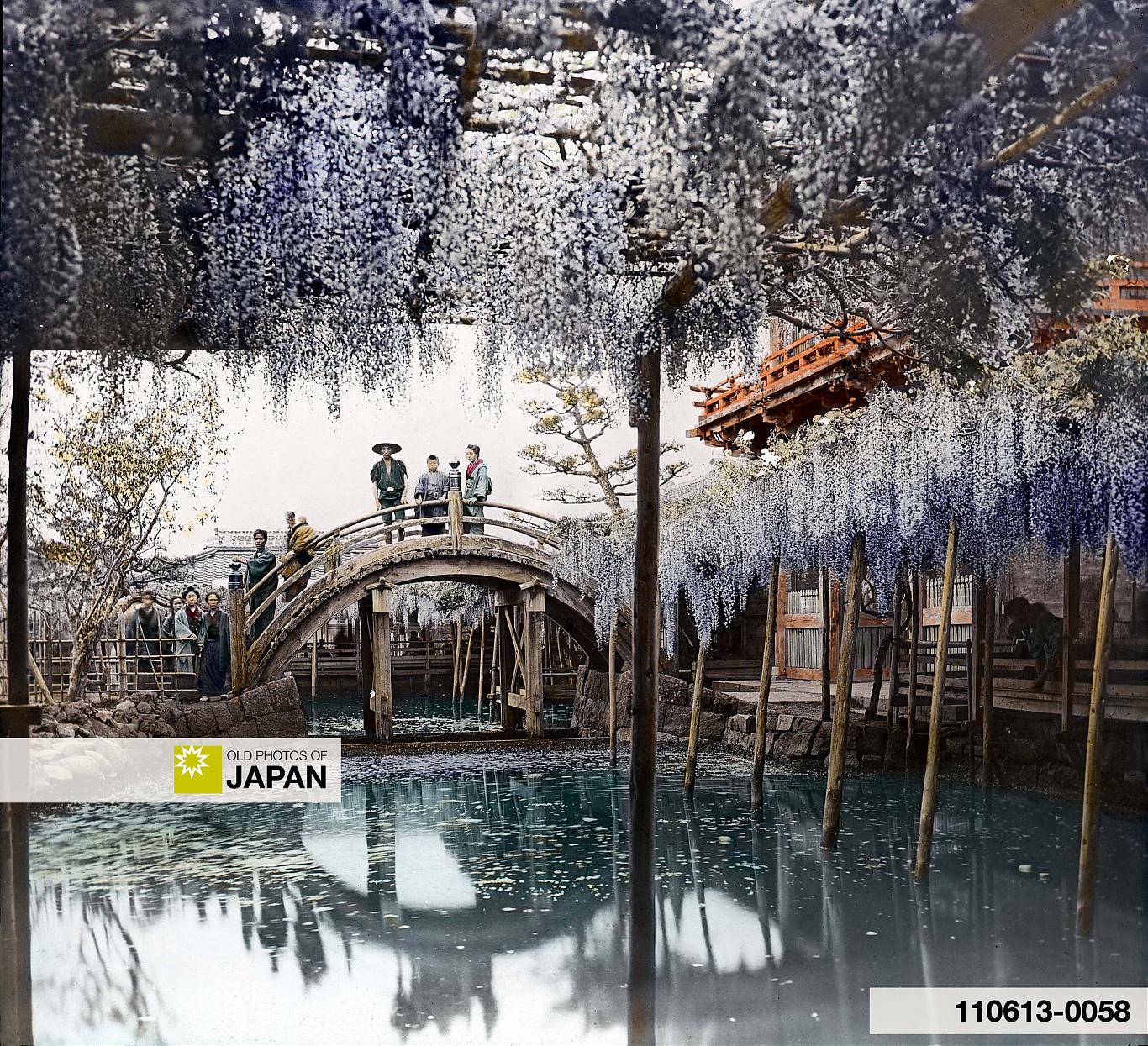

People are posing on the arched bridge at Kameido Tenjin, a celebrated shinto shrine in Tokyo. The pond is framed by an extended trellis with light purple wisteria.

