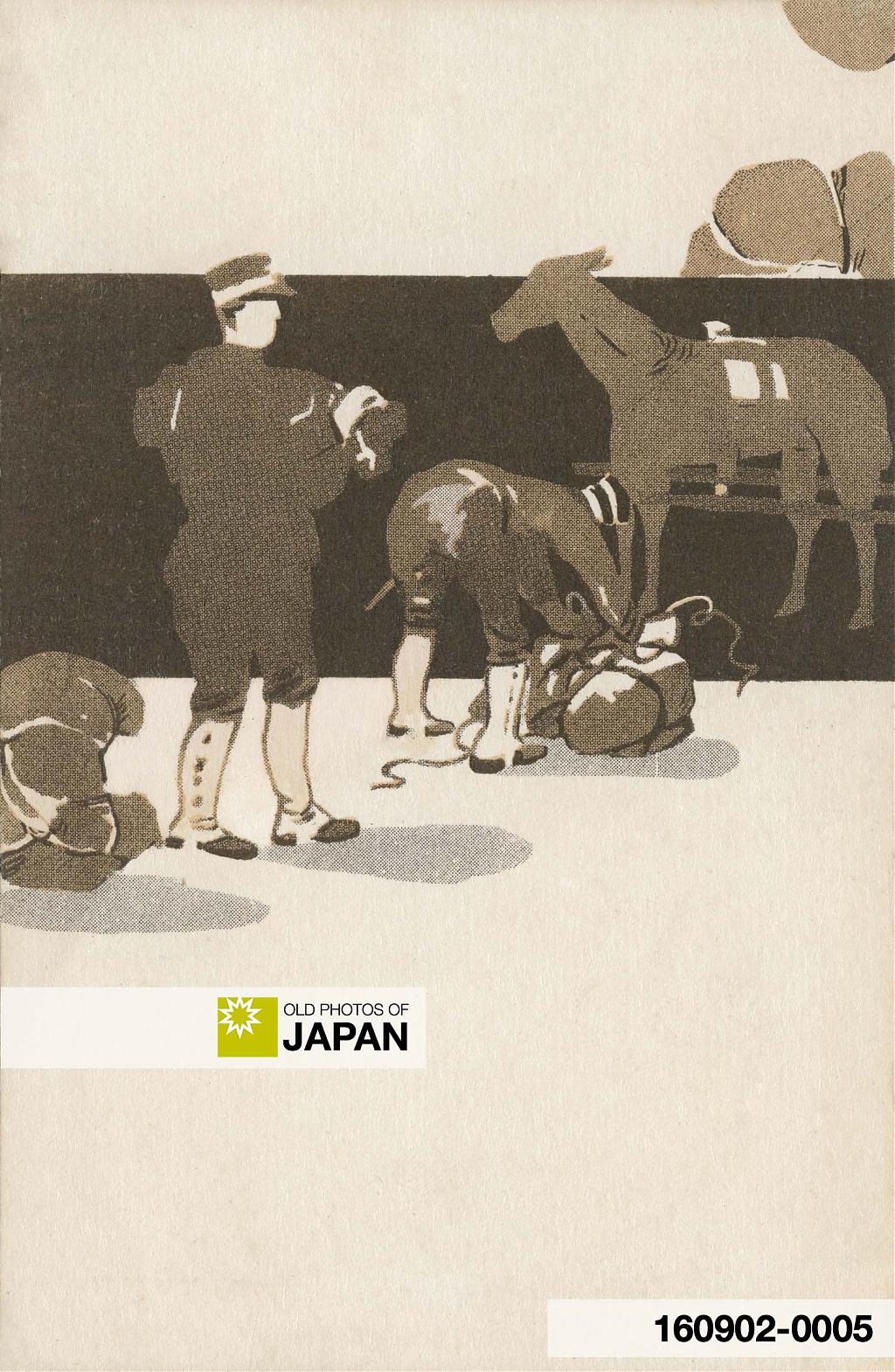

Imperial Japanese troops loading horses at Yokohama Port during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05). Japan deployed some 223,000 horses during the conflict.

Many did not even survive the sea journey from Japan to Korea. Either because of the cramped conditions and poor ventilation, or the storms they encountered. Horses can’t vomit and seasickness can kill them.

