How Bucket Brigades Consisting Mostly of Women Beat Modern Machinery

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4

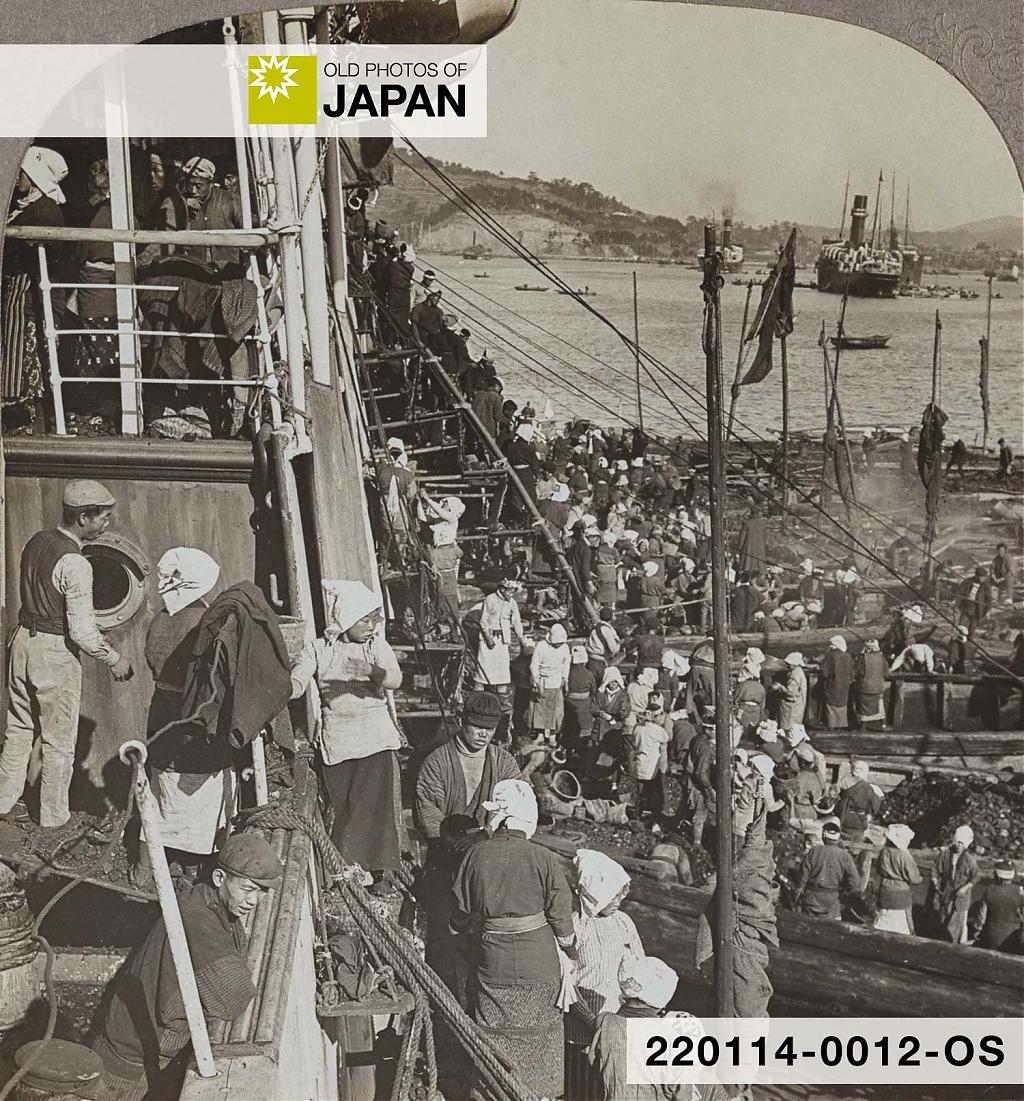

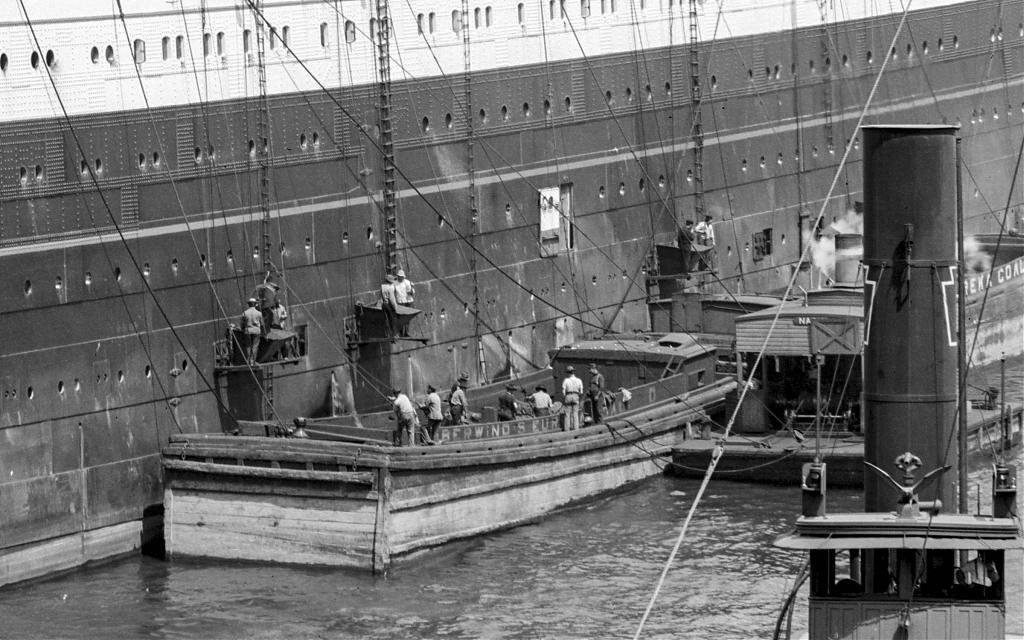

A “human conveyor belt” coaling a steamship in the harbor of Nagasaki. Even mechanized coaling stations could barely coal faster than Japanese crews. Women were crucial for this feat.

The remarkable Japanese way of coaling ships captured in this photograph and discussed in this four-part essay was known as tengutori.1 It was a direct result of the foreign pressure that Japan confronted during the 1800s.

The circumstances surrounding its creation help explain how Japan managed to avoid colonization when much of the non-Western world succumbed to it. It is a story of fortitude and innovation in the face of great adversity. As the saying goes, it is not what happens to one that matters, but how one reacts.

In this first article we look at tengutori through the eyes of the people that observed it, as well as how coal was stored on steamships.

The second article explores how tengutori came into being and why. In the third part we will look at the coaling ports as well as the people that did this incredible work, many of them indomitable women who considered themselves equal to men.

The fourth and final part delves into how the work was done from the viewpoint of the workers themselves.

The Japanese Way