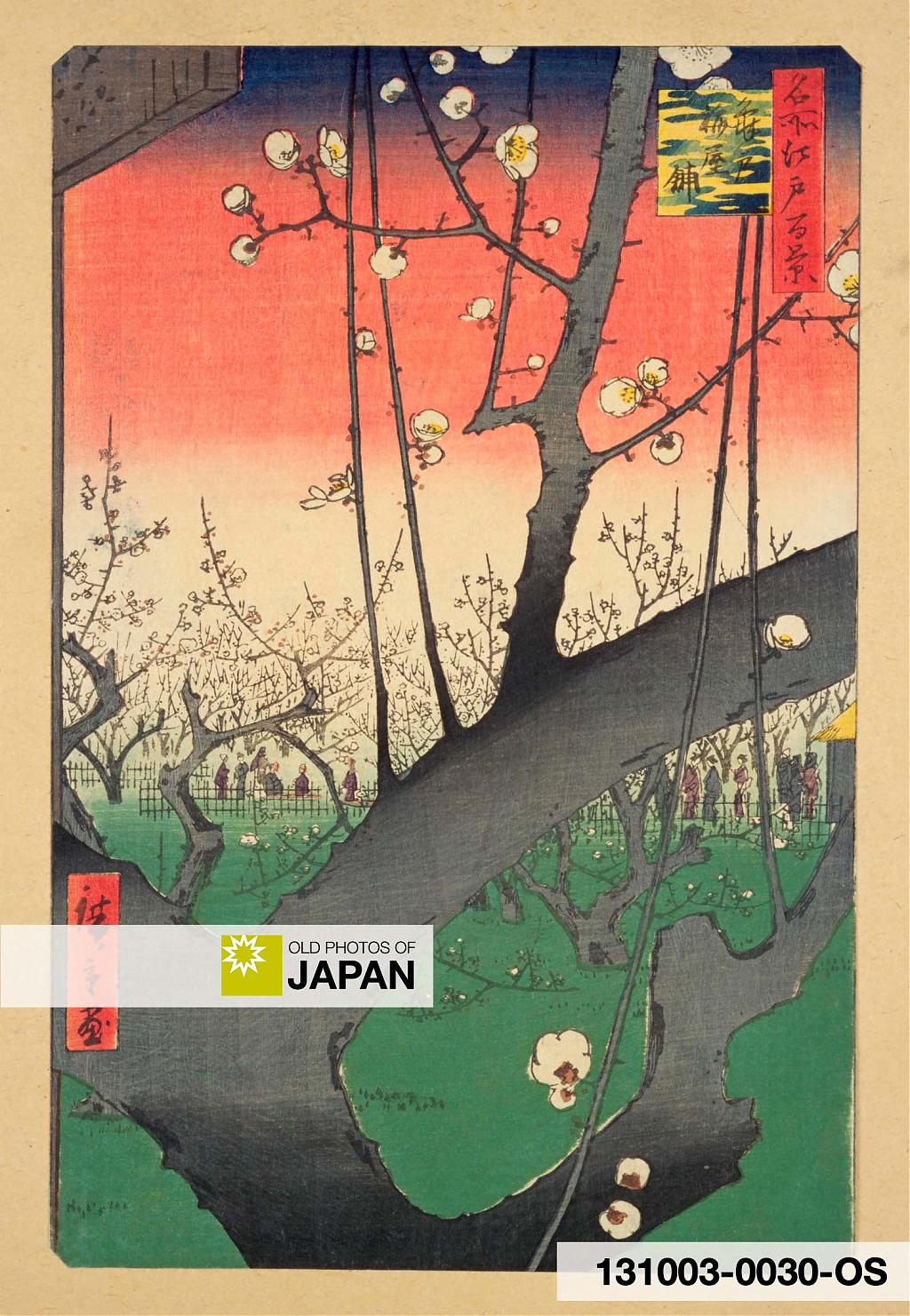

This photograph is a good example of how Japanese photographers in the 19th century gratefully borrowed from themes used in ukiyoe woodblock prints. A few decades earlier, in 1856 (Ansei 3), ukiyoe artist Utagawa Hiroshige (歌川広重, 1797–1858) had included this same scene in his series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (名所江戸百景, Meisho Edo Hyakkei).

Hiroshige was just one of dozens of Japanese artists that produced drawings and prints of the famous pond, arched bridges and blossoming trees of Kameido Tenjin.

Dedicated to poet scholar and statesman Sugawara no Michizane (菅原 道真, 845-903), today this Shinto shrine attracts a seemingly endless stream of students who pray here before their examinations.

