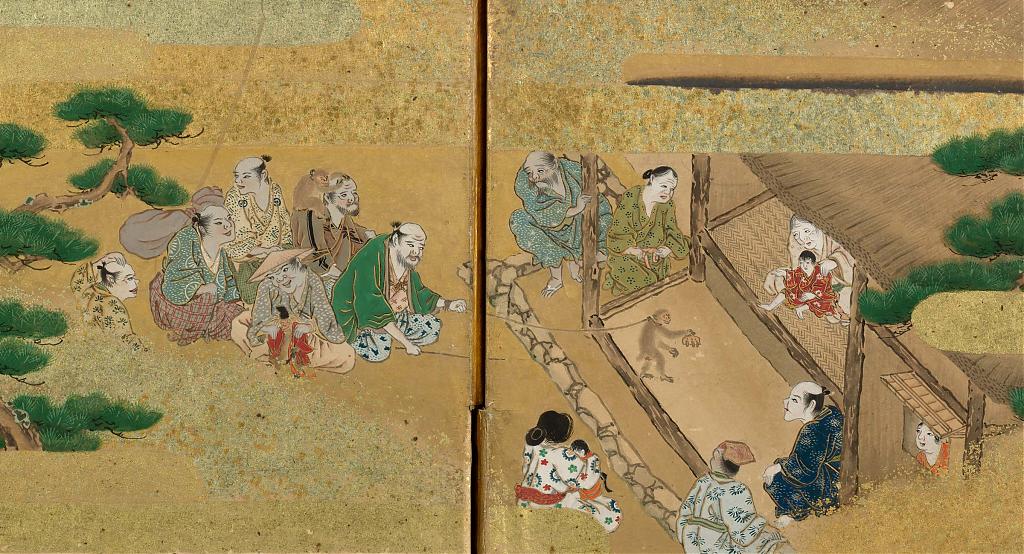

Children observe a traveling monkey trainer and his highly trained Japanese macaque monkey during a sarumawashi (猿回し) performance on the street. The trained monkey would perform to the trainer’s singing, the shamisen, or the beat of a drum.

Sarumawashi, probably introduced to Japan from the Asian continent, has a long and storied history that reaches back to the origins of Japan and enters the domain of gods and deities. In Japan’s founding myths, the monkey appears as a mediator and messenger between deities and humans.1

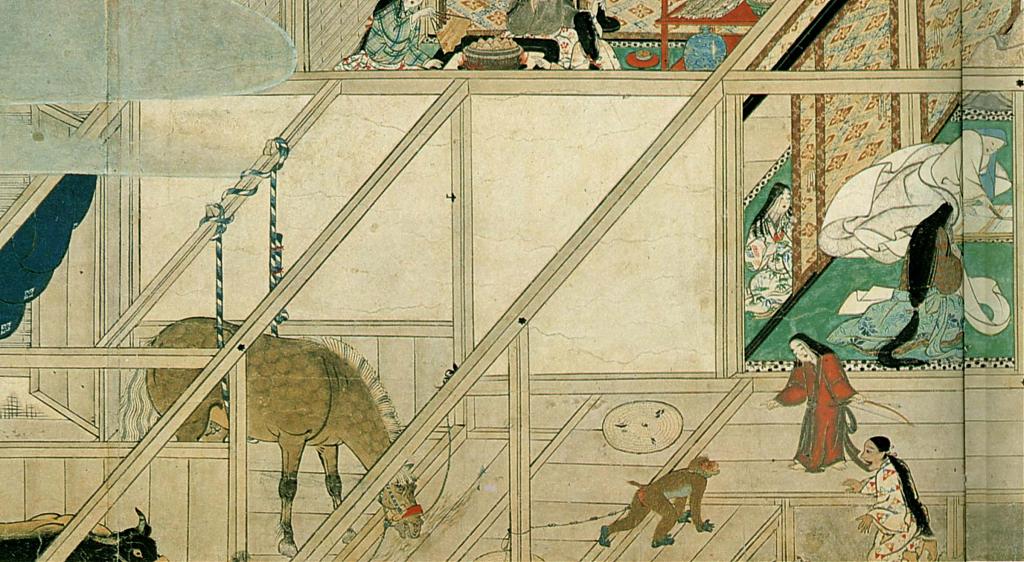

Its most important role was as the guardian of horses, with the power to heal sickness. Monkeys were even kept in stables to protect the horses. Samurai also covered their quivers with monkey hides for this purpose, while ema votive plagues depicting monkeys pulling horses were offered at shrines to pray for the health of horses.2

The origin of monkey performances was a ritual, performed at stables, to heal sick horses or improve their general welfare. This ritual was eventually extended to oxen as well. Later, it moved beyond stables and animals to the streets and individual homes.

