The Great Kantō Earthquake of September 1, 1923 is the worst natural disaster in the history of Japan. It wiped much of Tokyo and Yokohama off the map and touched millions of people—just the number of people rendered homeless came to almost 2 million. The monetary estimate of the value of the destruction was four times larger than the entire national budget.

At two minutes before noon a 7.9 magnitude earthquake some 60 kilometers south-southwest of Tokyo released energy “equal to the detonation of 400 Hiroshima-size atomic bombs.”1 It was soon followed by hundreds of aftershocks, two of which almost as strong as the first one.

In an area reaching from Chiba to Shizuoka they collapsed buildings, caused a tsunami, as well as several large landslides. A landslide near Odawara pushed a train full of passengers off a cliff.

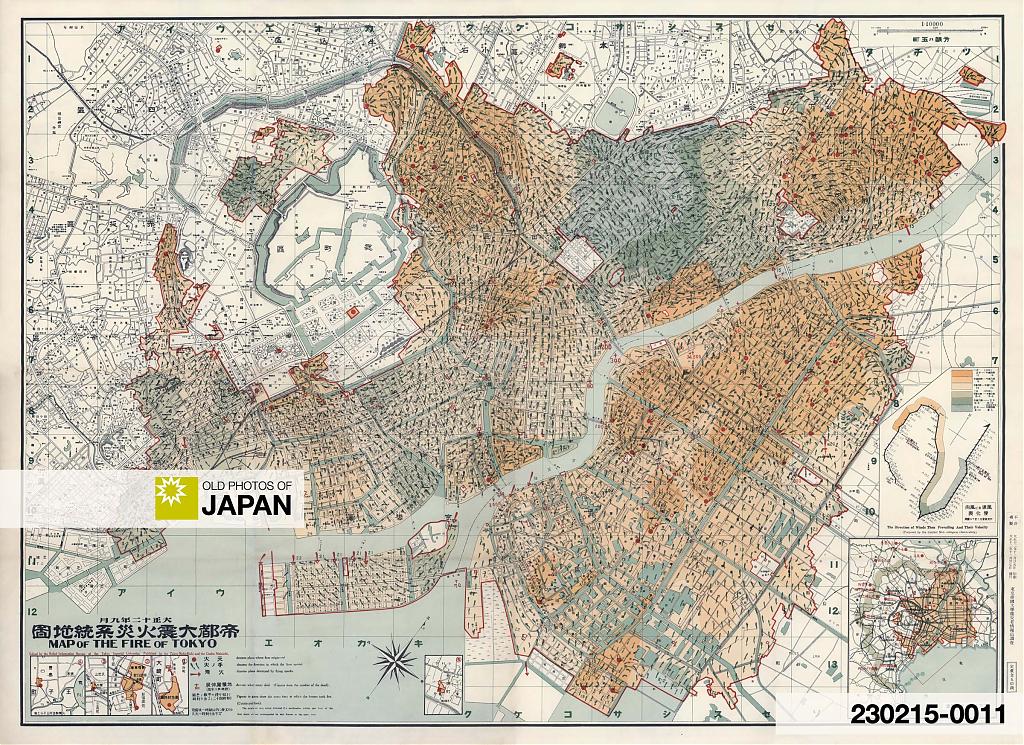

The most terrifying result of the shaking was a surge of devastating fires. Within minutes after the first shock some 134 fires spread in Tokyo alone. They were caused by overturned charcoal fires set up to cook lunch, ruptured gas lines, as well as explosions of chemicals at laboratories and drugstores as the Japan Times & Mail reported at the time:2