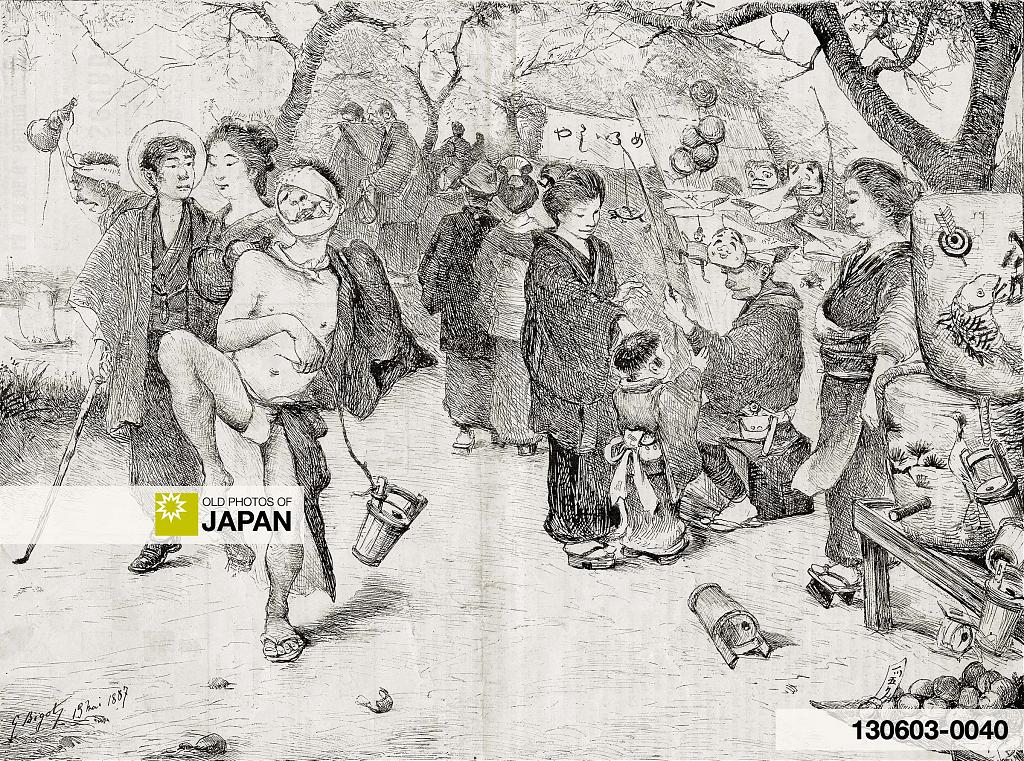

But over the ages, it has especially been popular for its dazzling displays of blooming wisteria. During the Edo Period (1603–1867), throngs of people would gather here every spring to admire the delicate flowers.

Hanami (flower viewing) is now mostly associated with cherry blossom, but in the past all kinds of blossoms brought the inhabitants of Edo (current Tokyo) out to party.

One reason was the severe travel restrictions of the Edo Period which tied people to the city. Commoners were generally only allowed to leave their town for pilgrimage. Although unbelievably popular, pilgrimage was not without danger. Travel could be a life-threatening adventure, writes Japanese author Jukichi Inouye (1862-1929) in his 1910 book Home life in Tokyo. This, believed the author, encouraged people to make better use of entertainment closer to home:1

The high roads were infested by robbers; and it was only with their lives in their hands that humble citizens could go on a long journey. Being, then, confined in the town, its inhabitants naturally took what pleasures they could in it and availed themselves of every festivity to give themselves up to enjoyment. The festivals of the tutelary deities were, for instance, celebrated with great pomp; on annual feast-days the time-honoured customs were religiously observed; and the flowers of the season were admired and made occasions for general hilarity, for they served to break the monotony of a purely urban life.

