Four Ainu fishermen stand in log boats, two of them holding spears as if ready to catch fish. Fish was, together with venison and other game, a very important part of the Ainu diet.

Fish was actually so important that in the many Ainu tales recalling famines, the cause is usually the absence of fish. The very Ainu word for fish, chep, is a contraction of chi-ep, which means food.1

“Coming from Japan,” one 19th century European observer wrote, “the first thing that strikes a traveller in the Ainu country is the odour of dried fish, which one can smell everywhere.”2 The primary catch was trout in summer, and salmon in autumn. Salmon was often called kamui chep, or divine fish. Other fish, like itou (イトウ, Japanese huchen) and ugui (ウグイ, Japanese dace), were also caught.

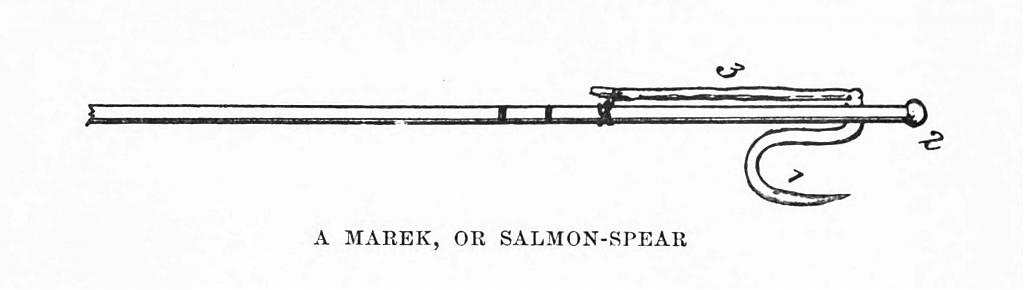

The most common spear used by the Ainu to catch fish was the marek (マレク).

The marek had a pivoting hook (1) fixed to a pole (2). After spearing the fish, Ainu fishermen would pull the string (3)—often made of sea-lion skin—to let the hook swivel down and prevent the fish from wriggling off.

Nets were also used. English painter, explorer, writer and anthropologist Arnold Henry Savage Landor (1865–1924), who visited the Ainu during an exploration in the late 19th century, gives a very vivid description of how the Ainu used them to catch salmon3:

We were not far from the river banks when shouts and cries of excitement reached my ears. I hurried on to the water-side and saw the two “dug-outs” swiftly coming down with the strong current, parallel with each other at a distance of about seven feet apart. There were three people in each “dug-out,” viz., a woman with a paddle steering at the prow; another woman crouched up at the stern, and a man in the middle. A coarse net made of young vines, and about five feet square, was fastened to two poles seven or eight feet long. The man who stood in the centre of each canoe held one of the poles, to the upper end of which the net was attached, and attentively watched the water. “They are catching salmon—look!” said Unacharo to me; “the salmon are coming up the stream from the sea.” The salmon net was plunged into the water between the two canoes, and nearly each time a large salmon was scooped out and flung into one or other of the “dug-outs,” where the woman sitting at the stern crushed its head with a large stone. If a fish escaped, yells of indignation, especially from the women folk, broke out from the boats, to be echoed by the high white cliff. Both men and women were naked, and the dexterity and speed with which they paddled their canoes down the stream, working the coarse net at the same time, seldom missing a fish, was simply marvelous. On the other hand, it must be remembered that fish were so plentiful in the river, that it was really easier to catch than to miss. In wading the Shikarubets (river) I could see large salmon passing me by the dozen, and I felt quite uncomfortable when some large fish either rubbed itself against or passed between my legs.

Besides the marek and nets, a 70cm (2 feet) long willow stick called isapa kik ni (イサパキクニ, head-striking wood) was used. It played an extraordinary role in Ainu culture. According to Ainu legend the salmon god got angry because salmon were killed with any tool that lay handy. The god told the Ainu to pay salmon the proper respect and use the isapa kik ni. Until they did, the salmon would not return. The starving Ainu agreed and the fish were bountiful once again.

A contemporary source describes how significant the isapa kik ni was4:

The Ainu say that the salmon do not like being killed with a stone or any wood other than good sound willow, but they are very fond of being killed with a willow stick. Indeed, they are said to hold the isapa-kik-ni in great esteem. If anything else is used the fish will go away in disgust.

Interestingly, in Landor’s description the woman used a stone to kill the fish.

The Ainu used several methods to prepare and store fish. Usually, the heads of the fish were removed, after which the fish were halved along the backbone and smoked. Salmon were also air-dried on trees, or from the rafters of the Ainu’s huts. Trout, which easily spoils, were grilled and dried. After preparation, the fish were stored in storehouses called pu (プ). Game, and wild as well as cultivated vegetables were kept here, too.

Salmon were not only used as food. The thick and tough skin of spawned salmon, for example, became material for making winter boots. Fish-oil in oyster shells was used for lighting.