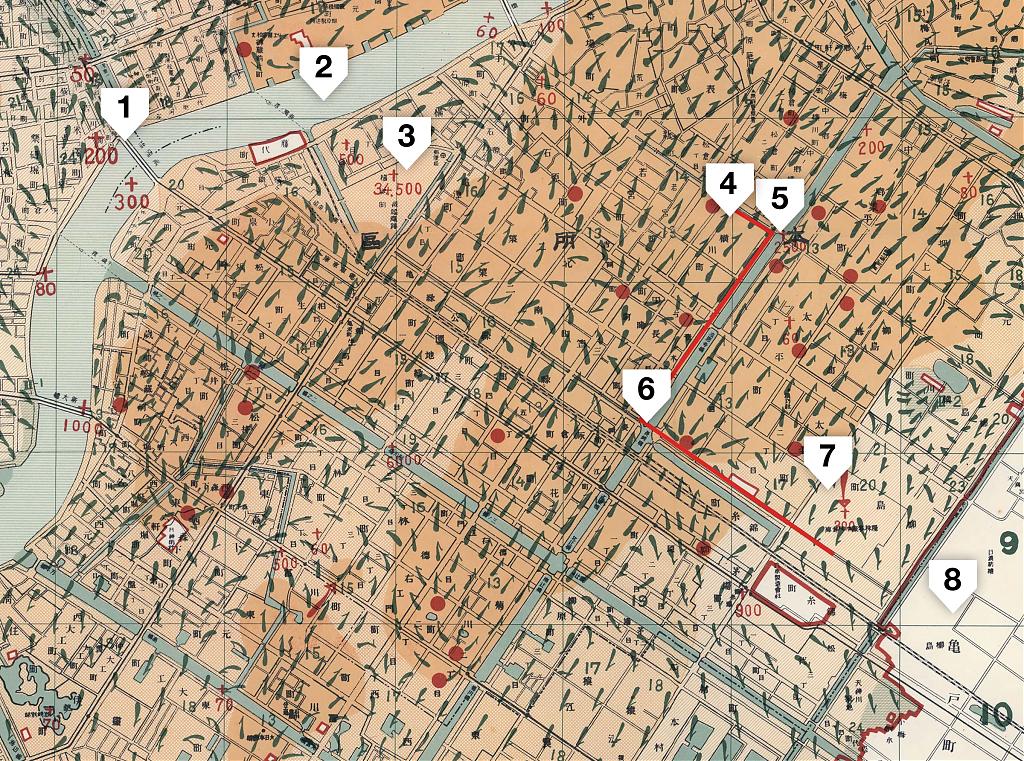

Chemicals Blamed for Starting Fire

The large number of fires almost immediately after the earthquake is now accounted for by the explosion of chemicals.

It has been ascertained that the fire which destroyed Tokyo Imperial University, the Peers School, the Higher School of Politecnics [sic] andJapan College of Dentistry, originated in each case, in the explosion of chemicals in their laboratories.

Most of the fires in Kyobashi, Nihonbashi and other wards first flame [sic] up from local drugstores. Waseda University and the Military Academy have escaped fire, but both lost their physics and chemistry laboratories, while [sic] were blown up soon after the first great shock.