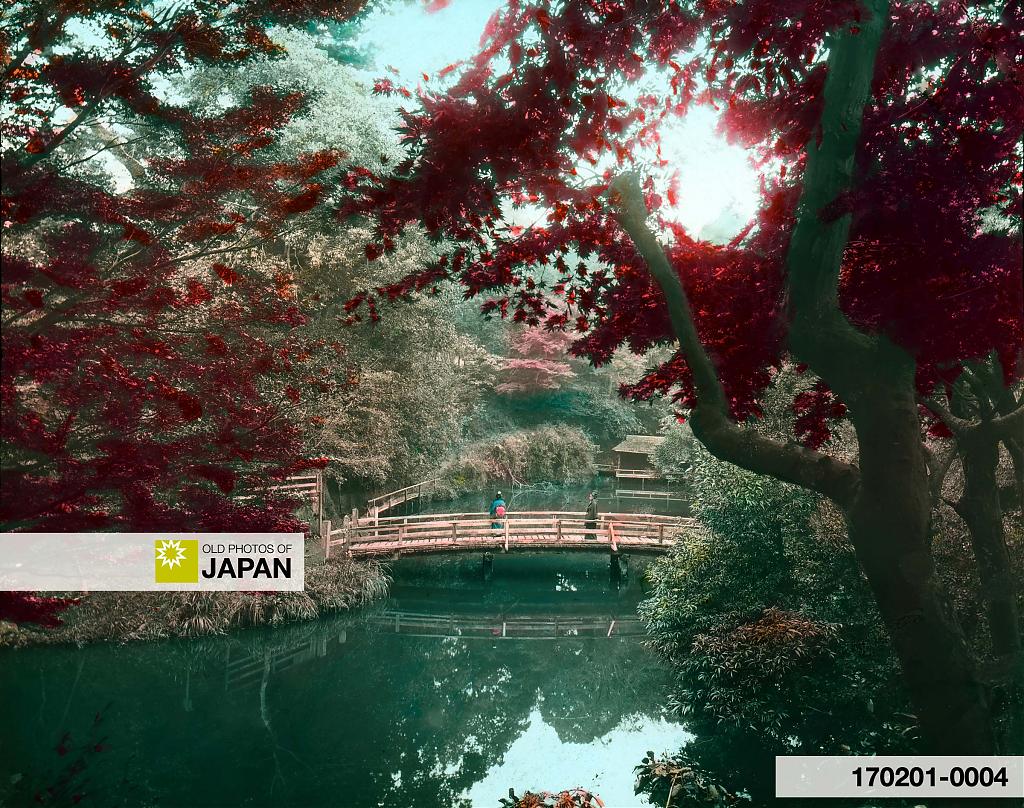

Each year, the flower seasons started with plum blossoms. Blooming in early March, they were seen as the harbingers of spring. As snow could occasionally fall while the plum trees were already in blossom, the image of a plum tree blooming under a layer of snow was used to represent faithfulness in adversity.

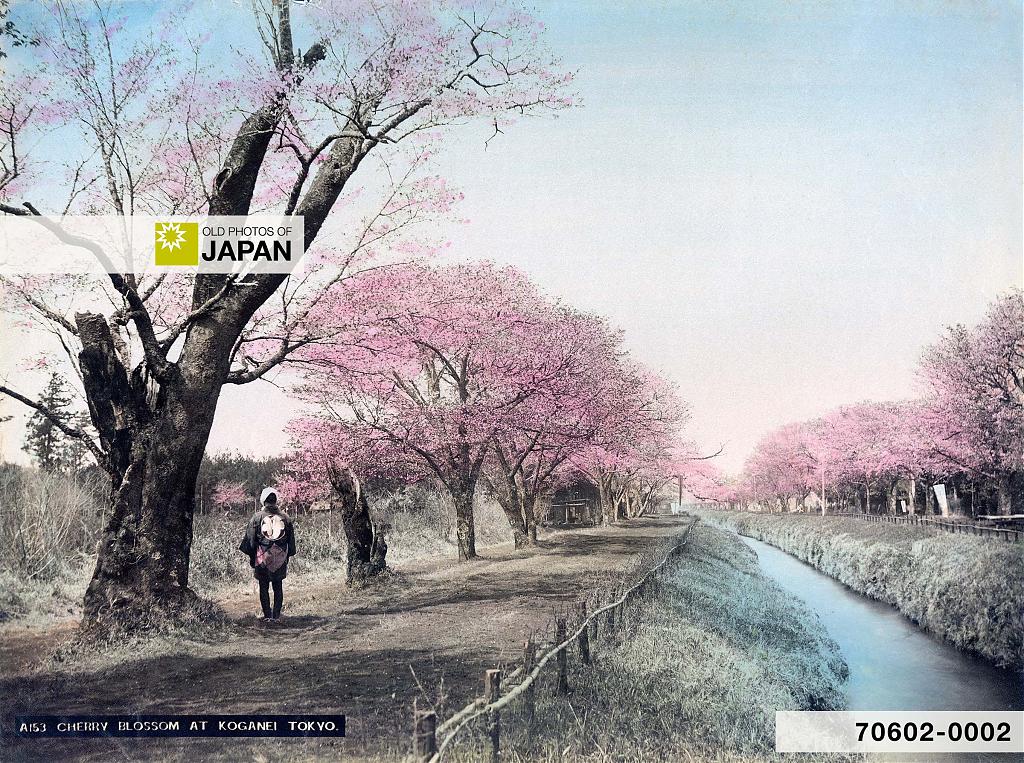

By late March, plum was followed by cherry blossom, the most popular viewing season of the year. It was at its height in the first half of April.