Some drowned upon arrival in Korea when they were transferred into small boats to take them ashore:1

Another boat loaded with baggage and horses capsized; one of the poor animals swam away toward the offing. The soldier in charge of the horse also swam to catch the animal. Before he reached it, the steed went down and soon afterward the faithful man also disappeared in the billows.

The toils of the journey were only the start. Once in the field, horses were often overworked, underfed and insufficiently cared for by soldiers unaccustomed to working with horses. The Japanese cavalry “saddled, bitted, and looked after their animals badly,” wrote the Austrian military observer Gustav Wrangel.2

American war correspondent Robert Lee Dunn (1874-1953)3 reported an encounter with a Japanese soldier riding a horse with a broken leg. “He had a Korean yanking the bridle and a Jap soldier beating the poor brute.”4

Countless horses succumbed to exhaustion, disease, and the wounds of battles.

The Russo-Japanese war was not the only time that Japanese horses went to war. Historians estimate that Japan mobilized 130,000 horses during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), while it sent half a million horses to war between 1931 and 1945 (Showa 6–20).5

In the half century that Japan waged war abroad, over 853,000 horses were pressed into war. Few returned home, they became dust in distant lands. Sadly, their suffering and ultimate sacrifice has been mostly forgotten and ignored in the annals and memorials of war.

Not everybody forgot them though. Many people who worked with these horses during wartime felt indebted to them. Japanese officer Tadayoshi Sakurai (桜井忠温, 1879-1965), who wrote a now classic memoir, Human Bullets: A Soldier’s Story of the Russo-Japanese War, was explicit about the important role that horses had played, and their sad fate.6

One of the most pitiful of sights is, perhaps, the dead or wounded war-horses. They had crossed the seas to run and gallop in a strange land among flying bullets and the roar of cannon. They seemed to think that this was the time to return their masters’ kindness in keeping them comfortable so long. With their masters on their backs they would run about so cheerfully and gallantly on the battle-field! The pack-horses also seemed proud and anxious to show their long-practiced ability in bearing heavy burdens or drawing heavy carts, without complaining of their untold sufferings. Their usefulness in war is beyond description. The successful issue of a battle is due first to the efforts of the brave men and officers, but we must not forget what we owe to the help of our faithful animals. And yet they are so modest of their merits; are contented with coarse fodder and muddy water; do not grumble at continual exposure to rain and snow, and think their master’s caress the best comfort they can have. Their manner of performing their important duties is almost equal to that of soldiers. But they are speechless; they cannot tell of wound or pain. Sometimes they cannot get medicine, or even a comforting pat. They writhe in agony and die unnoticed, with a sad neigh of farewell. Their bodies are not buried, but are left in the field for wolves and crows to feed upon, their big strong bones to be bleached in the wild storms of the wilderness. These loyal horses also are heroes who die a horrible death in the performance of duty; their memory ought to be held in respect and gratitude. My teacher, the Rev. Kwatsurin Nakabayashi, accompanied our army during the war as a volunteer nurse. While taking care of the wounded at the front, he collected fragments of shells to use in erecting an image of Bato-Kwanon [horse-headed kannon worshipped as a guardian Buddha of horses] to comfort the spirits of the horses that died in the war. This plan of his has already been carried out. Another Buddhist by the name of Doami has been urging an International Red Cross Treaty for horses such as there is now for men. Without such a provision he says we cannot claim to be true to the principles of humanity. Our talk of love and kindness to animals will be an empty sound. He is said to be agitating the introduction of such a proposition at the next Hague Conference. Of course there are veterinary surgeons in the army, but no one can expect them to be able to bestow all necessary care on the unfortunate animals. To supply this deficiency and protect animals as best we can, a Red Cross for horses is a proposal worthy of serious attention.

Although horses were used as late as the Second World War (1939–1945), the Russo-Japanese War made it crystal clear that the age of the war horse had irrevocably come to an end. Even pro-cavalry military observers at the time conceded that both the Russian and Japanese cavalry had been mostly useless on the modern battlefield.

The conflict has been called World War Zero because of the “newly developed capacity of industrialized powers to wage war on an unprecedented scale” and a “legacy that weighed heavily on world history.”7 Over 2.5 million men were mobilized and armed with the sophisticated mass-produced weapons of modern industry.