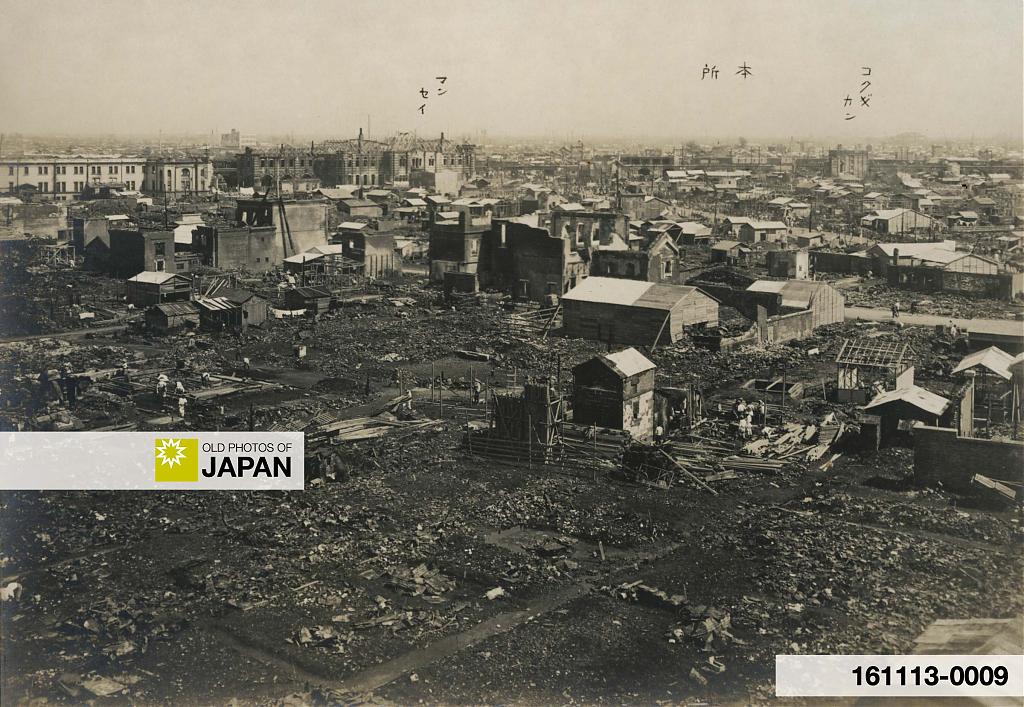

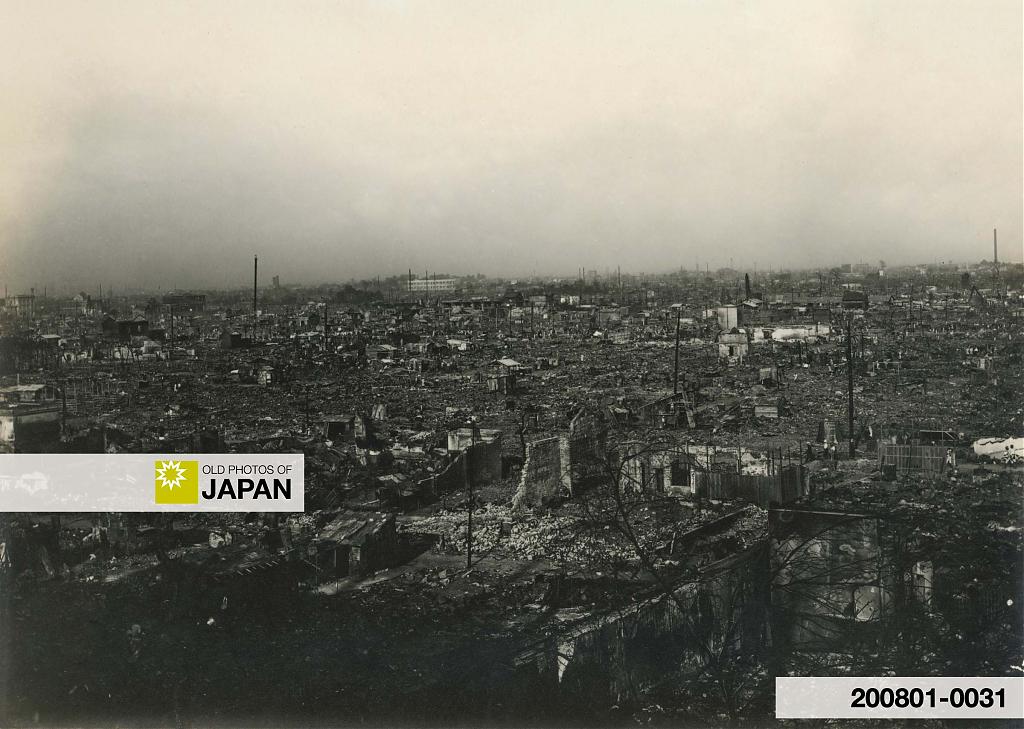

The fires turned half of Tokyo and most of Yokohama into an empty black wasteland. Almost 90 percent of the 105,000 victims of the Great Kantō Earthquake burnt to death.