In our modern world, entertainment and religion mostly occupy separate spheres. But in ancient Japan, performative arts were “first and foremost religious in nature,” writes anthropologist Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney in The Monkey as Mirror: Symbolic Transformations in Japanese History and Ritual.

Diviner-priests cured illnesses through rituals that were simultaneously religious and a form of entertainment.3

Entertainment, literature, oral tradition, and healing were inseparable and all were imbued with religious meaning.

The earliest known record of a monkey with his trainer is in the Nenjū Gyōji Emaki (年中行事絵巻, Picture Scrolls of Annual Events). The monkey has a rope tied to its neck, is not clothed, and walks on all four legs. Although published in the mid-thirteenth century, the document displays annual events of the late Heian Period (794–1185).4

The first accounts of trained monkeys that dance appear in 1245 and 1254, suggesting that monkey performances had already been established as a folk performing art in the thirteenth century. Apparently, the dances at the horse stables and the street performances were so similar that they could be performed by the same monkey.

A passage in the Kokon Chomonjū (古今著聞集), a collection of myths, legends, folktales, and anecdotes published in 1254, describes such a performance. It mentions that the audience watched in amazement, and that the monkey collected payment. It also features a description of the monkey’s clothing, which included an ebōshi, a hat of black lacquer worn by court nobles that is still worn by sumo referees today. The hat became a trademark of monkey performances.

From the 17th century on, monkey rituals at horse stables increasingly declined. But they continued to be seen as important by both the imperial and shogunal courts. Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616), who designated the monkey deity as the guardian of peace5, insisted that monkey rituals were performed after some of his horses fell ill.

The adoption of the monkey performances at the Shogunal Court originated from a well-known incident in which Ieyasu summoned Takiguchi Chōtayū from Shimousa (Chiba) because three of his horses became ill. When the horse recovered, Ieyasu rewarded Chōtayū by providing him with a piece of land and a fixed income; in exchange, Chōtayū conducted the monkey performance at Ieyasu’s stable three times a year.

These rituals were also performed for the daimyō in Edo. Generally as part of New Year rituals. Ogawa Montayū, a leader of monkey trainers, had 689 clients and took three months to complete his New Year obligations.6 As late as 1870 (Meiji 3), the Imperial Court still conducted monkey performances as part of New Year rituals. But as Japan modernized, they eventually vanished.

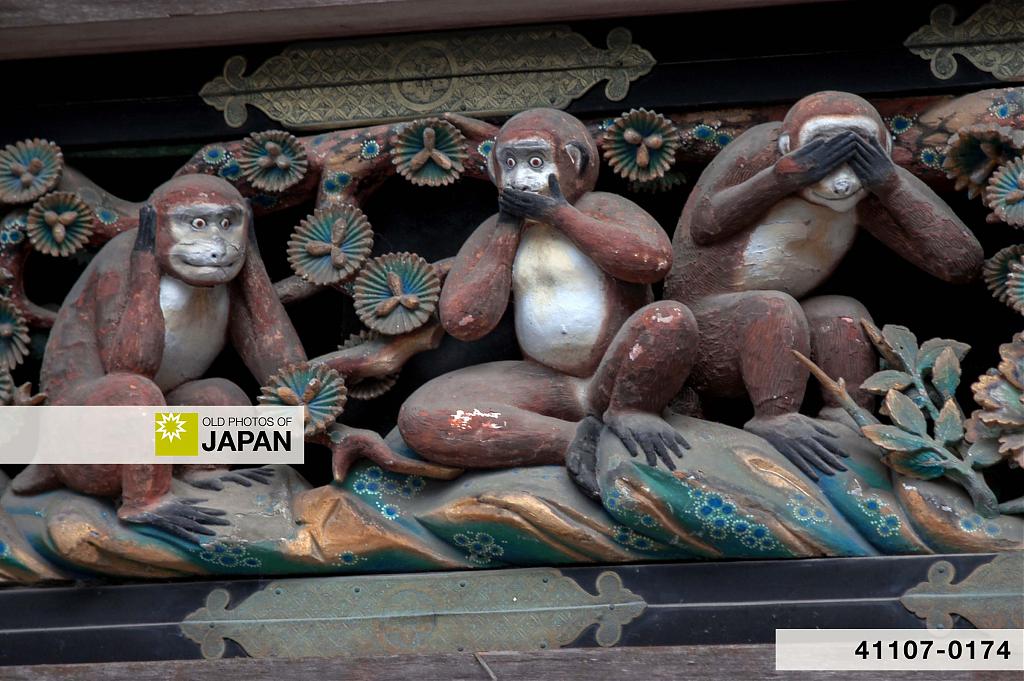

The custom may have long gone, but you can still see this ancient connection between monkeys and horses at the Nikko Toshogu Shrine. The famous woodcarving of the three wise monkeys can be found on the shrine’s sacred stable, one of eight carved scenes of monkeys adorning the building.