By the 1870s, steamships started to become efficient enough to cross the Pacific. This greatly benefitted Nagasaki. Its sheltered natural harbor was close to large reserves of coal and located right on the edge of the Pacific. It was also relatively close to the important trading ports of Yokohama, Shanghai, Hong Kong and Singapore. As a result, it quickly developed into a crucial coaling station.

Steamships crossing the Pacific were hungry. In 1882 (Meiji 15), the 2,500-ton steamship Madras took on 671 tons of coal for fuel to travel from Seattle to Hong Kong.2 Engine efficiency was greatly increased over the following decades. But ships grew increasingly larger, requiring ever more coal. When the 18,000 ton Pacific Mail Steamer Korea bunkered in Nagasaki in 1908 (Meiji 41), it took in a massive 2,300 tons.

Hundreds of workers accomplished this feat in a mere six and a half hours—an average of nearly six tons per minute—without the help of any machinery.3 This rate of 350 tons an hour was only exceeded by fully mechanized facilities. But only just. Around the turn of the century, steam colliers using large baskets hoisted by steam power in the then very modern British port of Southhampton loaded at a rate of 400 tons an hour.4

Travellers were universally astonished. Even more so because in Nagasaki the majority of the loaders were young women. One traveller, the Episcopal bishop of New York, Henry Codman Potter considered it the most impressive thing that he experienced during his visit to Japan. He described the coaling of his ship in exquisite detail:5

