A Japanese family poses stoically to “celebrate” a male family member being sent off to war during the late 1930s, or early 1940s. The banners bear his name.

When one was conscripted for the Japanese military during the 1930s and 1940s, a red colored draft order (臨時召集令状, rinji shōshū reijō) was delivered. Because of its color, the order was colloquially known as a red paper (赤紙, akagami). The akagami were personally delivered. The records needed for the conscription were collected and kept by over 10,000 military-affairs clerks all over Japan, covering even the country’s smallest hamlets.1

These clerks kept extremely detailed records of all the men eligible for call-up. In Japan at War: An Oral History (1992), former military-affairs clerk Shigenobu Debun, who was based in Toyama Prefecture, shows the interviewer such a record:2

In 1925, this man, Hakusan Shinichi, took the conscription examination. He was rated Class A in his physical—that is, in the best qualified group. He was assigned to the infantry. He was appointed an infantry second lieutenant in 1927. At that time, he was placed on the reserve list, having completed his active duty. In the next column, reserved for remarks, we can see he was mustered again for the Pacific War, called up in 1944, and served in Unit 48 in Japan’s Eastern Region. That is the most basic information. But the next column gives the address of the person to whom that second draft notice was delivered. Ōkado 1229 was the address of his father, Hakusan Jisaku. The responsibility was thus clearly assigned to the father. He was the one who received the red call-up paper. His obligation to inform his son was defined by law. If his wife was there, in the absence of a man, she would have had to convey the news to her son. If she did not discharge this responsibility, she would be charged under military penal law. The government undertook to pay the person’s transportation back to Toyama from wherever he was when he was informed of his call-up. The actual military unit that was responsible for paying that fee was recorded on the red paper itself.

To ensure that they would never end up with empty hands, military-affairs clerks like Debun endeavored to know everything about the eligible men and their families. Debun explains how he sent extensive reports to the military—“the soldier’s family background, whether it included a criminal or not, the size of the family’s rice fields, the value of their properties.”3

I often walked around in the village to learn what the villagers were up to. Even those walks belonged to the realm of military secrets. I couldn’t say, “I came to check on you,” so I’d just ask, “Your son who’s working in Osaka as a barber—how’s he doing?” In that way I would find out. Then I’d send a letter directly to the man. A person couldn’t really lie about their physical condition, in a time of war, so he’d write back, “I’m fine.” They always responded like that, without fail. Even those who were classified Class C wouldn’t get a doctor to write they had infection of the lungs or whatever. Each man knew how to behave. This was wartime.

Notifications were delivered to the village police chief of Debun’s village in the middle of the night. They were opened in the presence of the mayor. Debun then delivered them personally, often very early in the morning. Even before 5 a.m.

The send-offs of soldiers—wherever they happened in Japan—were ostentatious occasions. Banners with exhortations and the name of the particular soldier were raised in front of his house. Family, friends, and neighbors came to “congratulate” him. There were speeches in front of the house, after which the man often walked together with other conscripted men to the town hall, a school, or other official building. Because the streets were crowded with people carrying name banners and flags, it looked like a festive event.

At the government building, the mayor and other influential people of the town greeted the new soldiers. They “congratulated” each person in turn, exhorting them to do their best on the battle field.

Then, the soldiers spoke, saying that they would do their best for the country. At the end of the ceremony everybody shouted “banzai” three times and a brass band played military marches. There was even a march called Song for Seeing Soldiers Off to War (出征兵士を送る歌, Shussei Heishi o Okuru Uta).

This clip plays this nationalistic song. It shows Japanese conscripts going off to war, the community supporting them, and scenes from the 2011 war movie The Flowers of War, depicting Chinese and Japanese forces fighting at Nanking, China in 1937 (Showa 12).

The festival atmosphere was dispensed with In advance of the attack on Pearl Harbor of December 1941. Extreme secrecy was employed when preparations began in July of that year.4

We were ordered to call up men, but they were to report carrying a fishing rod, or with a beer or cider bottle from their belts, and dressed in a light summer kimono. Those instructions weren’t indicated on the draft notice. They came on a separate sheet. I thought something was strange, but I knew immediately that it was a military secret. We couldn’t even send these people off at the station in broad daylight as we’d done for the war with China. But we had a sending-off ceremony at the school.

