How 19th Century Japanese Artists Mastered the Art of Hand Colored Photography

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4

Around the World in 80 Days

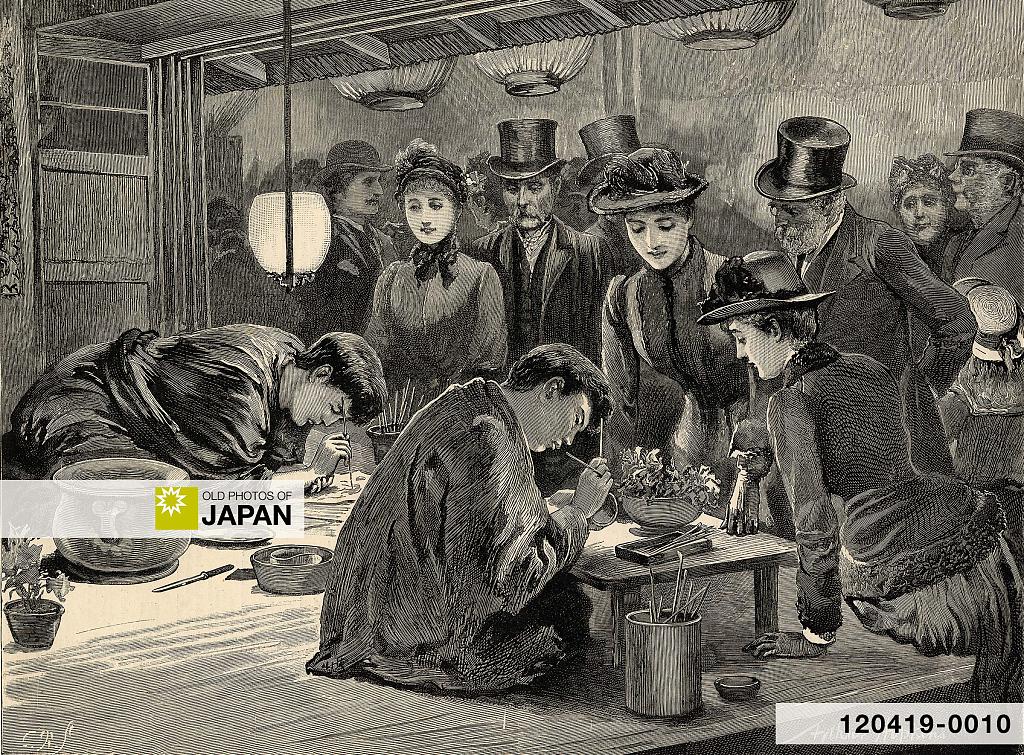

Photography was practiced across the globe, and skilled artists existed everywhere. So why did hand coloring reach such exquisite levels in Japan, and why have so many of these photographs survived?

One could attribute it to a quirk of history, or perhaps the law of cause and effect. Seemingly random historical events—occurring just in the right order and at the right time—created conditions that unleashed the extraordinary development of hand-colored photography in Japan.

The most significant of these events was the opening of Japan. After more than two centuries of self-imposed isolation, Japan opened its borders to foreign trade in 1859 (Ansei 6). Until then, a small number of Dutch traders had been the only Westerners allowed to enter Japan, and they had been confined to the tiny island of Dejima in Nagasaki.

The opening caused a sensation in Western nations. Over the following decades, an ever-increasing number of Japanese goods appeared on the shelves of shops. Galleries were filled with Japanese woodblock prints and other artworks. There were special exhibitions, even recreated Japanese villages.

The wave of imports launched Japonisme and influenced exciting new movements in the arts and architecture. The refreshingly new Japanese aesthetic inspired the likes of Vincent van Gogh, Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Mary Cassatt, James McNeill Whistler, Frank Lloyd Wright.

