In July 1871 a strong typhoon devastated western Japan. It was one of the first strong typhoons that foreigners in the newly opened foreign settlements experienced and it shocked them tremendously.

In Osaka and Hyogo prefectures alone some 700 people were killed.1 Even the sturdy brick buildings in Kobe’s brand new foreign settlement could barely withstand the storm’s fury.

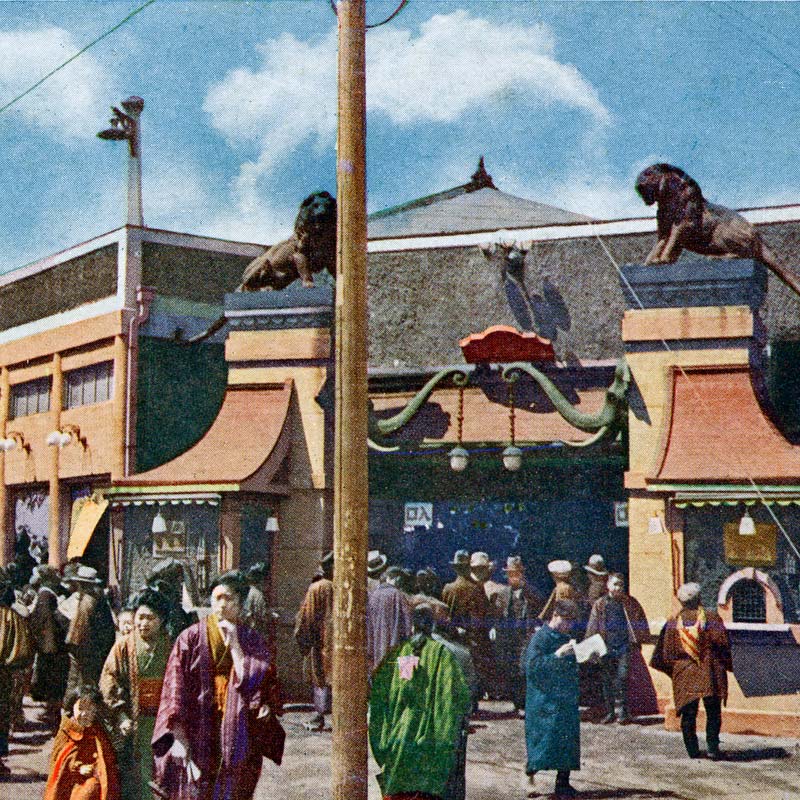

Japan had opened for international trade only twelve years earlier, in 1859 (Ansei 6). Kobe’s foreign settlement had been open for just three years and construction was still ongoing. The building in the foreground—the Hiogo Hotel—was actually one of these uncompleted buildings. It was located right at the waterfront.

Local newspaper the Hiogo News called the damage to the port “very serious.”2

Since the opening of this port to foreigners, storms of more or less violence have visited it, but their effects were as nothing compared to that which visited us on the night of Wednesday and the morning of Thursday last. It had been brewing all day, and between nine and ten o’clock, the wind was at its height, and it was evident that we were experiencing the effect of a severe typhoon. This alone would have done but little damage, but at about twelve o’clock the water in the harbour began to rise rapidly, breaking over the sea wall, and flooding the Settlement in some places to the depth of three feet [0.9 meters], some low-lying places in the Native Town being at least five feet [1.5 meters] under water. Fortunately the water receded as quickly as it rose, and by two o’clock it had entirely subsided. The damage done during the short time the waters had full play, however, was very serious.

The newspaper gave a detailed account of the extensive damage, which included the destruction of the British government’s “coal sheds.” Some 500 tons of coal and 2,000 cases of kerosine oil were washed away.

A “large iron safe” of “at least five tons” was found 9 meters from its original location. The important sea wall was almost completely washed away and at least ten steamships were washed ashore, several of them irretrievably wrecked.3

Amongst the foreign shipping the most serious loss is the British barque Pride of the Thames, which dragged her anchors, and after skirting the Bund wall for some time, came on shore close to the American Hatoba, and at one o’clock went on her beam ends. We have not yet ascertained how many of her crew were lost, but it is certain that the Captain, the first and second mate, and two others, have perished; but none of the bodies have yet been recovered. Those who were saved, escaped almost miraculously. One was drifting round the harbour for some time, till he was picked up by the Augusta. Three were rescued from the wreck, to which they were clinging, by Messrs. Sim, Blackwell and A. Stewart swimming off to them with a rope, which was attached to a boat, and another was picked off the wreck by a boat from the Augusta.

The Japanese inhabitants of Kobe and the neighboring town of Hyogo suffered most. Hundreds of lives were lost:4

Many native boats have been completely destroyed in Kobe harbour, accompanied, we fear, with much loss of life. At Hiogo [sic] the storm appears to have raged with even greater violence than at Kobe. Between two hundred and fifty and three hundred houses have been destroyed along the shore, and about six hundred boats are reported lost, the number of sound junks left in port being few indeed. Of course the loss of life has been immense. The Authorities have not yet ascertained the number of people who have perished during the storm, but the dead are estimated at something between 400 and 600, besides a considerable number of wounded. One junk which was wrecked had 200 persons on board, all but three of whom have perished.