The secrecy returned during the last years of the war. There were many restrictions on seeing off soldiers at train stations and the use of ceremonial flags and banners.5

Wishes and Prayers

There were two things that every departing soldier received. Both of them represented the wishes and prayers of family, friends and the community—none of whom could openly express their distress and worries—while simultaneously uniting the country in the war effort.

One was the senninbari (千人針, thousand person stitches), a long strip of white cloth of about a meter long embroidered with a thousand knotted stitches that looked like little balls. Known as tama musubi (玉結び), they were generally stitched with red thread. This color combination was deliberate, as the combination of red and white has traditionally been considered lucky and auspicious in Japan.

The senninbari were made by mothers, sisters, wives, and members of the Patriotic Women’s Association (愛国婦人会, Aikoku Fujinkai). They would go to crowded places like temples, train stations and department stores to ask female passersby to sew in a knot.

As an exception, women born in the year of the tiger could make as many knots as their age. This was based on the proverb that a tiger travels far but always returns (千里を行き、千里を帰る, senri ni iki, senri o kaeru). The many knots of the tiger women were supposed to help the soldier achieve this as well. For the same reason, many senninbari had the stitches follow the design of a tiger instead of straight lines.

Occasionally, 5 or 10 sen coins were also sewn in. This originated from a wordplay. Four sen (四銭) is pronounced shisen in Japanese. This is a homophone of the word for the borderline between life and death (死線). So the 5 sen coin expressed the wish to be safely carried beyond that borderline. Nine sen (九銭, kusen) is a homophone of the word expressing a hard struggle (苦戦). Sometimes, protective charms from shinto shrines were also sewn in.

The cloths were a tangible expression of the women’s desire for the men in their life to return home safely. It was said that the senninbari would protect the wearer on the battle field, and many soldiers treated them as a protective charm. They generally wrapped the cloth around their waist, or sewed it into their hat or helmet.

One wonders how many soldiers actually believed that the senninbari would protect them. The soldiers more likely saw them as something that connected them to their homes and families. In one oral history study, a person recalls how his brother was conscripted in 1939 (Showa 14). He specifically mentions senninbari:6

The night before he departed, family and friends gathered for a ceremony. Many brought sake and mochi, the customary drink and snack for such occasions. During the send-off, it was common practice for the mothers and wives of soldiers to drink sake while praying to the Guardian God for the soldier’s safe return. Everyone encouraged my brother to do his best for the country and for the emperor, but the truth was we really just wanted our brother to come back home alive. During the ceremony, he was given the traditional “thousand-stitch” spiritual belt [senninbari] to ward off enemy bullets. He wrapped it around his waist dutifully. There is nothing as pitiful as a thousand-stitch belt, because it had no effect, and we all knew it. The women made them with sadness.

There was a song for senninbari as well, Aikoku Senninbari (愛国千人針, Patriotic Thousand Person Stitches), released in 1937 during the Second Sino-Japanese War. In this clip of women collecting stitches on the street, you can hear part of the song as sung by Junko Mikado (三門順子, 1915–1954).

Senninbari have become symbolic for the period between the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 (Showa 6), and the end of the Pacific War in 1945 (Showa 20). But this custom existed long before these conflicts.

It is believed to have started during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895). During the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905)—when they were used as bullet-dodging amulets—the custom was already practiced in many areas of Japan.

At this time they were also known as sennin musubi (千人結び, thousand person knots) or sennin chikara (千人力, thousand person power). Senninbari became the standardized name during the 1930s and 1940s.

Interestingly, during the Russo-Japanese War, the Japanese government labelled folk beliefs like this as superstitions and discouraged them. From the 1930s on, however, the government greatly encouraged them. The beliefs were now seen as an effective way to promote nationalism and a warlike spirit, and the practice of senninbari was widely reported in newspapers and other media.