The admiration for all things Japanese was boundless. Many imagined a traditional and harmonious culture with natural landscapes untouched by industrialization and modernization. Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) expressed this idealized vision in a letter he wrote to his brother Theo in 1888 (Meiji 21):47

If we study Japanese art, we see a man who is undoubtedly wise, philosophic and Intelligent, who spends his time how? In studying the distance between the earth and the moon? No. In studying the policy of Bismarck? No. He studies a single blade of grass. But this blade of grass leads him to draw every plant and then the seasons, the wide aspects of the countryside, then animals, then the human figure. So he passes his life, and life is too short to do the whole. Come now. Isn’t it almost an actual religion which these simple Japanese teach us, who live in nature as though they themselves were flowers? And you cannot study Japanese art, It seems to me, without becoming much gayer and happier, and we must return to nature in spite of our education and our work in a world of convention.

An ever growing fascination with this newly discovered and seemingly unspoiled civilization had been ignited. Japan was ultra-cool.

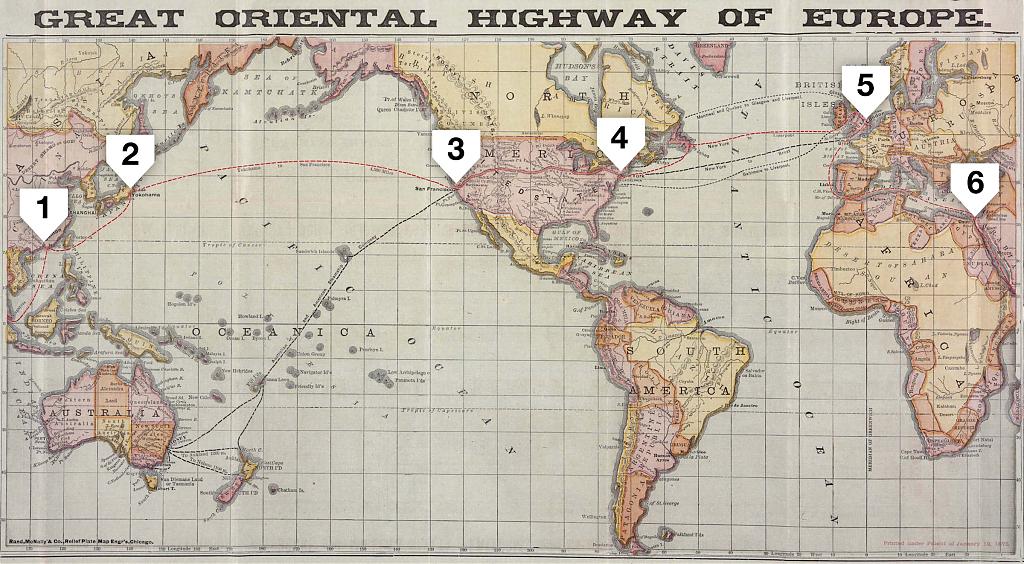

It may have been cool, it was also far away and incredibly hard and costly to reach. A cascade of technological innovations was about to change this dramatically. Only a decade after Japan opened its doors, telegraphy, steamships, and trains had completely transformed global travel and trade. Suddenly Japan was within reach.

It is hard to overstate this transformation. When Japan opened its borders in 1859 it took over four months to exchange letters with Britain, then the commercial center of the world. After Japan was linked to the global telegraphy network in 1870 (Meiji 3) responses could be received within hours.

The impact of steamships and trains, and the opening of the Suez Canal and the trans-American railroad in 1869 (Meiji 2), was just as great. Travel time between Japan and the West was reduced from many months to several weeks.

The 1872 (Meiji 5) edition of Disturnell’s Railroad and Steamship Guide could barely conceal astonishment at the drastic transformation that had taken place:48

A traveller or business man who, a few years ago, went to San Francisco, Japan, China or India, or made the circuit of the globe, arranged his affairs with the expectation that at least a year or two of his life was required to make the journey by land and water. To-day he can start from New York or London, transact important business, and enjoy the pleasures of travel, returning to his home, if desired, within the period of three months; during which time he is in communication with the chief centres of business by telegraph and steam post-routes.