Over the following years, Japan’s foreign residents became intimately acquainted with the power of typhoons. After a typhoon wrought destruction on Tokyo in 1880 (Meiji 13), a French resident wrote about the great fear he had felt:5

I never spend such a fearful night; it seemed as the coming of Doomsday. Tiles were flying about in every direction, the oldest trees bent like rushes before the terrible wind. Whole roofs were uplifted and blown to a great distance just like saucepan lids; at the Fine Arts School there is not a whole door or window left; three houses fell down not far from my residence.

In 1934 (Showa 9), the aftermath of the destructive Muroto typhoon was caught on film, probably the oldest footage we have of typhoon damage in Japan. At the time it was regarded as the “second-greatest catastrophe of modern Japan,” the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923 (Taisho 12) being the greatest.

Over 3,000 people were killed and some 200,000 people were left homeless. Especially Osaka was hit hard, accounting for over half of the deaths.

Typhoons at Sea

Typhoons were even more terrifying at sea. Especially in the 1800s when travel to Japan was by steamship or sail. Encountering a typhoon at sea could mean the end of the journey.

Many travelers who did make it through wrote about their experience in their diaries. German physician and botanist Philipp Franz von Siebold, an influential doctor of the Dutch trading post at Nagasaki’s Dejima, was one of them. This is Siebold’s diary entry for August 5, 1823 (Bunsei 6):6

Now the wind was howling terribly, the sea was running high, and as the waves were short, they caused a dangerous pounding and banging with a violent impact against the sides of the ship. Night fell, and with it the storm became even more violent. It was no longer possible to stand freely on the deck; voices were lost within a few steps, and the speaking tube gave unintelligible sounds. Only the white peaks distinguished the waves from the clouds. The ship’s boys and younger sailors had to leave the deck, the strongest and bravest stayed. Around 11 o’clock a hurricane, a typhoon as mentioned above, raged accompanied by torrential rain, which fell like hail on the crew and became unbearable. The sea beat incessantly on the deck; the boats, water barrels and whatever else was attached to them tore loose and the starboard bulwark was smashed to pieces. The ship often remained under water up to the large hatch for minutes at a time. There were moments when one doubted whether the bow, sunk into the sea, would rise again. The masts cracked terribly and the whole hull shook with them. The hatchets were brought in and they were ready to cut the masts at any moment, firmly convinced that with the masts standing the ship would not be able to withstand such a hurricane for long. To our utter amazement, there was no more than 16 inches of water in the pumps. Inside the ship, we had to fight the gale no less than our good helmsmen and sailors on the deck, where they defied the fury of two elements with admirable endurance. The situation was desperate no matter where one was. In the cabins every precaution had been taken to secure the equipment, but in vain. With the terrible rolling, rising and falling of the ship, everything was shaken loose; chairs, benches, tables, boxes and suitcases rolled around and nothing provided a firm foothold. We were all mired down in the cabin, deprived of fresh air, without light and exhausted by the constant tossing around. Each of us was looking for a firm foothold here and there, from which, together with a piece of equipment that had been torn loose, he unexpectedly rolled from one corner to the other onto his traveling companions.

Totally exhausted, and unwilling to die in the company of others, Siebold somehow managed to sleep. When he woke the storm had mostly gone and he went on deck. When he saw the crew he was shocked by how their faces had changed.

The hardships suffered by the crew during such accidents at sea cannot be described, and it is often incomprehensible how people can endure them. On some of the faces I knew so well, the prolonged exertion had brought about such a change — leaving behind such distorted features of despair and exhaustion that I hardly recognized them at first sight.

After steamships were invented things improved a bit. Ships could now steam out of the storm. However, the experience remained intimidating.

In the 1880s, British Army officer Henry Knollys (1840–1930) encountered a typhoon while traveling to Japan on a steamship. He was “awakened by a din resembling that which would be caused by several bulls in a china shop.”7

The crockery and glass are crashing, the furniture and boxes are flying about in the wildest confusion, our heads and our heels have reversed their normal relative positions. Dressing in an acme of haste and difficulty, I scramble on deck, where one glance reveals our position. ‘‘Typhoon?” I shout interrogatively through the uproar to the captain, who, with oil-skins streaming small Niagaras, has taken refuge for a moment under the companion hatchway, and he nods a grave, silent affirmative.