In 1937, even a movie titled Senninbari was released. In this film a mother makes a senninbari for her estranged son before he goes off to war in China. The movie was lost in the chaos of war, but in the late 1990s a partial print was discovered in Russia. It is the oldest surviving Japanese color sound film.7

The second thing that every departing soldier received was the yosegaki hinomaru (寄せ書き日の丸), a Japanese national flag signed by family, friends, neighbors and colleagues. Often it featured brief messages from them as well. Generally, the flag also contained the soldier’s name and an exhortation—a common one was may your military fortunes be long lasting (武運長久, Buun Chōkyū).

It is believed that this custom started sometime in the mid-1930s or during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). Just as was done with the senninbari, soldiers generally carried their yosegaki hinomaru with them onto the battlefield. The flags became coveted trophies amongst allied troops.

United States Marine Eugene Sledge, immortalized in the popular 2010 HBO miniseries The Pacific, described in his WWII memoirs the first time he saw American soldiers take these flags from fallen Japanese soldiers.8

He then removed a Nambu pistol, slipped the belt off the corpse, and took the leather holster. He pulled off the steel helmet, reached inside, and took out a neatly folded Japanese flag covered with writing. The veteran pitched the helmet on the coral where it clanked and rattled, rolled the corpse over, and started pawing through the combat pack. The veteran’s buddy came up and started stripping the other Japanese corpses. His take was a flag and other items. He then removed the bolts from the Japanese rifles and broke the stocks against the coral to render them useless to infiltrators. The first veteran said, “See you, Sledgehammer. Don’t take any wooden nickels.” He and his buddy moved on. I hadn’t budged an inch or said a word, just stood glued to the spot almost in a trance. The corpses were sprawled where the veterans had dragged them around to get into their packs and pockets. Would I become this casual and calloused about enemy dead? I wondered. Would the war dehumanize me so that I, too, could “field strip” enemy dead with such nonchalance? The time soon came when it didn ‘t bother me a bit.

The deaths of these Japanese soldiers, far away from home at places their families had never heard of, in miserable circumstances they could scarcely have imagined, were reported as heroic deeds by Japan’s news media.

In the late 1980s, former WWII military correspondent Uichirō Kawachi told historians Haruko Taya and Theodore F. Cook how he had been driven around all day to collect stories from the families of war dead:9

When the public announcements of the war dead came in, you got in a car with a list of addresses and rushed to the family’s home. I spent whole days in that car visiting families. You assumed that they knew, but often they hadn’t heard anything. They’d wail and cry. It was awful. There was a small placard at the entrance of each house where someone had died that said, “House of Honor.” Some houses had three of them out front. Our going there meant that a fourth member of that family had just been killed. Before the Pacific War broke out, the casualty reports weren’t piling up yet, so we’d always go out and try to get the story on each one. We’d get a photo of the dead soldier and we’d get a family member to talk about him. Usually we’d submit a story filled with fixed phrases like “They spoke without shedding a tear,” no matter how much they’d cried.

More than two million Japanese soldiers fell during the 1930s and 1940s. Their flags and senninbari were unable to protect them and they never returned home. During the past few decades however, an increasing number of the yosegaki hinomaru stripped from their dead bodies have been returning in their stead.

Many soldiers who took the flags back home as mementos started to feel regret, and have since approached news media, Japanese consulates and embassies, historians, volunteers and others to help them find the families of the fallen soldier they had taken the flag from. Often, families of allied soldiers found such a flag in their possessions after they died, and did the same.

Not all bereaved families are open to this. Nor are they willing or able to re-experience the pain. But most are—they are deeply moved when the flag is returned to them. As in many cases no mortal remains were ever repatriated to Japan, the returned flags represent a sort of homecoming for the fallen soldiers. Even almost eight decades after the end of WWII that still has deep meaning to the surviving family members, no matter how many generations removed.

The U.S. based Obon Society specializes in locating families of fallen Japanese soldiers. Their YouTube channel features countless touching video clips of families receiving a yosegaki hinomaru.