With salmon playing such a major role in the daily life of Ainu, they understandably became a significant part of Ainu spiritual life as well.

The British Japanologist Basil Hall Chamberlain (1850–1935) documented many legends and stories told to him by Ainu. One of them is The Worship of the Salmon, the Divine Fish5:

A certain Aino went out in a boat to catch fish in the sea. While he was there, a great wind arose, so that he drifted about for six nights. Just as he was like to die, land came in sight. Being borne on to the beach by the waves, he quietly stepped ashore, where he found a pleasant rivulet. Having walked up the bank of this rivulet for some distance, he saw a populous place. Near the place were crowds of people, both men and women. Going on to it, and entering the house of the chief, he found an old man of very divine aspect. That old man said to him: ‘Stay with us a night, and we will send you home to your country to-morrow. Do you consent?’ So the Aino spent the night with the old chief. When next day came, the old chief spoke thus: ‘Some of my people, both men and women, are going to your country for purposes of trade. So, if you will be led by them, you will be able to go home. When they take you with them in the boat, you must lie down, and not look about you, but completely hide your head. If you do that, you may return. If you look, my people will be angry. Mind you do not look.’ Thus spoke the old chief. Well, there was a whole fleet of boats, inside of which crowds of people, both men and women, took passage. There were as many as five score boats, which all started off together. The Aino lay down inside one of them and hid his head, while the others made the boats go to the music of a pretty song. He liked this much. After awhile, they reached the land. When they had done so, the Aino, peeping a little, saw that there was a river, and that they were drawing water with dippers from the mouth of the river, and sipping it. They said to each other: ‘How good this water is!’ Half the fleet went up the river. But the boat in which the Aino was went on its voyage, and at last reached his native place, whereupon the sailors threw the Aino into the water. He thought he had been dreaming. Afterwards he came to himself. The boat and its sailors had disappeared—whither he could not tell. But he went to his house, and, falling asleep, dreamt a dream. He dreamt that the same old chief appeared to him and said: ‘I am no human being. I am the chief of the salmon, the divine fish. As you seemed in danger of dying in the waves, I drew you to me and saved your life. You thought you only stayed with me one night. But in truth that night was a whole year. When it was ended, I sent you back to your native place. So I shall be truly grateful if henceforth you will offer rice-beer to me, set up the divine symbols in my honour, and worship me with the words ‘I make a libation to the chief of the salmon, the divine fish.’ If you do not worship me, you will become a poor man. Remember this well!’ Such were the words which the divine old man spoke to him in his dream.—(Translated literally. Told by Ishanashte, 17th July, 1886.)

Unfortunately, the traditional Ainu subsistence economy, which was completely based on living off the land and barter, was disrupted when Japan’s economy underwent enormous growth during the Meiji Period (1868-1912).

Hokkaido possessed great natural resources and the Japanese government actively promoted the colonization of the northern islands. All over Hokkaido, mines, factories and fishing ports were constructed. Ancient forests were replaced by farms. Industrialized fishing fleets used huge nets to fish the seas surrounding Hokkaido.

New laws were enacted that restricted Ainu fishermen to specific days and locations and even the number of salmon they were allowed to catch. Hunting was outlawed and Ainu could not even cut a tree anymore without being arrested as criminals. Even the Ainu language was outlawed.

Many Ainu were often forcibly removed. Those that were not, starved because of the loss of their hunting and fishing grounds.

Not surprisingly, Ainu culture went into a desperate decline. It would take until the end of the 20th century, more than a century later, that a revival of Ainu culture was possible again. Finally, in 2006, the Japanese government implemented a project to recreate traditional Ainu living spaces (iwor) in Hokkaido.6 Young Ainu are once more learning their ancestor’s language, and many programs have been set up to create more awareness of the Ainu culture.

Once again, young Ainu are proud of their heritage, and there is hope for the future.

See all photos of Ainu.

Notes

1 Refsing, Kirsten (2002). Early European Writings on Ainu Culture: Religion and Folklore. Routledge, 519. ISBN 0700714863.

2 Landor, Arnold Henry Savage (2001). Alone with the Hairy Ainu or, 3,800 Miles on a Pack Saddle in Yezo and a Cruise to the Kurile Islands. Facsimile reprint of the 1893 edition by John Murray, London. Adamant Media Corporation, 5. ISBN 9781402172656.

3 Ibid, 64.

4 Refsing, Kirsten (2002). Early European Writings on Ainu Culture: Religion and Folklore. Routledge, 521-522. ISBN 0700714863.

5 Chamberlain, Basil Hall (1888). Aino Folk-Tales. Folk-Lore Society, xxxiv.

6 Ainu Assocoation of Hokkaido, Ainu Historical Events (Outline).

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 1900s: Ainu Fishermen, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on October 26, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/251/ainu-fishermen

There are currently no comments on this article.