If I were asked to say, of all that I saw in Japan, what that is that lives most vividly in my memory, I should probably shock my artistic reader by saying that it was the loading of a steamship at Nagasaki with coal. The huge vessel, the Empress of Japan, was one morning, soon after its arrival at Nagasaki, suddenly festooned—I can use no other word—from stem to stern on each side with a series of hanging platforms, the broadest nearest the base and diminishing as they rose, strung together by ropes, and ascending from the sampans, or huge boats in which the coal had been brought alongside the steamer, until the highest and narrowest platform was just below the particular port-hole through which it was received into the ship. There were, in each case, all along the sides of the ship, some four or five of these platforms, one above another, on each of which stood a young girl. On board the sampans men were busy filling a long line of baskets holding, I should think, each about two buckets of coal, and these were passed up from the sampans in a continuous and unbroken line until they reached their destination, each young girl, as she stood on her particular platform, passing, or rather almost throwing, these huge basketfuls of coal to the girl above her, and she again to her mate above her, and so on to the end. The rapidity, skill, and, above all, the rhythmic precision with which, for hours, this really tremendous task was performed was an achievement which might well fill an American athlete with envy and dismay. As I moved to and fro on the deck above them, watching this unique scene, I took out my watch to time these girls, and again and again I counted sixty-nine baskets—they never fell below sixty—passed on board in this way in a single minute. Think of it for a moment. The task I ought rather to call it an art, so neatly, simply, and gracefully was it done was this: the young girl stooped to her companion below her, seized from her uplifted hands a huge basket of coal, and then, shooting her lithe arms upward, tossed it laughingly to the girl above her in the ever-ascending chain. And all the while there was heard, as one passed along from one to another of these chains of living elevators, a clear, rhythmical sound, which I supposed at first to have been produced by some bystander striking the metal string of something like a mandolin, but which I discovered, after a little, was a series of notes produced by the lips of these young coal-heavers themselves—distinct, precise, melodious, and stimulating. And at this task these girls continued, uninterruptedly and blithely, from ten o’clock in the morning until four o’clock in the afternoon, putting on board in that time, I was told, more than one thousand tons of coal. I am quite free to say that I do not believe that there is another body of work-folk in the world who could have performed the same task in the same time and with the same ease.

Passing through Nagasaki in 1885 (Meiji 18), American author Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore (1856-1928)—the first woman to sit on the board of trustees of the National Geographic Society—was also fascinated by the hardworking young women:6

Many of the women were young and pretty, and some of them had brought their children, who, throwing back the empty baskets and helping to pass them along the line, thus began their lives of toil and earned a few pennies. The passengers threw to the grimy children all the small Japanese coins they possessed, and when the ship swung loose and started away their cheerful sayonaras long rang after us.

Loading coal for many hours on end was backbreaking and dirty work. An American commentator wrote in 1898 that it “causes more desertions from the navy than any other feature of the service.”7 Yet, during a visit to Nagasaki in the 1880s British major Henry Knollys (1840–1930) observed that the Japanese workers appeared to take the work in stride:8

The entire operation is accompanied with never-ceasing merriment and cracking of childish jokes. A piece of coal is too big for the baskets — it is tossed up bodily amidst screams of laughter. A girl topples over into the sea — the jest transcends all others. She swims like a cork on the surface of the warm, clear, blue water, and is dragged out, a veritable dripping little Venus, with her single strip of cotton clothing clinging closely to her small body.

American war correspondent George Kennan (1845–1924), who visited Nagasaki during the early months of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) made similar observations about the strength of the young women. He was especially impressed by how clean they managed to keep themselves. Notice that in Kennan’s description two women share the weight of a single basket, this differs from the accounts of others and the scenes seen in photographs.9