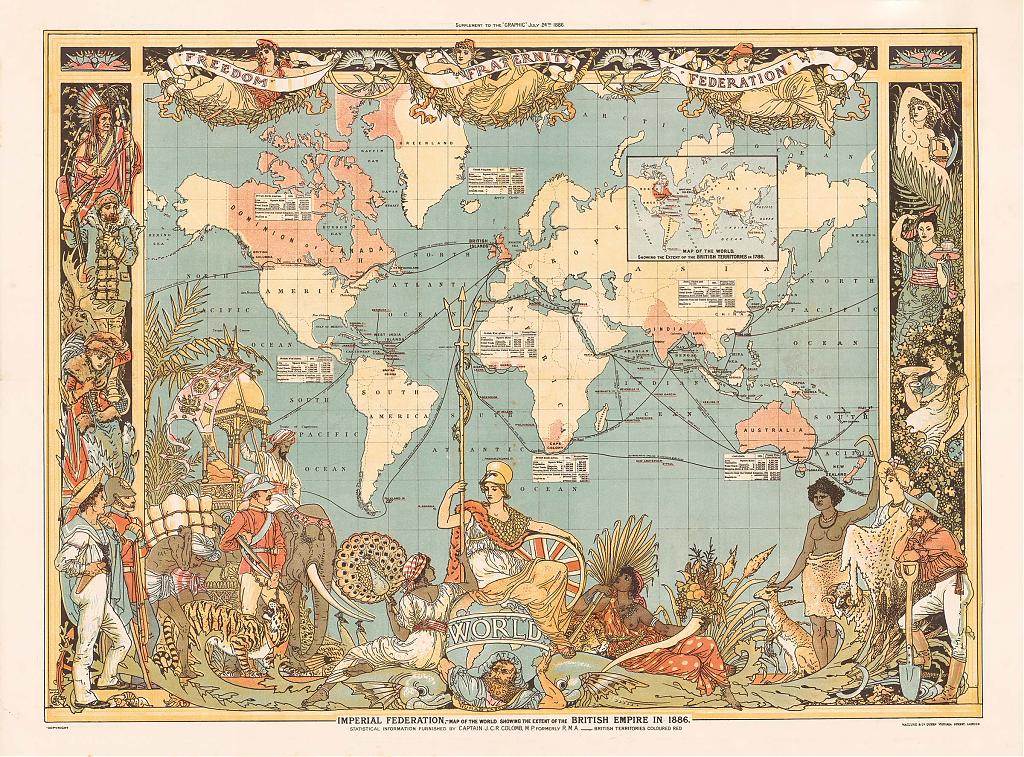

All these changes took place just as British power was at its peak. Great Britain acting as the global policeman had ushered in an era of relative stability, making international travel safer than it had ever been.

British travel entrepreneur Thomas Cook (1808-1892) was one of many who saw the opportunities of this global transformation. In 1872, he led the first-ever package tour around the globe, dramatically showcasing this brave new world.

Cook had barely returned when French author Jules Verne (1828–1905) published Around the World in 80 Days. The book became an international bestseller and put the idea of a trip around the world in the heads of people who had previously never even imagined it.

The age of the globetrotter had begun. For the first time in history large numbers of tourists started traveling around the world. Japan was on the top of the list of these new world travelers. Everybody wanted to see this entrancing fairytale land. And they all wanted memorable souvenirs.

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1859 | Japan opens borders to foreign trade. |

| 1861 | West Coast of the United States connected to the East Coast by telegraphy. |

| 1866 | Telegraphy cable laid across the Atlantic Ocean. |

| 1867 | First regularly scheduled trans-Pacific steamship service—by the Pacific Mail Steamship Company between Hong Kong, Yokohama, and San Francisco. |

| 1869 | Suez Canal opened. Ships no longer have to go all the way around Africa. First transcontinental railroad in the United States. No need to travel around South America. |

| 1870 | Indian railways linked across the sub-continent. Britain and India reliably connected by telegraphy. Japan connected to the international telegraph network. |

| 1872 | Thomas Cook departs on the first package tour around the world. Japan's first railway opened between Yokohama and Tokyo. |

| 1873 | Jules Verne publishes Around the World in 80 Days. |

New Markets

When Beato first started out in Yokohama in 1863 his customers were mainly foreign residents: merchants, missionaries, military officers, diplomats. The ever increasing number of globetrotters that started to visit Japan from the 1870s, opened up a completely new and exceptionally lucrative photography market: lavish albums with souvenir photos, as well as studio portraits in Japanese clothing.