One young woman documented how these fires terrified and destroyed the city around her in a detailed account of her escape. Her name was Nobu Matsumoto (松本ノブ). Nobu (1895) lived in Tokyo’s Honjo Ward (current Kōtō Ward) with her husband Tsurukichi (鶴吉, 1888?), their son Isao (伊佐雄, 1920), and daughter Shizuko (靜子, 1923).

Just before noon on Saturday September 1, the 29-year old Nobu sat down for lunch with her husband and two children. Normally she had lunch just with her children. But today her husband had a day off and they were looking forward to eating together.

They never got the chance. Within moments of sitting down their ordered life descended into unimaginable horror and chaos.3

When we picked up our chopsticks and said “well, let’s eat” the house suddenly began to shake so violently that I thought it would collapse. We threw away the chopsticks that we had just put into our hands. “Oh, a big quake! It is too dangerous to stay in the house,” I said. But the shaking was so bad that we could not stand up.

The walls of the house were falling apart, sliding doors were popping out, things were falling off the shelves, chinaware crashed. From outside Nobu heard the sound of falling roof tiles breaking into pieces, houses crumbling, and people crying and screaming. The harsh cacophony merged with the terrifying rumbling of the angry earth overwhelmed and stunned Nobu. All she could do was pray to Buddha to save them. “Namu Amida Butsu,” she chanted repeatedly.

When things settled down the family ran out of the house. Clouds of dust darkened the sky. Then another quake hit and the remaining walls and roof tiles fell down. As they made it to the street they saw that everybody in their neighborhood had fled there. Some had bloodied faces from falling tiles, others were unable to walk because of broken legs. Nobu realized that they were lucky to have escaped without injury.