U.S. military forces also occasionally assist in getting a flag back to the Japanese family, as this photo released by the U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command shows.

The humanity of the return of these flags underscores their hidden message. Military propaganda promoted the practice of senninbari and yosegaki hinomaru. But the essence of the prayers embedded in senninbari and yosegaki hinomaru was to avoid bullets and return alive, rather than being powerful and successful on the battlefield, and killing many enemies.10

In a manner, this custom allowed people to express a wish for peace and avoidance of conscription that during a time of totalitarian militarism could not be expressed openly in any other way.

Today

The official send-offs, and the yosegaki, still exist in today’s Japan. But these days they are mainly employed as pep rallies for athletes, or farewell parties of graduates, exchange students, employees transferring to another offices, and retirees. Instead of the Hinomaru flag, usually a shikishi (色紙), a special large-sized square card used for writing poems, collecting signatures of famous people, and drawing illustrations, is used.

Yosegaki are especially popular amongst young people. For example, students will give one to their professor at the end of their course. Many Japanese craft stores sell cute stickers to illustrate the signed shikishi, and there are lots of samples online. The site yosegaki-free.com shares samples, ideas and templates.

The World

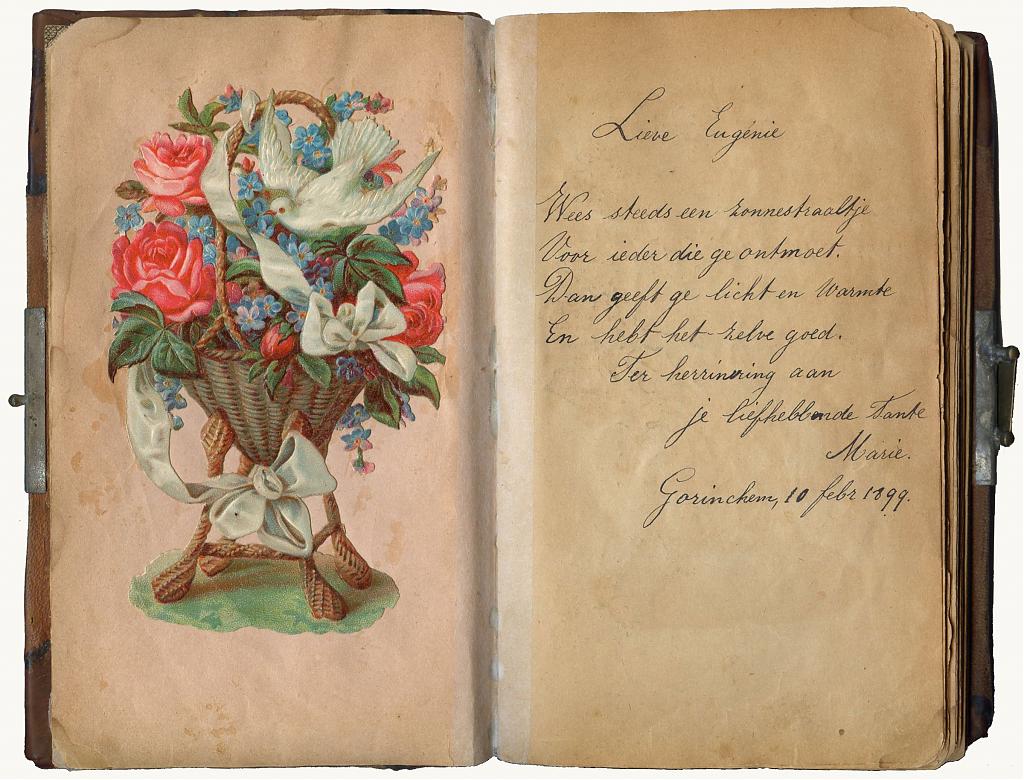

This custom is not unique to Japan. Other cultures have, or had, similar customs for commemorating friendships and connections. The album amicorum (book of friends) was popular in Dutch and Germanic cultures from the mid-16th century.