These albums did not only function as souvenirs, but also as gifts between international associates—upscale corporate gifts inscribed with dedications.49

Business was not limited to Japan. People who could not afford to travel to Japan were just as fascinated by the country and a thriving export market developed. The same steamboats and trains that brought the globetrotters made it possible to transport the photographs relatively quickly and affordably from Japan to markets on the other side of the world.

The result was an intensely enterprising and competitive photographic industry catering to a seemingly insatiable global market. It allowed hundreds of traditionally trained Japanese artists to develop their photo coloring skills to heights unequaled in other countries.

This professional souvenir photograph market reached its peak during the 1890s after which it started to collapse. One cause was Eastman Kodak‘s popular compact and portable film camera which allowed visitors to take their own photos. Another was new printing technology that gave birth to mass-produced low-cost postcards.

At first these were also hand colored, but in the 1920s color increasingly vanished. Monochromatic photographs and postcards became the norm. The age of hand colored photography came to an end and the once so popular Yokohama studios disappeared forever.

Today, more than a century later, large numbers of these beautifully hand colored photographs still pop up in auctions. While countless numbers of photos in Japan itself were destroyed by earthquakes, fires, war, or the humid climate, the souvenir photographs survived.

They survived precisely because they were souvenirs. They were taken abroad and preserved as valuable personal memories in well-protected, sturdy, and often expensive albums that were cherished and cared for.

This site is funded by readers like you

Old Photos of Japan provides thoroughly researched essays and rare images of daily life in old Japan free of charge and advertising. Most images have been acquired, scanned, and conserved to protect them for future generations.

I rely on readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support this work.

Postscript — Legacy

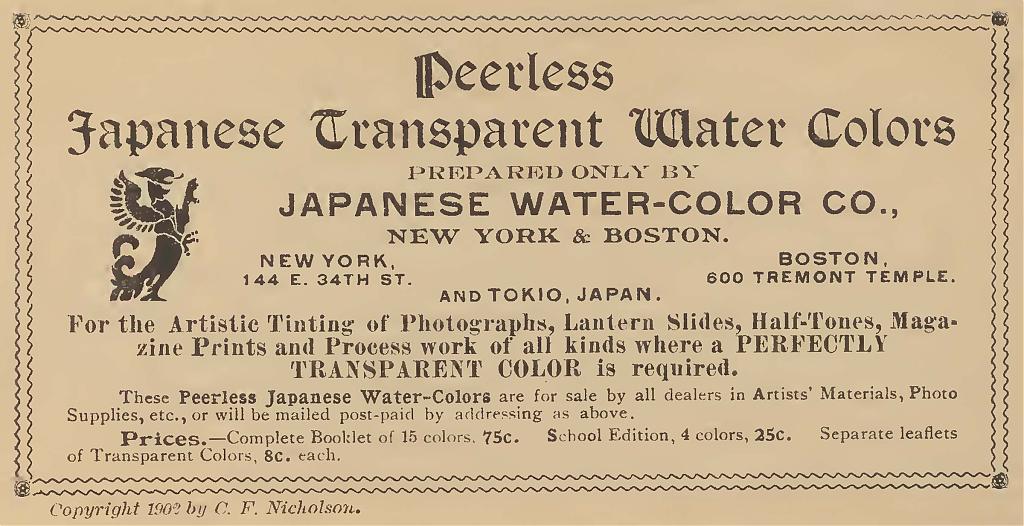

Amazingly, there is a small living legacy of these 19th century hand colored photographs from Japan. Ever since Boston-based publisher J.B. Millet printed the multi-volume Japan: Described and Illustrated by the Japanese in 1896 (Meiji 29) with hundreds of thousands of photographs hand colored by Japanese artisans, Americans associated top-class hand coloring unequivocally with Japan.