The earliest to attract crowds of pleasure-seekers is Uyeno Park, where along the walks and among other trees stand many aged cherry-trees. As the national museum and the zoological gardens are also in the park, the season attracts hosts of school-children who bring their luncheons and spend the whole day there. But it is the south-east bank of the River Sumida on the outskirts of the city, to which gather the largest throngs of sight-seers. Here an avenue of cherry-trees stretches for some miles, and men and women, as they pass under, are fairly intoxicated with the sight of the numberless clusters of cherry-blossoms. Many repair to it in parties, often in clothes of a uniform pattern and sometimes in comical guise. Next comes Asuka Hill, a few miles behind Uyeno, and then Koganei on a road west of the city, and lastly, the River Arakawa, on the north, noted for its cherry-blossoms of other colours than the usual pale pink. In the city there are many smaller spots where the blossoms may be seen to advantage.

Mukojima became a “fairy-land” during the cherry blossom season, wrote American author and geographer Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore (1856–1928) in 1910:2

… a mile-long tunnel of blossoms, where the branches meet overhead, and through which all the million inhabitants of Tokio (sic) seem to stream in unceasing procession day and night. No vehicles are permitted; policemen keep the crowds moving; double rows of tea-houses, booths, shops, and side-shows tempt the throngs; and house-boats and college crews make the river like another carnival. It is the festival of the common people, very often a rollicking saturnalia, for the miles of fairy flowers are matched by miles of sake tubs, and this mild rice-wine is a cheerful laughter-stirring drink, with no fighting qualities in its brew.

Later in April, the Tree Peony started blossoming. As this tree required special care, they were generally displayed in private gardens and nurseries, and rarely seen in public places.

Wisteria started blooming soon after the Tree Peony. Kameido Tenjin was the best place to view them. Here “their pendulous racemes look doubly beautiful as they are reflected in the pond over which they hang,” wrote Inouye.3

Another April flower was the azalea. One of the best places in Tokyo to view them was Ōkubo Village (around current Ōkubo Station). In 1899 (Meiji 32), Emperor Meiji even visited the area to admire the azaleas here.

In early June, large numbers of people admired the iris gardens in Horikiri and Kamata. The one in Horikiri (Horikiri Shobuen Garden) still exists, but sadly the Kamata Iris Garden closed down in 1921 (Taisho 10).