The custom was transferred to the United States in the late 18th century. These were mostly replaced by school yearbooks by the early 20th century. Usually, handwritten personal messages aimed at the recipient are written on one of the inner cover pages of these professionally printed books.

Because of rising costs, and student populations too large to introduce in a single book, increasingly fewer yearbooks have been printed in the U.S. since the 1960s and 1970s. During the past decades, many schools have dropped yearbooks in favor of social media alternatives. According to the only study done on the subject, the number of U.S. college yearbooks dropped from about 2,400 to 1,000 between 1995 and 2013.11

However, in academia, a Festschrift, a book honoring a respected person, is still commonly used. Guestbooks, visitors’ books at private homes, and books of condolence—all still widely used—are another form of this practice.

The Netherlands especially has a rich culture of books to capture messages from friends. Dutch girls between four and twelve years old used to own a poesiealbum (poetry album) in which their friends wrote illustrated poems and rhymes. They were still popular in the second half of the 20th century, but have since undergone a sustained decline.

Today they have mostly been replaced by vriendenboeken (book of friends), which are for any age and gender. These can be professionally printed through internet services like vriendenboeken.nl.

Notes

1 Cook, Haruko Taya, Cook, Theodore F. (1992). Japan at War: An Oral History. New York: The New Press, 121.

2 ibid, 122.

3 ibid, 123.

4 ibid, 124.

5 昭和館 帰還への想い ~銃後の願いと千人針~ 平成24年 Retrieved 2022-06-15.

6 Porter, Edgar A., Porter, Ran Ying (2017). Japanese Reflections on World War II and the American Occupation. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 39.

7 三浦和己・大傍正規(2016年)『 千人針 』( 1 9 3 7 年 ) の復元 ─ アナログ・デジタル技術を活用した二色式カラー映画の色再現。東京国立近代美術館〈東京国立近代美術館 研究紀要 20号〉Retrieved 2022-06-16.

8 Sledge, E.B. (2007). With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa. New York: Presidio Press, 70–71.

9 Cook, Haruko Taya, Cook, Theodore F. (1992). Japan at War: An Oral History. New York: The New Press, 214.

10 大江志乃夫(1981年) 『徴兵制』 岩波書店〈岩波新書〉、127頁。

11 Smith, Susan (2013). The Future of the Venerable Yearbook. cmreview.org. College Media Review. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

Bergland, Robert (2020). Research (Vol. 57): Social Media Use and Yearbooks. cmreview.org. College Media Review. Retrieved 2022-06-14.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 1930s: Off to War, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/899/1930s-war-japan-family-sending-soldiers-off-to-war-hinomaru-good-luck-flag

Glennis A Dolce

another wonderful post. the photographs… the faces. I did not know about senninbari at all but so very interesting. the videos too- i’d love to see that found film… Again- thank you!

#000736 ·

Tim Hornyak

Excellent article with some moving photos. Keep up the good work!

#000737 ·

Kjeld (Author)

@Glennis A Dolce: Thank you so much for the kind words. NHK did a documentary on the movie. I have tried to find it on YouTube, but no luck so far…

#000738 ·

Kjeld (Author)

@Tim Hornyak: Glad you liked it, Tim. Sometimes I am surprised about the images I find in my own collection! All of these work so well together to get this story across. And sometimes art tells a story better than a photograph. I especially like the ukiyoe from 1937 showing the two women doing senninbari. Purchased it specifically for this story, all the other images were already in my collection.

#000739 ·

glennis

Hi Kjeld-

I came back to this article to tell you I saw a senninbari here in LA at the Japanese American National Museum this past weekend! And thanks to you, I knew what it was! It’s an interesting one that was made in the Japanese concentration camps here for men being sent off to war to fight for the US in WW2. It has a lovely sumie painting depicting a tiger on it as well. Photos will be posted on my blog today. It was really great to see one in person. Hope all is well with you!

#000745 ·

Kjeld (Author)

@Glennis: How cool! I didn’t realize these were also made in the U.S. Interesting.

I just had a look at the photo of the senninbari on your blog. It is a beauty.

#000746 ·