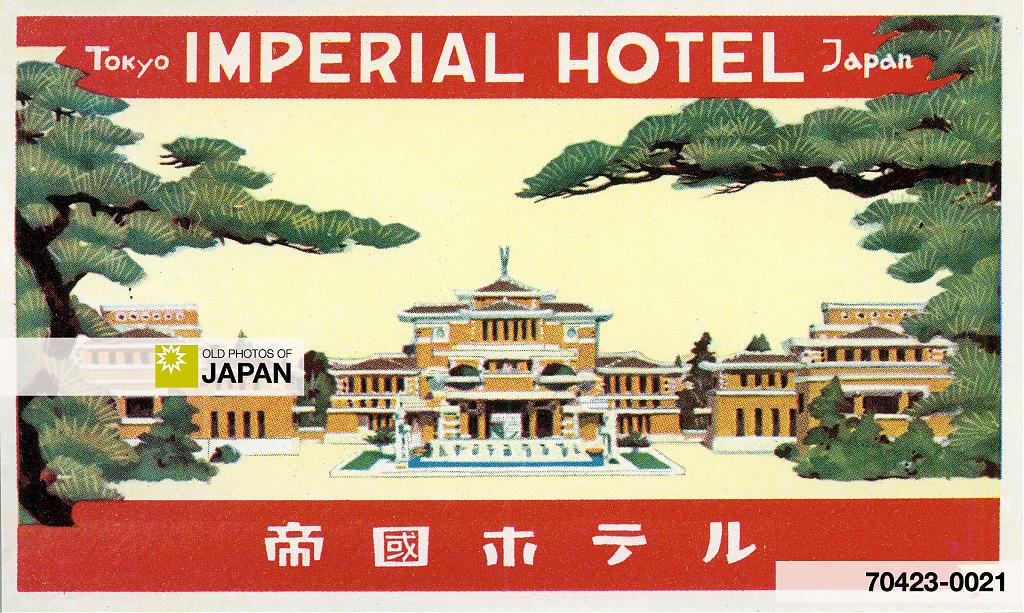

Today, few people in Tokyo will recognize this impressive Mayan Revival-style building with its wide courtyard and reflecting pool. But between 1923 (Taisho 12) and 1968 (Showa 43) it was Tokyo’s top luxury establishment, the Imperial Hotel (帝国ホテル, Teikoku Hotel) located in Hibiya.

The hotel was one of six buildings that legendary American architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959) built in Japan.1

Wright wanted to create a complex uneven surface to bring out light and shade and choose grey and green carved Oya stone from Tochigi Prefecture to accomplish this.

The architect had another, far more important, reason to use this stone. Wright was very aware of the danger that Japan’s earthquakes posed to heavy buildings and wanted to make the Imperial Hotel as earthquake-resistant as possible.

The plot covered a thick layer of mud and Wright decided he would make the Imperial “float upon the mud somewhat as a battleship floats on salt water.” His reasoning was simple: “Why fight the force of the quake on its own terms? Why not go with it and come back unharmed? Outwit the quake?”2 This required light building material. The light-weight lava stone from Oya was perfect for this.

Wright’s unconventional methods worried many though. Other architects considered the building’s foundations flawed and the American Institute of Architects predicted “that the whole thing would be down in the first quake with horrible loss of life.”3

When the Imperial Hotel opened on September 1, 1923 (Taisho 12), however, Wright was vindicated. That day it was hit by a magnitude 7.9 earthquake that devastated Tokyo, Yokohama, and the surrounding prefectures of Chiba, Kanagawa, and Shizuoka. Over half a million homes and buildings were destroyed, over 105,000 lives were lost.

Wright, who had left Japan in autumn of 1922, tensely waited for news about the fate of his building. “Appalling details came day after day. Nothing human, it seemed, could have withstood the cataclysm,” he wrote. “Ten days of uncertainty and conflicting reports, for during most of that time direct communication was cut off.”

But then he received a telegram from Baron Kihachiro Okura (大倉 喜八郎, 1837–1928), one of the principal investors4:

HOTEL STANDS UNDAMAGED AS MONUMENT OF YOUR GENIUS HUNDREDS OF HOMELESS PROVIDED BY PERFECTLY MAINTAINED SERVICE CONGRATULATIONS

Wright’s Imperial Hotel had survived. The reflecting pool that he had specifically built to provide a source of water for emergencies, and which had almost been cancelled because it was seen as a waste of money and space, had helped stop a raging fire. The hotel became instantly famous all over the world.