This persuaded a New York and Boston based company to brand their water colors Peerless Japanese Transparent Water Colors.50 The product’s instructional text stated that “the art of transparent tinting had its origin in Japan and the wonderful skill of the Japanese artists in this line of work has excited universal admiration.”

The product is still produced today, and is much loved by artists. The word Japanese however is no longer part of the name.

| TIMELINE | |

|---|---|

| 1839 | Louis Daguerre announces the daguerreotype. |

| 1849 | Shimazu Nariakira purchases a camera imported through Dejima. |

| 1856 | Dr. Van den Broek starts teaching photography. |

| 1857 | Ichiki Shirō creates a discernible image with Shimazu's camera. |

| 1859 | Japan is opened to foreign trade. Pierre Rossier instructs Japanese photography students in Nagasaki. |

| 1863 | Felice Beato arrives in Japan and starts selling hand colored photographs. |

| 1871 | Raimund von Stillfried opens his studio and refines Beato's commercial and artistic practices. Over the following years many of his assistants, including Usui and Kimbei, start their own studios. |

| 1870s | Globetrotters start visiting Japan in ever growing numbers, creating a lucrative market for hand colored photographs. An export market is also developed. |

| 1880s | Intense competition between studios. Colored topographical souvenir photographs become the norm. |

| 1890s | Height of the professional hand colored souvenir market. |

| 1910s | Hand colored souvenir photographs disappear from the scene. |

List of Photographers

The table below lists the photographers mentioned in this essay. OPJ links to a photographer’s images on this site, while MS links to a photographer’s work on my more elaborate archival site MeijiShowa.

| Name | Japanese | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Ichiki Shirō (1828–1903) |

市来四郎 | Photographed daimyō Shimazu Nariakira in 1857, the oldest known daguerreotype by a Japanese. |

| Hikoma Ueno (1838–1904) MS |

上野彦馬 | Studied at Dejima. One of the first professional Japanese photographers. Based in Nagasaki. |

| Kuichi Uchida (1844–1875) OPJ | MS |

内田九一 | Studied at Dejima. In 1872 , Uchida became the first person to officially photograph Emperor Meiji and Empress Shōken. |

| Pierre Rossier (1829–1886) |

ピエール・ロシエ | Helped the Japanese photography students in Nagasaki overcome the last remaining obstacles. |

| Felice Beato (1832–1909) OPJ | MS |

フェリーチェ・ベアト | First photographer in Japan to start coloring prints on a large scale. |

| Raimund von Stillfried (1839–1911) OPJ | MS |

ライムント・フォン・シュティルフリート | Took over Beato's studio and refined his practices. Many of his Japanese assistants opened their own photography studios. |

| Shūzaburō Usui (dates unknown) OPJ | MS |

臼井秀三郎 | Studied with Stillfried before opening his own studio, one of the first to also color topographical views. |

| Kimbei Kusakabe (1841–1934) OPJ | MS |

日下部金兵衛 | Worked as colorist for Beato and probably Stillfried. Opened his own studio between 1878 and 1880. Published a vast number of colored photographs. |

| Kōzaburō Tamamura (1856–1923?) OPJ | MS |

玉村康三郎 | Commercially most successful Japanese photographer of the 19th century. Exported over 400,000 hand colored prints to the Boston publishers J.B. Millet. |

| Kazumasa Ogawa (1860–1929) OPJ | MS |

小川一眞 | Pioneer in photomechanical printing. Introduced collotype printing to Japan. Ogawa's colored flower collotypes still impress today. |

| Adolfo Farsari (1841–1898) OPJ | MS |

アドルフォ・ファルサーリ | Marketed expensive high quality hand colored prints. |

| Nobukuni Enami (1859–1929) OPJ | MS |

江南信國 | Mastered photographic media from prints to lantern slides to stereoviews. High standard of hand coloring. Traded as T. Enami. |

| Teijiro Takagi (dates unknown) OPJ | MS |

高木庭次郎 | Took over the Kobe branch of Kōzaburō Tamamura. Published large numbers of colored collotype books and lantern slides. |

Naturally, many other photographers played a role in the history of Japanese photography. This essay’s aim is to introduce the most important people directly leading to the large output of hand colored photographs in the late 1800s which were mainly aimed at a foreign clientele and the international market.