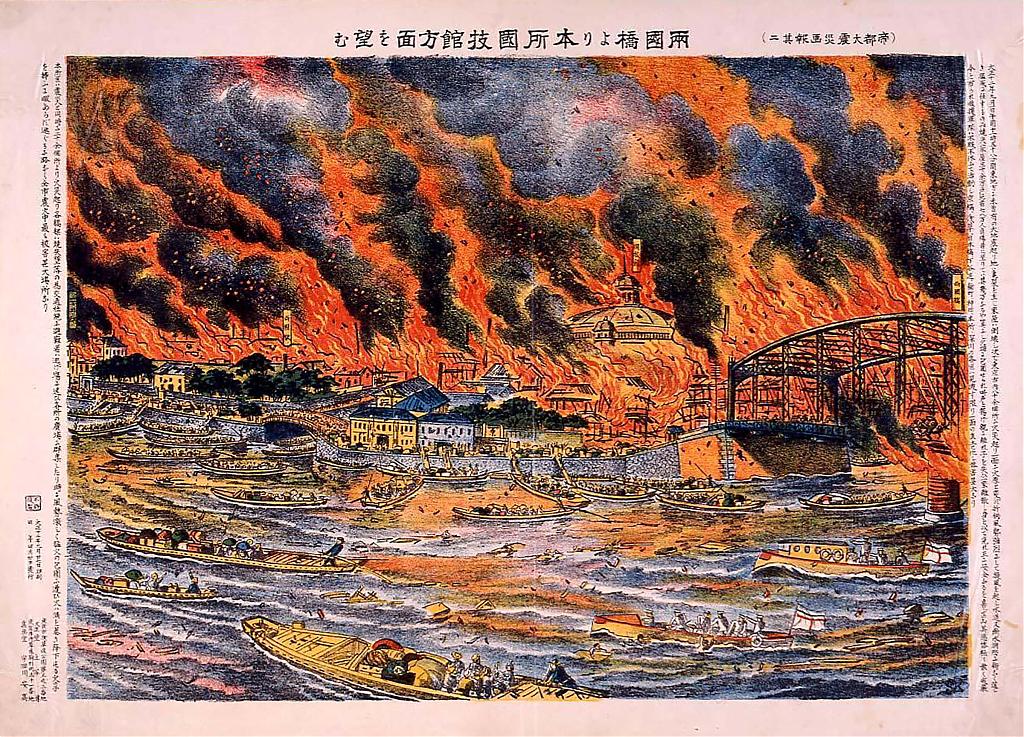

Suddenly somebody shouted “fire!” That day a typhoon was passing Japan. Because the strong wind was fanning the fires, the family quickly fled to the nearby Yokogawa Bridge (横川橋).4

We stayed there for a while, but the fires were spreading everywhere and the danger was getting closer each and every minute. The wind was raging and the flames were licking through the half-collapsed buildings like a surging tide, moving ever closer to the terrified people. Seeing this, my husband turned to me and said, “If we stay here any longer, there will be no way out. You must get away now! Take good care of the children! I must go back home to get a few things.” “OK, I will hurry. You hurry too,” I told him as we hastily parted.

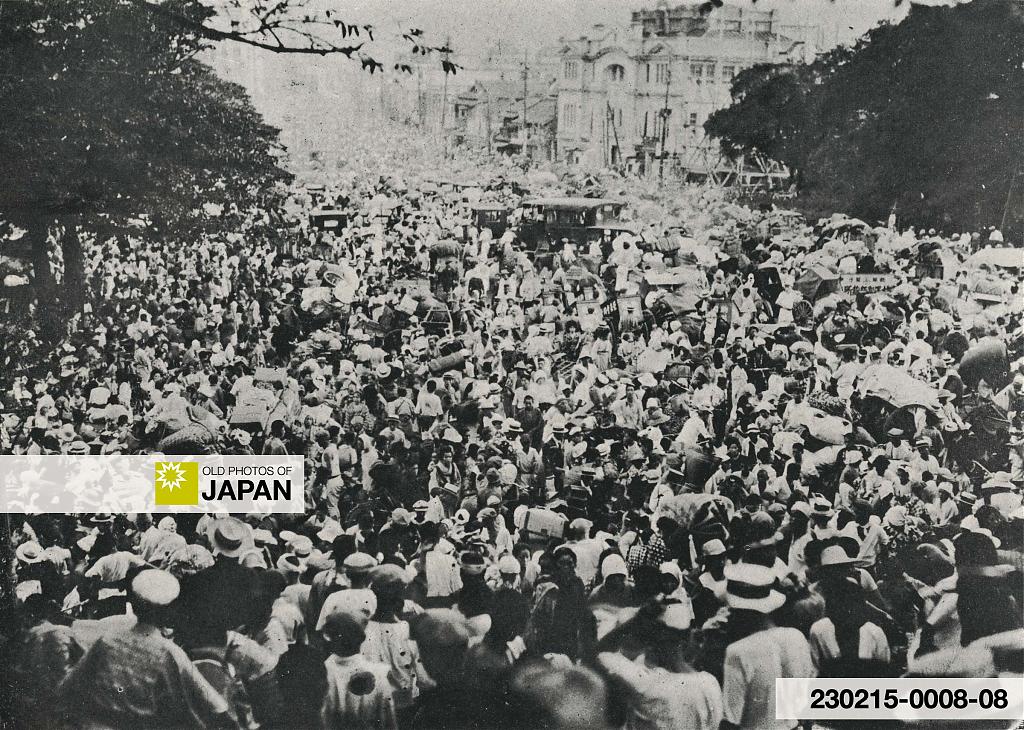

With her daughter Shizuko on her back and her son Isao by the hand, Nobu took off with the 14-year old daughter of their neighbors, Maki Yoshino (吉野まき). They were heading towards the Nagasaki Bridge (長崎橋).5 People were fleeing in all directions. Many were pulling large wooden carts overflowing with their belongings. It was chaos and nearly impossible to move.6

We finally managed to push our way through the crowds to hurriedly cross the bridge, only to find that the road was full of wrecked timber and carts filled with household goods. In the midst of it all, there were people running away with chests of drawers, people carrying bags, a horse galloping wildly into the crowd. A woman being crushed by people, a man trampled by a horse, children screaming for their parents, parents screaming for their children, sparks of fire falling like hail. The booms of buildings exploding far and near. It felt unreal.