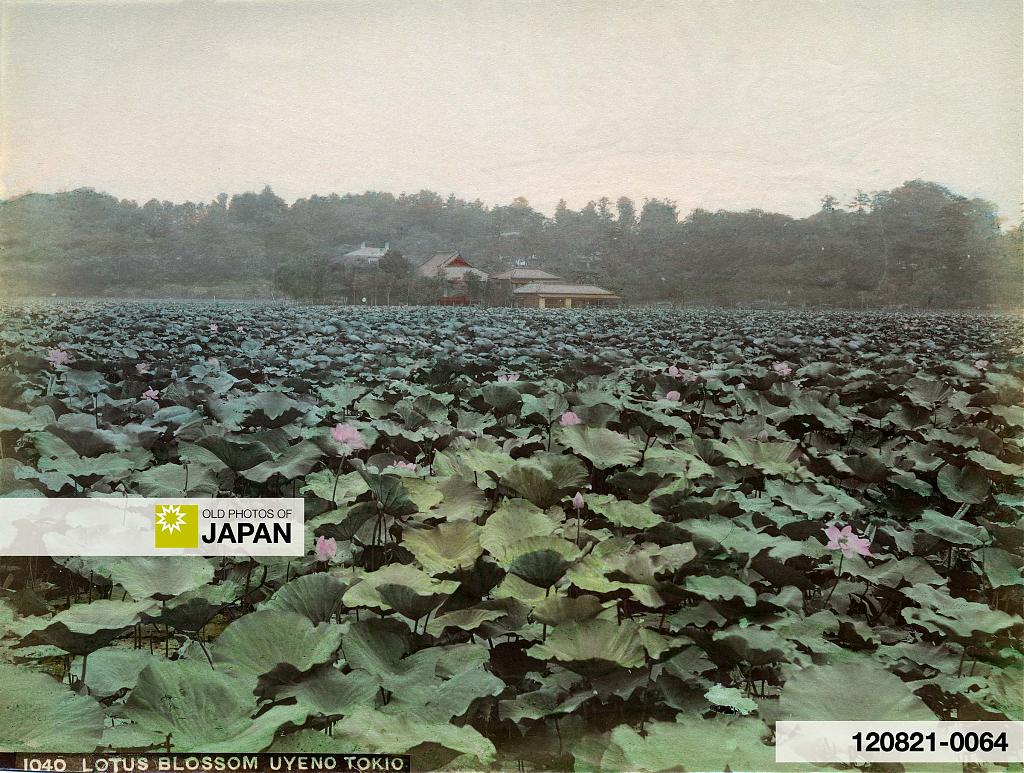

Iriya in the north of Tokyo was famous for morning-glory, which was in full bloom in August. On the way back, people would visit Shinobazu Pond at Ueno Park to admire the lotus there.

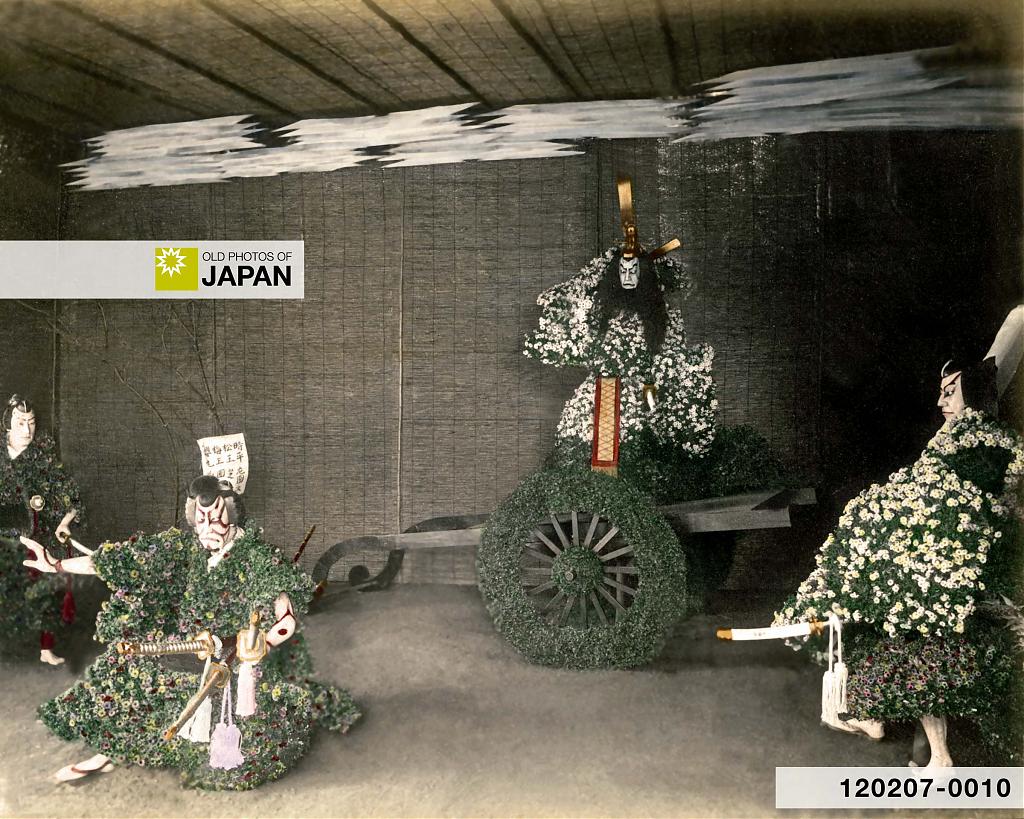

Together with cherry blossom, Japan’s most important flower was arguably the chrysanthemum, the symbol of the Imperial family. While cherry blossom represented spring, chrysanthemum represented autumn in Japan. It bloomed from September through November:4

In [November] the chrysanthemums are in full bloom; at Dangozaka, not far from Uyeno Park, are exhibited scenes from well-known plays or representations of passing events, in which the figures are clothed with chrysanthemum flowers of various colours. They attract large crowds; but the finest flowers are to be seen in the palace-grounds at Akasaka, where the Imperial chrysanthemum party is given, and at the mansions of noblemen and men of wealth. This month is also noted for the maple-leaves, which, when they become crimson, are highly admired; and many people make pilgrimages to the banks of the Takinogawa, a few miles north of Uyeno Park, where they are to be seen in great profusion.