It thereby presaged the trench and fortification warfare, massive casualties, and global financing of WWI (1914-18). The Siege of Port Arthur, the longest and most violent land battle of the Russo-Japanese War, is often presented as a sort of test ground for Verdun, one of the longest battles of the First World War.

The large-scale industrialized warfare made cavalry tactics totally ineffective. Horses were helpless against automatic machine guns and steel-and-concrete fortifications surrounded by trenches, barbed wire and thoroughly mined no-man’s-land. Cavalry charges were no longer a viable offensive option. As a result, no large cavalry actions were fought, and the war marks the turning point in the history of cavalry.

Horses were however still perfect for a function like reconnaissance, noted Austrian military observer Gustav Wrangel. Even when both horse and rider were insufficiently trained:8

[The Japanese cavalryman] has proved himself to be an excellent scout and dispatch rider in spite of his want of good horsemanship and his slow and badly trained horse.

More importantly, horses were absolutely vital for transportation and supply, the role they would play as late as WWII.

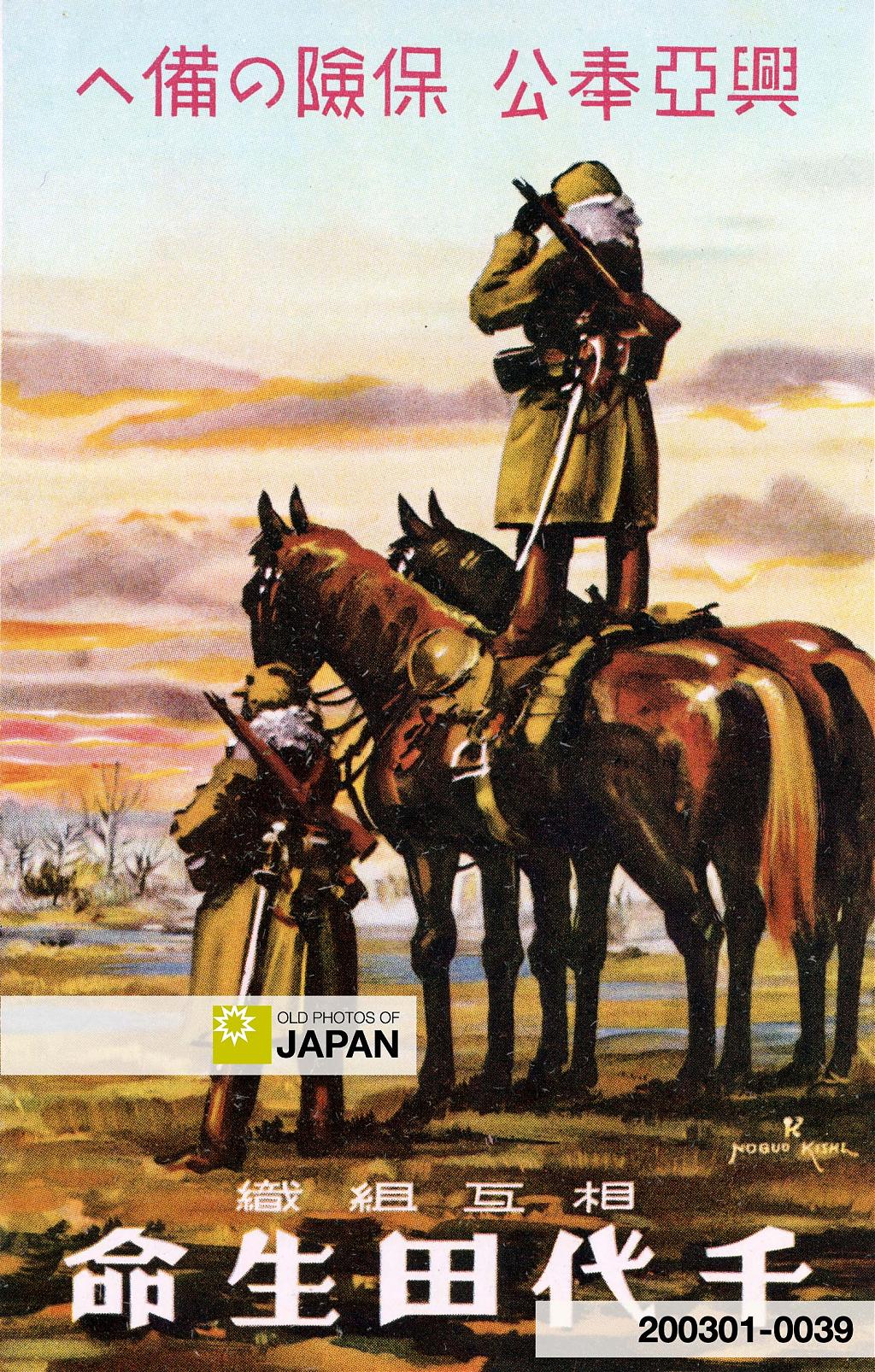

Horses had one more critical role: as agents of propaganda and nationalistic fervor. Because the army was unable to get enough horses, military horses were glorified to bolster the improvement of horses and encourage people to give them up for military service. This was a long-term program that only ended when the Second World War came to a close in 1945 (Showa 20).

Over the next decades, military horses became a popular theme in illustrations of war, greatly magnifying and glorifying their limited role in combat. Horses also featured in newspaper and magazine articles, songs, textbook stories, juvenile literature, films, monuments, parades and other public ceremonies.9

How deeply this propaganda program was embedded in daily life is illustrated by the 1940 movie Akatsuki ni Inoru (暁に祈る, Prayer at Dawn). The story revolves around a horse requisitioned by the army, a soldier on the front lines in China, and his wife on the home front. The movie aimed to raise awareness of the military and its horses.

The Horse Administration Division of Japan’s Ministry of War was deeply involved in the movie’s creation. At the time, it was lead by Tadamichi Kuribayashi who would later lead the defense of Iwo Jima. He became internationally known after being portrayed in Clint Eastwood’s 2006 film Letters from Iwo Jima.