The work, of course, is hard, but as every basket is passed up by two girls standing opposite of each other, the weight actually lifted by each is only seven pounds. The seven-pound weight, it is true, has to be lifted and tossed 43 times a minute; but the muscles of the girls’ arms and shoulders become so hardened and developed by constant practice that like the legs of the jinrikisha men, they seem to be incapable of fatigue. The girls who coaled our steamer were apparently fresh when they finished their work, about 3 o’clock in the afternoon, and they all went ashore in the fleet of sampans, laughing and chattering as if they had been having an enjoyable lark. I was surprised to notice that they succeeded in keeping themselves fairly clean. The passing of coal in flexible loosely plaited straw baskets is dirty work, and men who engage in it soon get to look like chimney sweeps. Not so the Japanese girls. Their dresses were made of dark blue cotton which did not seem to retain or show coal dust; the white kerchiefs or towels in which they wrapped up their hair were protected by circles of coarse woven straw, bent down over their ears so as to make a sort of A-shaped thatch, and every girl carried somewhere in a pocket, a piece of cotton cloth, with which, when necessary, she carefully wiped away perspiration in such a manner as not to besmirch her face. Their hands and bare forearms, of course, were blackened; but even after four or five hours of basket tossing their faces, as a rule, were clean.

This site is funded by readers like you

Old Photos of Japan provides thoroughly researched essays and rare images of daily life in old Japan free of charge and advertising. Most images have been acquired, scanned, and conserved to protect them for future generations.

I rely on readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support this work.