These scenes were repeated everywhere in the disaster area. The crowds pushing, pulling and carrying their furniture and household goods clogged the roads to a standstill and made escape—and rescue—impossible. Even worse, the thousands of carts with belongings served as fuel for the hungry flames.

Pushing their way through the chaos, Nobu, Maki and the children finally managed to cross the Nagasaki Bridge. As she glanced back, Nobu saw that the area around Yokogawa Bridge was now a raging sea of fire. The sky was black with smoke. She worried about her husband.

They next went to a field at the nearby Army Food and Fodder Depot (陸軍糧秣廠, Rikugun Ryōmatsushō), a warehouse for food for soldiers and fodder for horses. Thousands of people had sought refuge here. Nobu breathed a sigh of relief and calmed down. But her feeling of safety was about to turn into sheer terror. The wind direction changed constantly and suddenly fire broke out near the depot.7

Within moments a gale so strong that I could barely breathe began to whip up clouds of dust and black smoke. I had barely exclaimed “It is a whirlwind!” when it blanketed the whole field with fire. Almost instantly all the belongings that the people had brought in and even their clothing caught on fire. Amidst all the screams erupting at once, an ear-splitting wail could be heard from the throngs of people arriving at the field. The moaning of those who were being crushed by the surging waves of people was truly a living hell. We too were surrounded by smoke and could not open our eyes or breathe. Our hair sometimes started to burn. Even the children’s kimonos caught fire.

Nobu thought that this would be the last time for her to see her children, but she would not give up. They managed to put out the fire in their hair and clothing, ran, broke through a fence, and reached a safe place. Fourteen year old Maki, seeing that Nobu was almost out of strength, rushed in to help Isao.

The four of them barely escaped with their lives. Many tens of thousands were not this lucky. Fire tornadoes like Nobu experienced at the depot were happening all over Tokyo. The worst one happened at the former Honjo Army Clothing Depot (陸軍本所被服廠, Rikugun Honjo Hifukushō), only a short distance away from the Army Food and Fodder Depot.

Some 40,000 people had sought refuge here, thinking the large open space was safe. A gigantic fire tornado burned 38,000 of them to death. With their carts full of belongings feeding the flames they had no chance of escape. It was the largest single loss of life during the Great Kantō Earthquake.

WARNING: (2) GRAPHIC IMAGES 【閲覧御注意下さい】

On this location the Tokyo Metropolitan Memorial Hall (東京都慰霊堂) was built in 1930 (Showa 5). The remains of some 58,000 victims have been enshrined here. There also is a small museum.

Nobu’s Husband

Nobu, Maki and the children eventually found shelter in the Kameido area, right next door to Honjo. Over the next few months Nobu stayed here with friends, at a school, and at a temple. She frantically searched for her husband Tsurukichi. She even visited the Yokogawa Bridge where they had parted:8

When I went to the Yokogawa Bridge, I was so shocked that the blood in my body seemed to rush to my head all at once. From the edge to the center of the bridge there was a pile of thousands of burnt corpses. The river seemed full of burnt pieces of wood, but they were dead bodies—so many that one could not see the water. Why was I not surprised? Why was I not saddened? How many thousands of people were burned to death in a single moment!? What were the thoughts of these people when they died? When I thought about this, I stood there stunned for a while in the pile of stinking corpses. But then I suddenly came to my senses when I realized that the pitiful corpse of my husband could be amongst them. With that thought in mind, I glanced here and there at the nearby corpses, but all of them had scorched and swollen faces. Even the stripes on their kimono had become indistinguishable, and in many cases I could not even tell the difference between men and women. It was not easy to recognize any of them.