The movie was incredibly popular and sprouted two popular songs, the title song and Aiba Hanayome (愛馬花嫁, Favorite Horse’s Bride’s Song). The lyrics were partly based on the victories achieved in the Russo-Japanese war. Both are actually anti-war songs, which might be why the U.S. War Department decided to re-release the film during the post-war occupation of Japan.

In 1931 (Showa 6), April 1 was designated to be a day to celebrate horses, Aiba no Hi (愛馬の日, Beloved Horse Day). It became a national event in 1939 (Showa 14) and was moved to April 7. Amongst other events, horses were paraded in large numbers, memorials for horses were held at temples, posters were displayed on buses and trains, NHK broadcast special horse programs on the radio, and pony races were held all over Japan.

Aiba no Hi was observed in the occupied territories as well. In Korea, the festivities were combined with prayer ceremonies for victory in battle.10

One propaganda flyer distributed during the 1930s by Tairiku Shinposha (大陸新報社), a China based newspaper controlled by the Japanese Imperial Army, encapsulated the message the government wanted to get across. It featured a smiling soldier gently holding his horse’s head and the text, “Thank you for your hard work, soldier. Please send my regards to your horse, too.”11

Although Aiba no Hi was discontinued after the end of WWII, a memorial statue of a military horse was dedicated at Yasukuni Shrine on April 7, 1958 (Showa 33). The nationalist shrine holds an annual ceremony for horses, dogs and pigeons that gave their lives to the nation.

All the propaganda had just one aim: to breed more and larger horses for warfare. As Japan’s eight domestic breeds were small, the rearing of these breeds was forbidden. Instead, large numbers of horses were imported from abroad, and breeders were encouraged to mix Western horse strains into the indigenous breeds.

As a result, Japanese horses were transformed dramatically. The program was actually so successful that domestic breeds nearly went extinct. Between 1905 (Meiji 38) and 1935 (Showa 10), the percentage of horses of Western or mixed breed rose from 12.2% to 96.6%.9

As result, Japan’s domestic breeds are now very rare. It is only thanks to organizations fighting for their survival that they are still around.

Hard to comprehend that over a century after the end of the Russo-Japanese War, its effects are still felt today.

Notes

1 Sakurai, Tadayoshi (1907). Human Bullets: A Soldier’s Story of Port Arthur. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 32.

2 Wrangel, Gustav (1907). The cavalry in the Russo-Japanese war. London: Hugh Rees, Ltd., 42.

3 Find a Grave: Robert Lee Dunn. Retrieved on 2022-01-31.

4 Dunn, Robert L. et al (1905). The Russo-Japanese War; a Photographic and Descriptive Review of The Great Conflict in The Far East. New York: P. F. Collier & Son: 58.