Bunkering

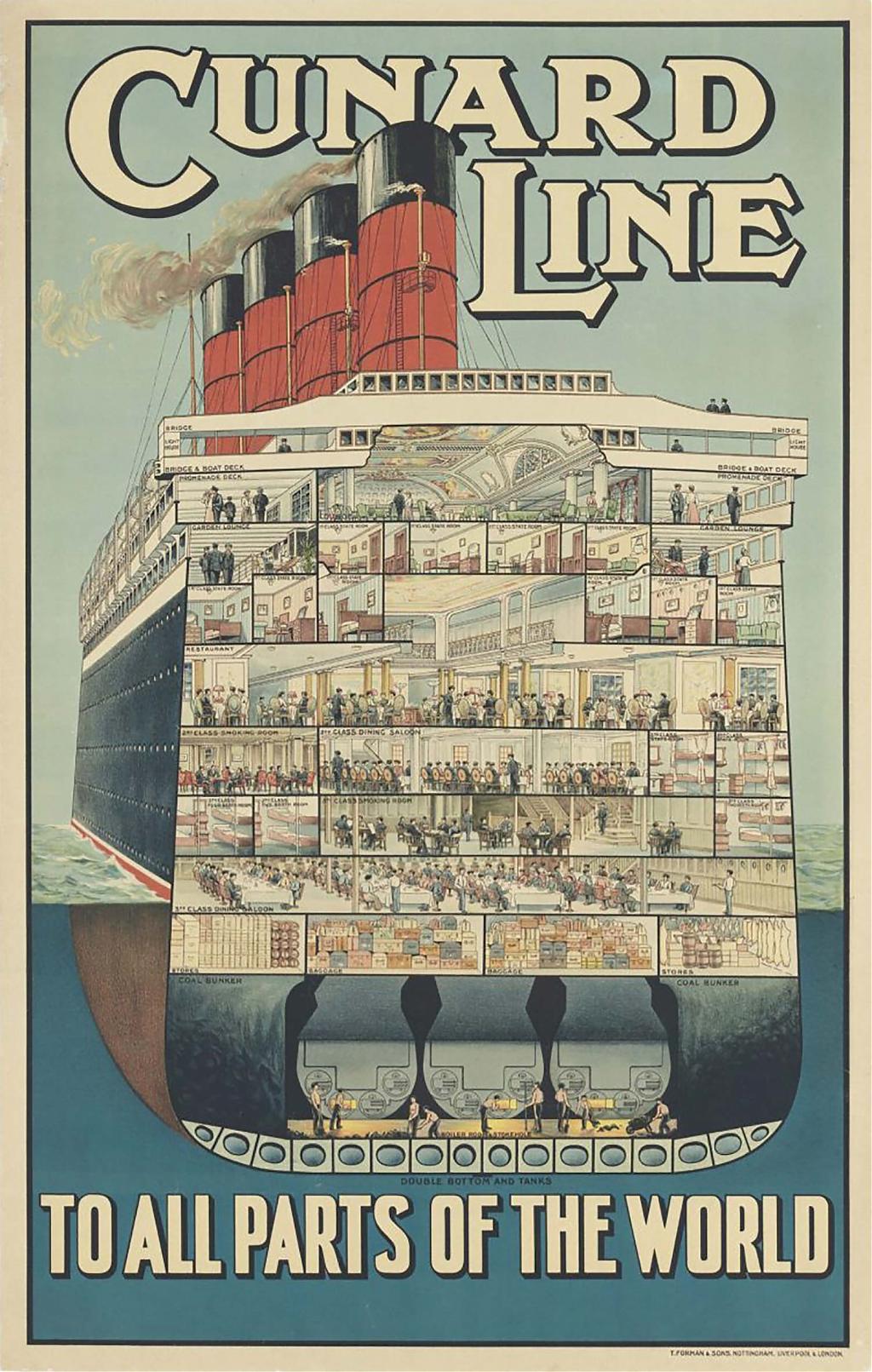

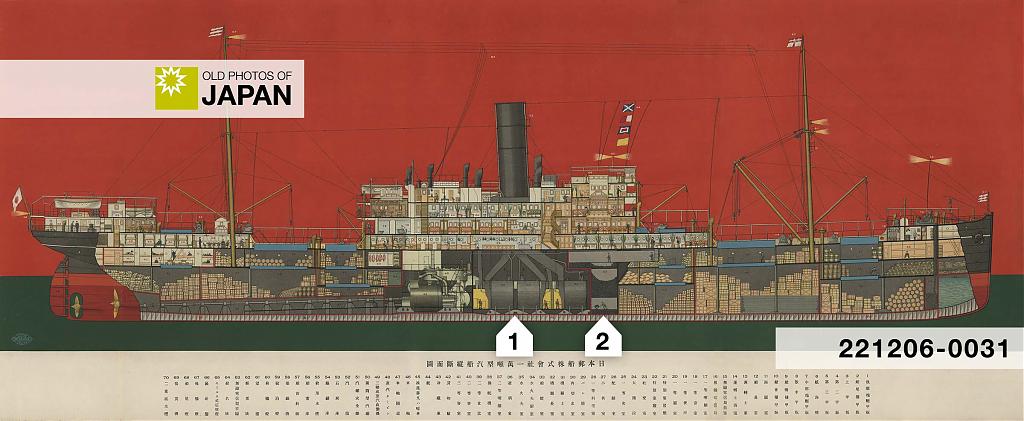

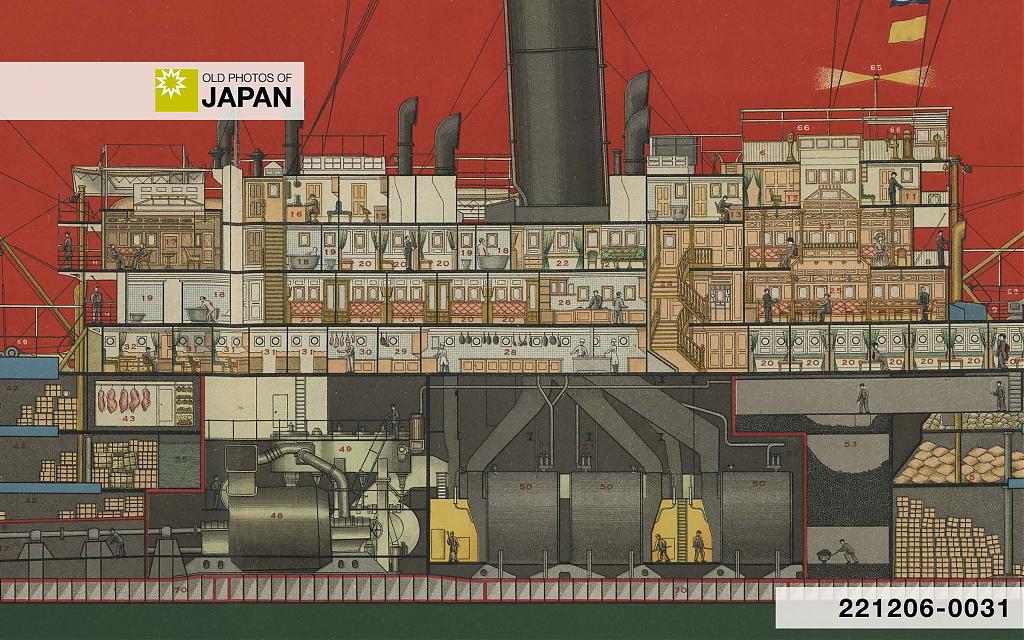

Loading a steamship with coal was a complicated procedure. Because the fine coal dust got into everything, coaling was a messy business. The job started with meticulously covering ventilators with canvas, and sealing off passenger areas.