Although monkey rituals at horse stables were decreasing during the Edo Period, monkey performances as entertainment gained popularity. They were conducted on the street, on temple and shrine grounds (especially during festivals), in makeshift theaters, and at the doorways of individual homes. Here they generally took place on auspicious occasions like New Year, weddings, or the purchase of real estate. But in Edo and Osaka, they were also performed during funerals and annual commemorations for the deceased.7

Sarumawashi experienced its heyday during the late 19th and early 20th century. During this period, there were 150 trained monkeys and a similar number of trainers.8 In spite of their popularity, the performers were not always welcomed by the people. One trainer later recalled how some families chased him off and threw salt at the doorway to purify the area after his visit.9

This was because monkey trainers were generally burakumin, a group of people who were turned into an unofficial outcaste during the Edo Period and experienced extreme discrimination.

English traveller and writer Isabella Bird (1831-1904), who in 1878 travelled through the backcountry of Japan, even alluded to the low status of “monkey-players” in her book Unbeaten Tracks in Japan:10

Difficulties are often raised regarding the hire of rooms for Christian preaching. It is not “correct” for a missionary to preach in the open air. It places him on a level with “monkey-players,” jugglers, and other vagabond characters!

The discrimination and low esteem almost lead to the disappearance of this ancient tradition. When the burakumin liberation movement gathered speed in the 1920s, many members of the community tried to remove traces of their identity, including traditional occupations like sarumawashi. Over the following decades, the art virtually disappeared from the streets.

A group of young burakumin who believed that knowledge of their past was essential in asserting their identity, revived sarumawashi around 1977, 1978.11 They performed all over Japan, including very popular performances at Yoyogi Park in Tokyo during the 1980s. They also established theaters which became their home base.

The activities of this new generation were so successful that Sony used the monkey Choromatsu (1977–2007) in groundbreaking commercials for its Walkman portable audio players in 1987 (Showa 62).

Choromatsu was portrayed quietly listening to the music from his headphones in a beautiful and serene natural setting. He was composed as if in meditation, his eyes closed. The commercial left a strong impression on viewers at the time.

It is probably no exaggeration to say that even today, 35 years after it was first shown, anybody who saw the commercial when it first aired will be able to recollect both the commercial and how it made them feel. In a way, however briefly, this commercial brought the spiritual and commercial aspects of the Japanese monkey together.

In its modern form, sarumawashi’s religious meaning, with performances seen as a blessing from the deities, has been completely lost. Performances are now exclusively seen as entertainment. They resemble manzai, Japanese double act comedy. The focus is on clowning, with the monkey playing the role of the “funny man”, known as boke (ボケ) in Japanese.

Its highlight is the regular repertoire during which the trainer stages the monkey’s deliberate disobedience of an order, thereby implicitly challenging the human assumption of superiority over animals and, in addition, hierarchy in Japanese society in general.

During this comedy, the monkey performs al kinds of intricate actions, like jumping over blocks, walking on stilts, riding a bicycle, or jumping through a hoop. All of them emphasize the monkey’s bipedal posture, which must remind the viewer of humans.

Although it is intended to challenge the human assumption of superiority, it is unlikely that spectators get that message. They usually see the monkeys merely as cute, something that monkey trainers increasingly take advantage of by posting charming clips on YouTube.

Monkey Language

While sacred, sometime between the thirteenth and seventeenth century, the monkey also started to be portrayed as a malevolent trickster, and as a metaphor of undesirable human qualities.

Monkeys came to represent people who superficially imitated others, or who tried to reach beyond the status ascribed to them by society. Increasingly, undesirables and fools were referred to as monkeys.

This eventually crept into the language. Blind imitation is called sarumane (猿まね, “monkey imitation”), while sarujie (猿知恵, “monkey wisdom”) denotes shortsighted shallow cleverness. Japanese is full of such expressions.12

Interestingly, for many centuries these negative meanings of the monkey have managed to co-exist with the positive ones, and the belief that monkeys have sacred powers somehow survived. To the present day, charms and amulets with the likeness of a monkey are still used to ward of sickness and evil influences.

Notes

1 Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko (1987). The Monkey as Mirror: Symbolic Transformations in Japanese History and Ritual. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 41.

2 ibid, 49.

3 ibid, 80–81.

4 ibid, 104.

5 ibid, 44.

6 ibid, 115.

7 ibid, 115.

8 ibid, 119.

9 ibid, 121.

10 Bird, Isabella L. (1881). Unbeaten tracks in Japan: an account of travels on horseback in the interior, including visits to the aborigines of Yezo and the shrines of Nikkō and Isé. New York, G. P. Putnam’s sons, 204–205.

11 Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko (1987). The Monkey as Mirror: Symbolic Transformations in Japanese History and Ritual. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 123.

12 ibid, 58–66.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 1910s: Monkey Trainer, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on February 14, 2026 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/830/monkey-trainer

There are currently no comments on this article.