Very few of these places managed to survive beyond the Meiji Period. Modern public transportation allowed people to escape the city. They still went out to admire seasonal flowers, but increasingly did so far from Tokyo.

In her 1910 article in The Century Illustrated Monthly, Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore already mentions “many special cherry-blossom excursion trains” that took people far away from their homes.5

More than a century later, the inhabitants of Tokyo have not lost their love of flowers. The Imperial Household Agency even has a flower calendar on its website to show which flowers can be found on the Imperial Palace grounds, and when they bloom.

Edo–Meiji Flower Calendar for Tokyo

Flowers, their seasons, and some of the most popular areas in Tokyo where people enjoyed hanami during the Edo and Meiji periods.6

Spring (March ~ May)

| Plum • Ume (梅) | Early March

|

|---|---|

| Peach • Momo (桃) | Early March ~ early April Peach attracted few viewers, writes Inouye. Possibly because it was overshadowed by plum and cherry blossom. |

| Cherry Blossom • Sakura (桜) | Late March ~ early April

|

| Tree Peony • Botan (牡丹) | Late April Viewed at private gardens and nurseries. One was Yoshinoen (吉野園) at Yotsume (四つ目) in Honjo (本所, current Sumida-ku). |

| Wisteria • Fuji (藤) | Mid-April ~ May

|

| Azalea • Tsutsuji (つつじ) | April ~ May

|

This site is funded by readers like you

Old Photos of Japan provides thoroughly researched essays and rare images of daily life in old Japan free of charge and advertising. Most images have been acquired, scanned, and conserved to protect them for future generations.

I rely on readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support this work.

Summer (June ~ August)

| Iris • Hanashōbu (花菖蒲) | Early June

|

|---|---|

| Hydrangea • Ajisai (あじさい) | Early June ~ early July Although native to Japan, hydrangea got little attention until it had been improved in the West and was reimported. This started happening from the Taisho Period (1912–1926). Inouye mentions hydrangea only once in his book, and it rarely appears in ukiyoe. Its current popularity dates from after the end of WWII in 1945. |

| Morning Glory • Asagao (朝顔) | August

|

| Lotus • Hasu (蓮) | Mid-July ~ August

|

Autumn (September ~ November)

| Chrysanthemum • Kiku (菊) | September ~ November

|

|---|---|

| Seven Flowers of Autumn • Aki no Nakakusa (秋の七草) | September The seven flowers of autumn were Japanese clover (hagi), Japanese pampas grass (susuki), Japanese arrowroot (kuzu), large pink (nadeshiko), yellow flowered valerian (ominaeshi), thoroughwort (fujibakama), and Chinese bellflower (kikyō). Mukojima was one of the spots where people went to see these flowers. |

| Maple • Kaede (カエデ) | November

|

Winter (December ~ February)

| Camellia • Tsubaki (椿) | December ~ April Camellia attracted few viewers. Possibly it was too cold to party outside. |

|---|

Notes

1 Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home life in Tokyo by Inouye. Tokyo: The Tokyo Printing Company Ltd, 287.

2 Scidmore, Eliza Ruhamah (March 1910). The cherry-blossoms of Japan: Their season a period of festivity and poetry, The Century Illustrated Monthly, Volume LXXIX, No. 5: 653.

3 Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home life in Tokyo by Inouye. Tokyo: The Tokyo Printing Company Ltd, 297.

4 ibid, 304.

5 Scidmore, Eliza Ruhamah (March 1910). The cherry-blossoms of Japan: Their season a period of festivity and poetry, The Century Illustrated Monthly, Volume LXXIX, No. 5: 650.

6 The flowers and locations in the seasonal tables are referenced from old guidebooks, ukiyoe, vintage photographs and Home life in Tokyo by Jukichi Inouye (1910), pp. 287–305.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Tokyo 1890s: Wisteria at Kameido Tenjin, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on November 27, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/866/wisteria-at-kameido-tenjin

There are currently no comments on this article.