Finally, in November, Nobu discovered that her husband’s body had indeed been found floating near the Yokogawa Bridge. Tokyo’s rivers were actually full of floating bodies. Many people had jumped into the water to escape the flames. Most had drowned or boiled to death. Historian J. Charles Schencking, who has written extensively about the Great Kantō Earthquake, wrote a dramatic description of such a scene:9

As he crossed the Ryōgoku Bridge, he was immediately confronted with the image of the water beneath his feet littered with bodies swollen like sumo wrestlers, bobbing up and down, back and forth in the gentle waves with charred doors, discarded belongings, and the remains of urban civilization.

This site is funded by readers like you

Old Photos of Japan provides thoroughly researched essays and rare images of daily life in old Japan free of charge and advertising. Most images have been acquired, scanned, and conserved to protect them for future generations.

I rely on readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support this work.

Postscript

Nobu’s account, and that of Gertrude Cozad, recounted on Old Photos of Japan in June, are not just memories of a terrible disaster. They are also lessons about how to survive such a disaster.

The similarities between the two accounts—one by a young Japanese mother with two children in Tokyo, the other by a 58-year old single woman in Yokohama—are astounding. Both escaped encroaching fires that killed tens of thousands. Both found a companion that gave them strength and courage. Both never gave up and kept on going until they were sure to be safe. Both based their decisions on the actual conditions that they observed around them.

By making the right decisions based on their own accurate observations they saved their own lives.

Survivors of the Great Kantō Earthquake never forgot the important lessons they learned. They taught them to their children. During a WWII air raid on Tokyo, award-winning author Akira Yoshimura (吉村昭, 1927–2006) learned such a lesson from his father who got angry when he was about to run off with his emergency backpack:10

On April 13, 1945, when Nippori was burned to the ground in a nighttime air raid, incendiary bombs fell on the back of our house and it began to burn. When I tried to leave the house carrying my emergency backpack, my father was furious. Don’t walk around with that,” he said. You must escape with only your body. When I ran toward the cemetery in Yanaka, I saw a man with a rucksack on his back who was on fire. He was trying his best to put out the fire. I thought to myself, “Ah, my father’s advice was right.” That was how strongly the Great Kantō Earthquake had impressed itself on my father.

Notes

1 Schencking, J. Charles (2008). The Great Kanto Earthquake and the Culture of Catastrophe and Reconstruction in 1920s Japan. Journal of Japanese Studies, 34:2, 299.

2 The Japan Times & Mail, September 14, 1923.

3 武村雅之(2005)手記で読む関東大震災. 古今書院, 73.

「みんなで「さあ食べましよう」と箸を取り上た時、俄かに家がたおれるかと思う程ぐらぐらぐらぐらとゆれ始めました。取った箸も投げ捨て丶、さあ大地震だ!!家に居ては危ないと言ったが、余りのゆれ方に立ち上る事さえ出来ません。」

4 ibid, 74.

「暫らく其処に居ましたが火は益々八方へ燃え広がって危険は刻々にせまって来ます。風は益々荒れ狂って火焔は潮の押し寄せる様に半ば崩れた建物をなめつくして恐れわなないている人々に迫って来ます。此の有様を見て夫は私に向い、「此処へいっ迄も居たならしまいには逃げ道がなくなるからお前は今の中に早く逃げなさい!子供に怪我でもさせない様に気を付けて!私は今一度家へ行って持って来る物があるから」と言って呉れますので「では一足お先へ逃げます。あなたも一時も早く御出で下さい」と言いながらも二人は急ぎ足に別れたのでありました。」

5 In her account Nobu mistakenly calls the Nagasaki Bridge the Utō or Kōtō Bridge.

6 武村雅之(2005)手記で読む関東大震災. 古今書院, 75.