If you would like to know more about the history of early photography in Japan, and all of these other photographers, I recommend Photography in Japan 1853–1912 by Terry Bennett (2006).

Kimbei Catalogue

How crucial colored topographical views were for Kimbei’s business becomes clear from a rare printed catalogue of his studio dating from around 1893 (Meiji 26). Almost 70% of the listed photographs are topographical views.

| Subject | Images | % |

|---|---|---|

| Costumes | 460 | 30.8% |

| Yokohama | 111 | 7.4% |

| Tokyo | 148 | 9.9% |

| Nikko | 159 | 10.6% |

| Ikao, Ashio, Mt. Fuji | 77 | 5.2% |

| Miyanoshita, Hakone | 79 | 5.3% |

| Enoshima, Kamakura, Atami, Mitake | 73 | 4.9% |

| Nakasendo | 69 | 4.6% |

| Kobe, Osaka, Lake Biwa, Nara | 86 | 5.8% |

| Kyoto, Miyajima, Matsushima | 87 | 5.8% |

| Nagasaki | 54 | 3.6% |

| Earthquake Views | 24 | 1.6% |

| 17x22 Inch Photos | 66 | 4.6% |

| SUBTOTAL | 1,493 | 100% |

| Other | 190 | |

| Unnumbered | 99 | |

| TOTAL | 1,782 |

As an interesting side note, Kimbei always advertised that he offered over 2,000 views but the catalogue features only 1,493 entries in total (including variations of the same title). Over several years of research I have already found almost 300 images that are not listed in the catalogue, so the number in Kimbei’s ads might have been true.

Kimbei’s biographer, Hirotoshi Nakamura (中村啓信), has called him “the giant of color photography in the Meiji period” (明治時代カラー写真の巨人).51 This seems true for both quality and volume. According to an estimate by Japanese historian Takio Saitō (斉藤多喜夫) Kimbei prints account for over sixty percent of the extant Japanese souvenir photos from Yokohama.52

Selected Bibliography

- Bennett, Terry (2006). Old Japanese Photographs: Collectors’ Data Guide. Bernard Quaritch Ltd.

- Bennett, Terry (2006). Photography in Japan 1853–1912. Tokyo, Rutland, Singapore: Tuttle Publishing.

- Bennett, Terry (2006). Pierre Joseph Rossier (1829-1886) – Pioneer Photographer In Asia.

- Beretta, Lia (1996). Adolfo Farsari: An Italian Photographer in Meiji Japan in The Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, Fourth series, Vol. 11.

- Brendon, Piers (1991). Thomas Cook: 150 Years of Popular Tourism. London: Secker & Warburg.

- Dobson, Sebastian et al (2004). Yokohama Sashin in Art and Artifice: Japanese Photographs of the Meiji Era. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts.

- Ewer, Gary W. The Daguerreotype: An Archive of Source Texts, Graphics, and Ephemera.

- Gartlan, Luke (2016). A Career of Japan: Baron Raimund Von Stillfried and Early Yokohama Photography. Leiden – Boston: Brill.

- Gartlan, Luke (2017-07-20), Postcards from a picture-perfect Japan.

- Henisch, Heinz K; Henisch, Bridget Ann (1996). The painted photograph, 1839-1914 : origins, techniques, aspirations. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Hight, Eleanor M.; Sampson, Gary D. (2002). Colonialist Photography: Imag(in)ing Race and Place. London: Routledge.

- Himeno, Junichi et al (2005). Reflecting Truth: Japanese Photography in the Nineteenth Century. Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing.

- Hockley, Allen (2008). Globetrotters’ Japan: Places. Foreigners on the Tourist Circuit in Meiji Japan. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Visualizing Cultures.

- Iwasaki, Haruko (1988). Western Images, Japanese Identities: Cultural Dialogue between East and West in Yokohama Photography in A Timely Encounter: Nineteenth-Century Photographs of Japan. Peabody Museum Press.