On most ships the coal was ingested through ports in the hull, many of them close to the waterline. The coal ports fed into chutes connected to the coal bunkers, generally located at the lowest levels of the ship. Because the coal ports were often close to the waterline, they had to be carefully sealed and bolted after coaling was completed. Usually only one person on the ship was qualified and allowed to do do this critical work.

In many Westen ports a temporary platform was installed below each of the coal ports before coaling started. Two men stood on these platforms to guide buckets of coal from barges placed next to the ship using pulley systems rigged to the ship’s hull.

Trimmers inside the ship—overseen by the ship’s engineer—used shovels and wheelbarrows to spread the coal evenly over the bunkers. This job was just as critical to the safety of the ship as sealing and bolting the coal ports. If the leveling was not done right, the ship could list to one side and roll over during the journey.

As you can imagine, coaling was a time-consuming job. At many ports, coal bunkering could take between 24 and 48 hours. This is why the Japanese way of coaling attracted so much attention. It was completely different from how it was done at ports in other parts of the world, unbelievably efficient and fast.

Continue to Part 2 : How the tengutori method came into being and why.

About the English Accounts

There are surprisingly many accounts of coaling in Nagasaki in English language publications. The oldest mention I found was from June 24, 1876 (Meiji 9) in the British weekly illustrated newspaper The Graphic:

… boys and girls working for twenty hours on end in the heat of a Nagasaki midsummer, amid smothering coal dust, filling the bunkers of the mail-steamer.

The oldest descriptions were by Henry Knollys in Sketches of life in Japan published in 1887 (Meiji 20), a newspaper account in the Dubuque Daily Herald of November 20, 1887, and an article in the September 1, 1888 issue of The Graphic.

These last three match the date of the oldest photo of coaling in my collection. That was photographed in Nagasaki sometime between 1882 (Meiji 15) and 1892 (Meiji 25). The oldest coaling photo that I found was from 1872 (Meiji 5), although you cannot see people at work, just coaling vessels moored next to a ship.

From 1888 on, accounts appeared quite regularly until about the 1910s. Many make specific mention in their headline of women (or “girls”) doing the work.

An interesting short notice in the Spokane Daily Chronicle of October 28, 1932 (Showa 7) mentioned that the U.S. army transport coaling station in Nagasaki had been ordered closed. It noted the “human chain of Japanese women and children who passed hand to hand baskets of coal from barges to the ship.” The notice concluded with “Oil has replaced coal.”

Notes

1 The term “tengutori” originated in the Amakusa and Kumamoto regions, east and south of Nagasaki. It referred to passing things from hand to hand (e.g. in a bucket brigade). The term was also used for people passing roof tiles from hand to hand while standing on ladders. Tengutori (天狗取り) is believed to be a corruption of teguritori (手繰り取り, collecting, reeling in). 平原直(2000年). 物流史談 : 物流の歴史に学ぶ人間の知恵. 東京:流通研究社, 100.

The Japanese way of coaling ships was also referred to as the “human conveyer belt” (人間ベルトコンべヤ, ningen beruto konbeya).

2 Lange, Greg, First steamship to cross Pacific Ocean from Seattle departs in December 1882. Retrieved on 2022-09-13.

3 Schwartz, Henry B. (1908). In Togo’s Country, Some Studies in Satsuma and Other Little Known Parts of Japan. Cincinnati: Jennings and Graham/New York: Eaton and Mains, 200-201.