「漸々の事に其の人波を押しのけて橋を渡り急いで行こうとすれば、道の中へ材木はたおれている、荷物を積んだ車はぎっしりある。其の中をたんすをしよって逃げて行く人、つ丶みをかついで走る人、其の混雑の中へ馬が暴れ狂って駈けて来る。人に押したおされる女、馬に踏みつぶされる男、親を呼ぶ子の悲鳴、子を呼ぶ親の叫び、火の粉は霰の様に落ちて来る。建物の爆破する響は遠く近く聞えて来る。とても此の世の様とは思われませんでした。」

7 ibid, 76–77.

「と思う間に息もつけぬ程の強風が砂塵を巻いて黒煙と共に立ち上がりました。あれつむじ風よ!!という間もなく、一同の頭上へ巻いて来て、原のまわりは一面の火となり運び込んだ荷物や人の着物に迄も燃えうつりました。一時にわっとあげる悲鳴の中に一入耳を裂く様な叫びが到れる人の群から聞こえます。崩れかかる人波のなだれに踏みつぶされる者のうめき声、実に此世ながらの生き地獄です。

私共も煙に包まれて目をあく事も息をする事も出来ません。髪の毛は時々ジリジリと燃え始めます。子供の着物に迄も時々火が付きます。」

8 ibid, 81–82.

「横川橋迄行って見ますと、此の時は身体中の血が一時に頭へ上るかと思う程驚きました。橋のたもとから橋の上のあの広場には、幾千人の焼死体が山になっているではありませんか。川の中は焼け落ちた木片でいっぱいになっているかと思えば、死体で水が見えないではありませんか。何で驚かずに居られましよう。何で悲しまずにいられましよう。あ丶此の幾千もの人々が一時に焼き殺されるだんまつまの有様は!? 此の人々の死ぬ時の思いは? と思うと、暫くは呆然として生臭い死がいの山の中につっ立っていましたが、ふと我に返って始めて、若しゃ此の中に夫も無惨の死骸となっていはせぬでしようか?と思いながら、近くにいる死人をあちらこちらとのぞいて見ましたが、何れも真黒にこげた顔はぶつくりとふくれ上って、着物の縞柄さえはっきりと見分けが着きません故、男女の区別さえ分からぬものが多くあります。まして誰かなどいふ事は容易に分かりません。」

9 Schencking, J. Charles (2008). The Great Kanto Earthquake and the Culture of Catastrophe and Reconstruction in 1920s Japan. Journal of Japanese Studies, 34:2, 301.

10 吉村昭 (2004) 日本災害情報創立5周年シンポジウム 「今、災害時の情報を問う」(要旨) Retrieved on 2023-08-20.

「昭和20年4月13日、日暮里が夜間空襲で焼き払わ れた時、家の裏に焼夷弾が落ち、燃え始めた。私が非 常持出用のリュックサックをかついで出ようとした ら、父親が激怒した。「そんなものを持って歩くんじ ゃない。身ひとつで逃げるんだ」。谷中の墓地の方へ 逃げていった時に、リュックサックを背負った男の人 が火だるまになっていた。その人は一生懸命消そうと していた。私は「ああ、父親の指示というのは正しか ったんだな」とその時思った。それほど父親は関東大 震災に非常に強烈な印象を持っていた。」

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Tokyo 1923: Drowning in a Sea of Fire, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/921/drowning-in-a-sea-of-fire

Glennis Dolce

Just devastating! So much loss. I did not know there was a museum devoted to this- will make a note to visit it next time. Thank you for this sobering remembrance of that event 100 years ago…

#000785 ·

Kjeld (Author)

@Glennis Dolce: Thank you. Yes, truly devastating, isn’t it! Having survived the 1995 Kobe quake and having covered almost all the major earthquakes in Asia since then, I have much respect for the people that went through it, like Nobu. I wish I could have met her.

#000786 ·