- Johnston, Cara (2004). Hand-Coloring of Nineteenth Century Photographs. The Cochineal.

- Lacoste, Anne (2010). Felice Beato: A Photographer on the Eastern Road. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

- Lehmann, Ann-Sophie (2015). The Transparency of Color: Aesthetics, Materials, and Practices of Hand Coloring Photographs between Rochester and Yokohama. Getty Research Journal No. 7.

- Mac Lean, J. (1978). The Significance of Jan Karel van den Broek (1814-1865) for the Introduction of Western Technology into Japan, Japanese Studies in the History of Science (16), History of Science Society of Japan 1978-03.

- Moeshart, Herman J. (2009). Dr. Jan Karel van den Broek as Teacher of Photography, Old Photography Study No. 3.

- Oechsle, Rob. T-Enami.org.

- Tani, Akiyoshi et al (2018). Japan in Early Photographs: The Aimé Humbert Collection at the Museum of Ethnography, Neuchâtel. Stutwagnertgart: Arnoldsche Art Publishers.

- Van den Broek, Jan Karel (1893). Uit de laatste dagen van het gesloten Japan, door den heer J. K. van den Broek. Tijdschrift voor Nederlandsch Indië, 22e jaargang, Eerste aflevering, Januari 1893.

- Wagner, Sarah S. et al (2001). The Hand-Coloring and Retouching of Photographic Prints: An Annotated Bibliography in Topics in Photographic Preservation, Volume 9.

- Wakita, Mio (2013). Sites of “Disconnectedness”: The Port City of Yokohama, Souvenir Photography, and its Audience. The Journal of Transcultural Studies, 4(2), 77–129.

- Wakita, Mio (2013). Staging Desires: Japanese Femininity in Kusakabe Kimbei’s Nineteenth Century Souvenir Photography. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag GmbH.

- Winkel, Margarita (1991). Souvenirs from Japan: Japanese Photography at the Turn of the Century. London: Bamboo Publishing Ltd.

- Worswick, Clark (1979). Japan Photographs 1854—1905. New York: Penwick Publishing Inc. and Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

- 中村 啓信 (2006). 明治時代カラー写真の巨人 日下部金兵衛. 国書刊行会.

- 松本 逸也 (1993). 幕末漂流. 人間と歴史社.

- The British Journal of Photography.

- Journal of the Photographic Society of London.

Notes

47 Roskill, Mark (1967). The letters of Vincent Van Gogh. New York: Atheneum, 295.

48 Disturnell’s Railroad and Steamship Guide: Around the World in Ninety Days, by Rail and Steam (1872). Philadelphia: W.B. Zieber, 113.

49 Gartlan, Luke (2016). A Career of Japan: Baron Raimund Von Stillfried and Early Yokohama Photography. Leiden – Boston: Brill, 205.

50 Lehmann, Ann-Sophie (2015). The Transparency of Color: Aesthetics, Materials, and Practices of Hand Coloring Photographs between Rochester and Yokohama. Getty Research Journal No. 7, 81-96. Retrieved on 2023-03-25.

51 中村 啓信 (2006). 明治時代カラー写真の巨人 日下部金兵衛. 国書刊行会.

52 Wakita, Mio (2013). Staging Desires: Japanese Femininity in Kusakabe Kimbei’s Nineteenth Century Souvenir Photography. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag GmbH, 44.

Glennis Dolce

I actually have a booklet of these Peerless watercolors I came across in a box of my great grandparents things! Interesting to know they were developed as a result of hand coloring photos.

#000764 ·

Kjeld (Author)

@Glennis Dolce: Oh, how cool, Glennis! Is there a date on the booklet? And are there also colored photographs among their belongings?

#000765 ·

Kjeld (Author)

@Glennis Dolce: If you are interested in more detailed information about the Peerless Watercolors, please read The Transparency of Color: Aesthetics, Materials, and Practices of Hand Coloring Photographs between Rochester and Yokohama.

#000766 ·

Karl Michalski

WOW, very beautiful!

#000773 ·

Kjeld (Author)

@Karl Michalski: Thank you.

#000774 ·