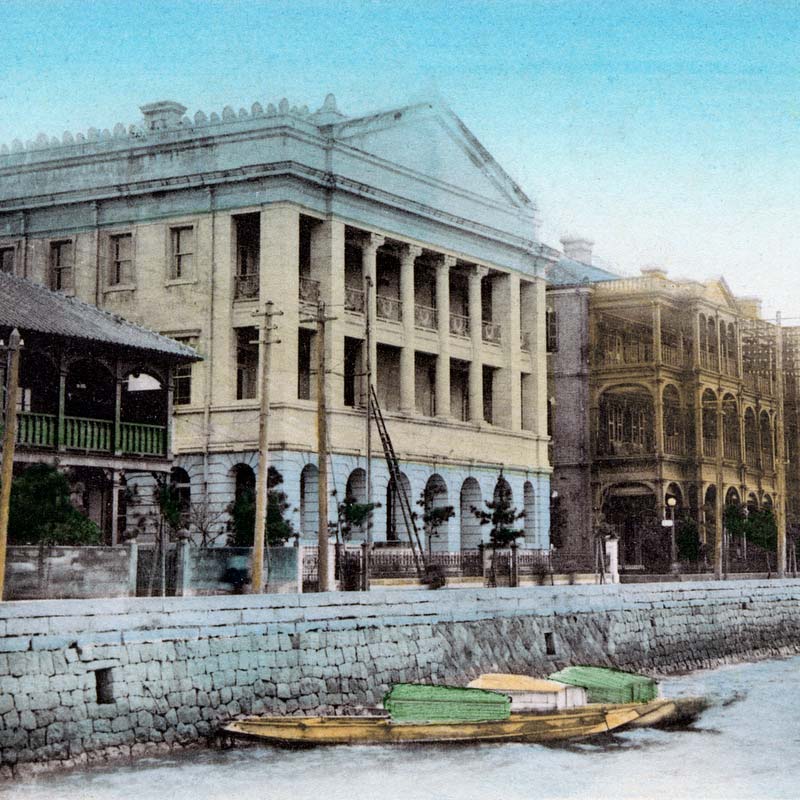

The event had an interesting side effect. It would change how Japanese got married. Wright’s Imperial was not the first building to carry that name. The first Imperial Hotel was opened on November 20, 1890 (Meiji 23) to cater to the increasing number of Western visitors. The hotel lost money at first and had to become innovative to survive.

When Crown Prince Yoshihito (1879–1926), the later Emperor Taisho, married on May 10, 1900 (Meiji 33), he did so in a Shinto ceremony at the Imperial Palace. This made Shinto weddings extremely popular, and the Imperial Hotel saw an opportunity. It set up a shrine-like altar and offered Shinto weddings followed by a reception.

Shinto priests, however were not amused. Many balked at performing a Shinto ceremony at a Western-style hotel. The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 destroyed their shrines though and the hotel was one of the few places where Shinto-style weddings could be performed. The number of weddings at the Imperial shot up, and the hotel ended up building its very own shrine on the premises, the very first hotel to do so.

This has become a regular feature at many large Japanese hotels, which now offer complete wedding packages featuring even makeup and hairstyling services, and photo studios for wedding pictures.

In 1967, the Imperial Hotel was demolished to make room for an ultra-modern high-rise structure. Wright’s main entranceway was preserved and moved to the Meiji-Mura museum near Nagoya. Here it still stands today, complete with the reflecting pond that Wright fought so hard for.

Notes

1 Frank Lloyd Wright designed some 14 buildings for Japan, of which six were built: the Imperial Hotel, its temporary Annex (1920), the Jiyu Gakuen School (Ikebukuro), the Aisaku Hayashi house (Tokyo), the Arinobu Fukuhara house (Hakone), and the Tazamon Yamamura house (Ashiya). Four structures remain: the Jiyu Gakuen Myonichikan, the Tazaemon Yamamura House, the front lobby of the Imperial Hotel, and a portion of the Aisaku Hayashi House. — Severns/Mori, Window on Wright’s Legacy in Japan. Retrieved on 2018-02-23.

2 Lloyd Wright, Olgivanna (1966). Frank Lloyd Wright: His Life, His Work, His Words. Horizon Press, 59. ISBN 0818000120

3 ibid, 69

4 Lloyd Wright, Frank (2005). Frank Lloyd Wright: An Autobiography. Pomegranate, 222. ISBN 0764932438

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Tokyo 1930s: Imperial Hotel, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on January 31, 2026 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/300/imperial-hotel-wright

Joe Kovacs

Hi Kjeld, I found Old Hotel Luggage Tags from the New Mori Hotel. in Tokyo, Japan. I’ve been Looking on the web & on e-bay looking for some info on the Hotel. my guess that’s it’s from the 1950’s???. on the back of tag is a small map & says conviently located to downtown near Shinagawa.

Thanks,Joe

#000636 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

@Joe Kovacs

Hi Joe,

I did some searching, but can’t find any info on the New Mori Hotel on internet… And I have never heard of it. Possibly, there are old phonebooks that list this hotel.

#000641 ·