5 Skabelund, Aaron (2014). Memories of Japanese Military Horses of World War II. War Horses Conference @ SOAS 2014, 1–2.

6 Sakurai, Tadayoshi (1907). Human Bullets: A Soldier’s Story of Port Arthur. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 57–59.

7 Steinberg, John W. (January 2008). Re-Imagining Culture in the Russo-Japanese War: Was the Russo-Japanese War World War Zero?, The Russian Review Volume 67, Issue 1, 2-4.

8 Wrangel, Gustav (1907). The cavalry in the Russo-Japanese war. London: Hugh Rees, Ltd., 38–39.

9 Skabelund, Aaron (2014). Memories of Japanese Military Horses of World War II. War Horses Conference @ SOAS 2014, 2.

10 Veldkamp, Elmer (2008). Commemoration of dead animals in contemporary Korea : emergence and development of Dongmul Wiryeongje as modern folklore, The Review of Korean Studies Volume 11, Issue 3, 162.

11 Japan War Art: 1930’s Japanese Army Propaganda Flyer. 「御苦勞さまです兵隊さん。馬にもどうぞよろしくね。」Retrieved on 2022-01-31.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

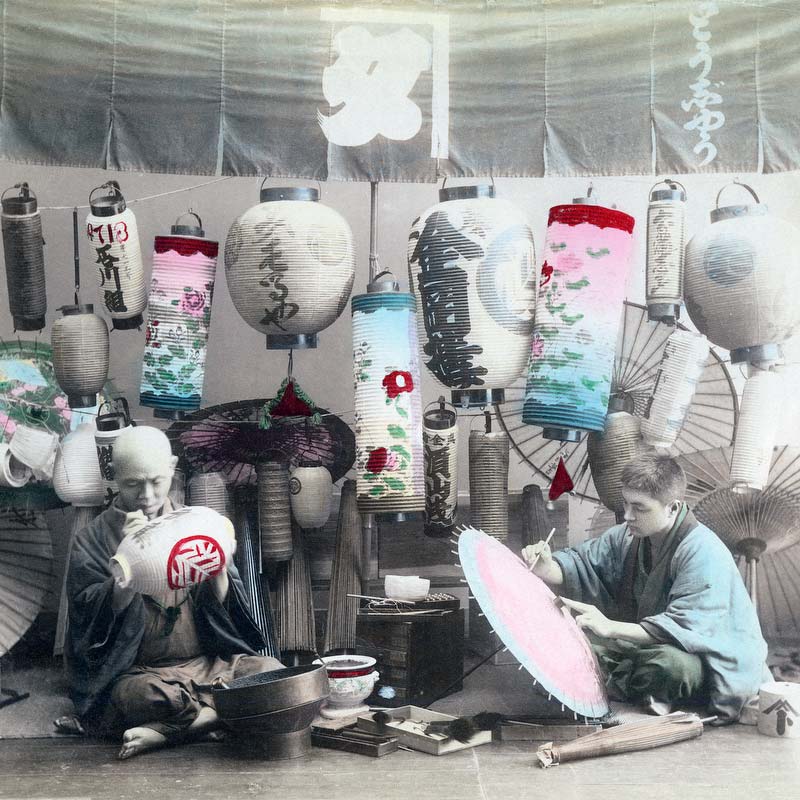

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Yokohama 1904–1905: Horses at War, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on November 19, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/874/japanese-war-horses-20th-century-russo-japanese-war

Anna Foden

Thank you for this article. It’s really interesting as well as being so sad.

I visited the monument to the horses sent to war in Moji in 2015. A local man I met there said that 1 million were sent and none returned. I’ve attached the photos I took, in case you’re interested.

Thanks for the newsletters, they’re really interesting.

#000702 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

@Anna Foden: Hi Anna,

Thank you so much for your feedback and the photographs.

I have seen the 1 million figure for WWII several times. But I have been unable to confirm it, so went for the more conservative figures.

I love the monument in Moji. The water fountain makes it very personal. There is also a monument in Honbetsu, Hokkaido for WWII war horses. The History and Folklore Museum in Honbetsu also has a room with photos and objects related to this history.

It is described in the link that I shared in the notes. Here is the link to the pdf file again.

#000703 ·