“Coaling a ship at Nagasaki is an interesting process. Before a ship has settled to her anchor, the large coal barges bear down upon her. In an incredibly short time a scaffolding of poles is tied in place from the ship’s side to the water’s edge, and upon each round of the improvised ladder a young girl takes her place, making a line of girls from the barge to the dock, up which living ladder the coal passes to the ship’s bunkers. Men in the barges shovel it up in shallow baskets holding a little less than half a bushel. This basket passes from hand to hand until it reaches the ladder, when the first girl seizes it and swings it straight up in front of her above her head, where it is caught by the girl above her; and so it goes on, from girl to girl, never stopping for a single minute until it finds its place in the bunkers of the ship. A line of small boys passes the empty baskets back to the barge to be refilled. Thus hour after hour the work goes on. You take out your watch to time them, and find the rate kept up with the regularity of machinery. Eighteen to the minute, twenty to the minute; laughing, talking the while, still the work goes on. Barge after barge is emptied and replaced by a full one, and yet the living elevator carries up the never-ending line of baskets until the last bunker is full, and then the ladders come down even quicker than they went up and the vessel is once more ready for her voyage to Hongkong or San Francisco and back.

“As an example of what can be done, the Pacific Mail Steamer Korea recently came into the harbor at half past six in the morning. Coaling started at eight, and continued until half past two in the afternoon. In the space of six and a half hours 2,300 tons of coal had been taken into the ship’s bunkers, an average of 353 3/4 tons per hour, nearly six tons per minute!”

「長崎港における石炭船積み作業は、おもしろいやりかたで行われる。船が錨をおろすかおろさないうちに、石炭を積んだ大きな艀(はしけ)がやってくる。信じられないほど短い時間の間に、丸太を組んだ足場が、艀と本船の間にでき上って、この即席の梯子の階段に、大勢の若い娘が位置を占めて、彼女らの手で、艀から本船の石炭庫へと、石炭籠が手送りされて、石炭が運び込まれるのである。艀の中の男たちは、半ブッシェル(一七・二リットル)を少し欠けるくらいしか入らない、浅いに、石炭をシャベルで入れる。籠は梯子まで手送りされて、最初の娘がそれをつかんで、上段の者に渡し、休みなく順繰りに送られて、船倉の石炭庫に運ばれる。小さな少年たちの列が、空(から)になった籠を、艀になげおろす。時計をとり出して、それを計ってみると、機械のような正確さで仕事が進んでいるのが分かる。一分間に一八回から二〇回の速度で、仕事は続けられていく。

艀が空になると、また石炭を満載した艀ととって代る。この人間エレベーターは休むことなく、籠を送り続け、石炭庫が全部一杯になると、本船は香港か桑港へ、船旅をつづける準備が整うのである。

一例を示すと、太平洋郵船のコレア丸が、朝六時半に入港し、八時に石炭積込みが始まり、午後二時半に作業は終了した。六時間半の間に二三〇〇tの石炭が積込みを終わったのだから、一時間に三五三t三/四、すなわち一分間に約六の速さである」。

An account in the January 1917 issue of The Journal of Geography claimed an even higher rate per hour in Nagasaki: “In this manner one of the largest ships on the Pacific recently loaded about 3500 tons of coal in six hours.” This comes to 583 tons per hour, or 9.7 per minute.

4 Office of Naval Intelligence (1900). Coaling, Docking, and Repairing Facilities of the Ports of the World: With Analyses of Different Kinds of Coal, Fourth Edition. Washington: Government Printing Office, 109.

5 Potter, Henry Codman (1902). The East of to-day and to-morrow. New York: The Century Co., 80–82.

6 Scidmore, Eliza Ruhamah (1891). Jinrikisha days in Japan. New York: Harper & brothers, 368.

7 Coal in Naval Warfare—Its Importance on Board Ship. American Machinist, Volume 21, McGraw-Hill, 1898, 33. Retrieved on 2023-10-21.

8 Knollys, Henry (1887). Sketches of life in Japan. London, Chapman and Hall Limited, 15–16.

9 Kennan, George (1904). Clean Japanese Girls in Blue Gowns and White Kerchiefs Put 2,000 Tons of Coal on Board in Eight Hours. The Norwalk Hour. Jun 27, 1904, page 6. Retrieved on 2023-10-17.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Nagasaki 1910s: Human Conveyor Belt (1), OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/878/vintage-photography-of-coaling-ships-in-nagasaki-japan

There are currently no comments on this article.