After explaining the level of dread that the word “typhoon” induced aboard a ship he recounted the experience:8

To attempt any mental occupation would, under our circumstances, have been impracticable and mere affectation. So, instead, we watch wind and sea raging with a ferocity which we are not likely ever to witness a second time. Sheltered beneath a hatchway, clinging on to a bar, whereby alone I am saved being tossed about like a tennis ball, I stare at the masses of water piled around in irregular, confused mountains. The waves seem lifted up half-way between sea and sky, and from their apex the wind, sometimes screaming, sometimes roaring so as entirely to drown the human voice, lifts up lumps of water, hurls them into the air, and then whirls them about in driving torrents of spray. Here comes a mountain towards the ship! Well, we can no more ride over it than I could run up the perpendicular walls of a house. I am persuaded that we must surely be engulfed. The ship rolls almost on its side; I cling fast, and hold my breath; the waters pour over us; some auxiliary waves strike us with a spiteful thump; she quivers in every limb; the waves sweep over the deck —

About half an hour later there was a sudden burst of activity, the steam steering-gear had broken. Crew members ran and rapid commands were given. Knollys described the importance of a skillful captain.

The steam steering-gear has broken, and we immediately roll helplessly in the trough of the sea. Several extra hands are quickly stationed at the wheel, to make good the steam machinery, and now we are able to realise the enormous advantage of being under so skilful a seaman as Captain Moodie, one of the most trusted and rising of the Peninsular and Oriental’s employés. Habitually rather taciturn and very quiet, though sharply observant, he assumes in this time of emergency active detailed command, as the master spirit whom the crew eagerly obey and whom all implicitly trust. Thus far he has been running a race with the progress of the typhoon, seeking to scrape past its edge. But now he sees that the full force of the enemy has overtaken him, and that we are no longer on the margin but in the heart, and that we are travelling in the same direction. This will never do. Keeping his footing with many a struggle on deck — a strange weird object, bare-legged, dripping with spray and perspiration — he shouts out, “Full steam ahead; four extra men at the wheel,” and “Hard a-port,” or whatever the shibboleth corresponding to the military expression “Right reverse” — as anxious a moment as might be experienced in guiding a runaway team round a sharp corner. For a few critical seconds we are one mixed-up mass of waves, foam, and ship; then we have turned our backs on the heart of the typhoon, and are flying towards its supposed frontier line.

With the hatches battened down, and no steam power for the cooling fans to fight the heat from the engine-room, the passengers occasionally opened a “crevice of the companion door” to gasp for fresh air. But water immediately poured through the aperture so they had to close it. The only option was to grin and bear the oppressive atmosphere and stifling heat until the storm settled.

The ship eventually made it out of the storm and the captain sighed with relief. “I feel as if I had lived a fortnight since yesterday,” he confided to Knollys.

WWII

During WWII, the mighty United States Pacific Fleet did not only face the Japanese navy and air force, it also battled typhoons. Especially Typhoon Cobra in December 1944 (Showa 19) caused great damage. It sank three destroyers, killed 790 sailors, damaged 9 other warships, and wrecked or swept overboard 146 aircraft.

Admiral Chester Nimitz (1885–1966) said that the typhoon’s damage “represented a more crippling blow to the Third Fleet than it might be expected to suffer in anything less than a major action.”9

The following news report describes how Typhoon Connie sheared off the bow of the heavy cruiser USS Pittsburgh in June 1945 (Showa 20). The fleet had just completed a carrier strike against Kyushu.

The danger has not gone. An average of 11 typhoons reach Japan every year.10 They bring strong winds, high waves, and heavy rainfall resulting in widespread flooding and landslides. Even today typhoons cause great damage and loss of life.

Notes

1 2011年7月の周年災害/日本の災害・防災年表(「周年災害」リンク集) 防災情報新聞 Retrieved on 2024-03-04.

2 The Far East. Vol II, No. IV. July 17, 1871, 44.

3 ibid, 44, 45.

4 ibid, 46.

5 Grossman, Michael J.; Zaiki, Masumi (2013). Documenting 19th Century Typhoon Landfalls in Japan. Review of Asian and Pacific Studies No.38, 成蹊大学アジア太平洋研究センター, 105. Retrieved on 2024-03-05.

6 Von Siebold, Philipp Franz (1897). Nippon: Archiv zur Beschreibung von Japan und dessen Neben-und Schutzländern Jezo mit südlichen Kurilen, Sachalin, Korea und den Liukiu-Inseln. Erster Band. Zweite Auflage. Würzburg, Leipzig: Leo Woerl, 34–35.

7 Knollys, Henry (1887). Sketches of Life in Japan. Chapman and Hall, 4.

8 ibid, 6–12.

9 Karig, Walter (1949). Battle report[s]. Prepared from official sources by Commander Walter Karig, USNR [and others]. Volume 5. Council on Books in Wartime, 100.

10 Grossman, Michael J.; Zaiki, Masumi (2013). Documenting 19th Century Typhoon Landfalls in Japan. Review of Asian and Pacific Studies No.38, 成蹊大学アジア太平洋研究センター, 96. Retrieved on 2024-03-05.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Kobe 1871: Battling Japan's Typhoons, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/938/1871-typhoon-kobe-kaigandori-felice-beato-vintage-albumen-print

There are currently no comments on this article.