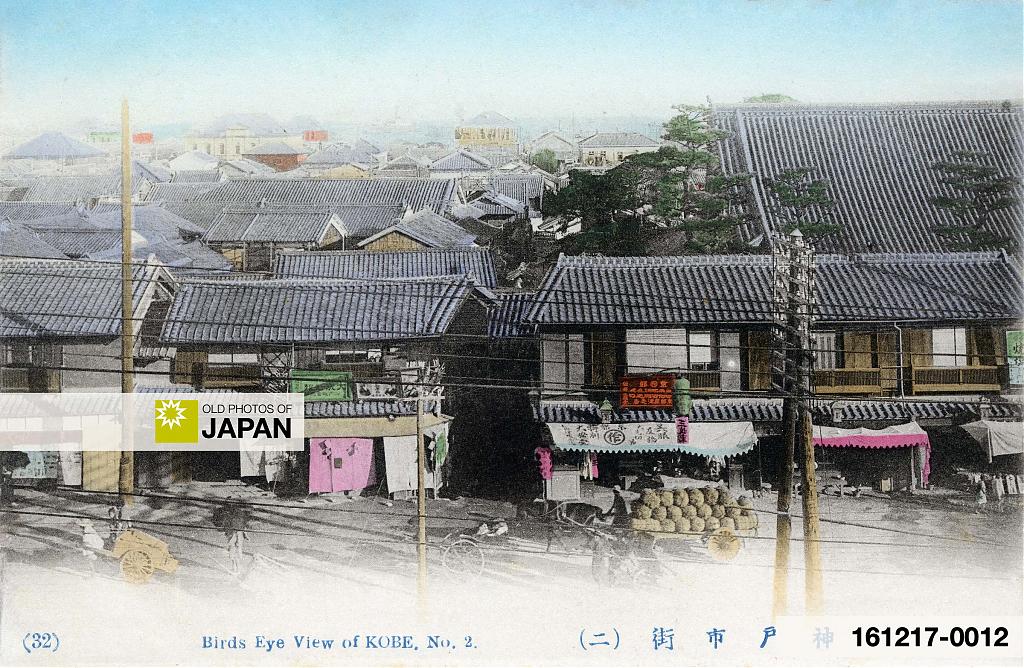

If you have been to Kobe, you have almost certainly walked down the long covered shopping arcade of Motomachi, Kobe’s most popular shopping street. This is what that street looked like in 1871 (Meiji 4).

You may have seen this photograph before as it is occasionally presented in history books of Kobe and Motomachi. In that case you will be amazed by the incredible sharpness and clarity of this print. In my extensive research I have not yet encountered a print even remotely approaching the quality of this one.

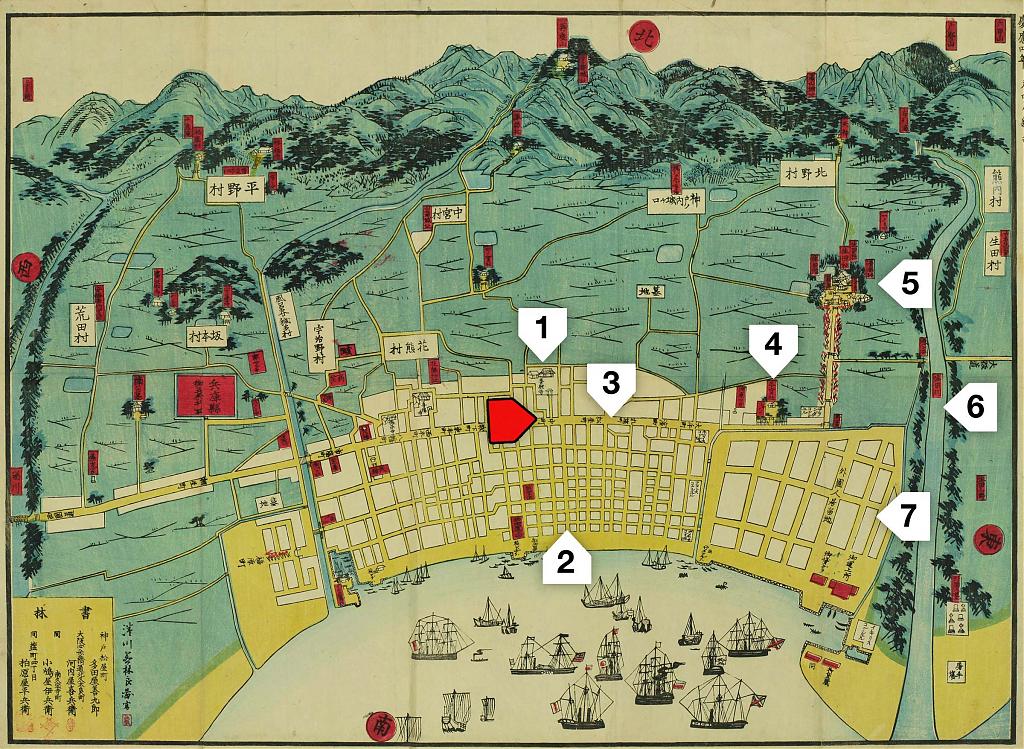

This particular spot was known as Nakamachi (中町). It is now Motomachi 3-chōme (元町三丁目), relatively close to present-day Motomachi Station. The photographer had the mountains on his left and the sea on his right.

This yet unknown photographer will not have imagined that he could hardly have chosen a better spot in Kobe. It has become home to a surprising amount of history.

Saigoku Kaidō

At the time this scene was photographed, the road was still known as the Saigoku Kaidō (西国街道), the important highway that connected Kyoto with Shimonoseki at the western end of Honshu. It was also known as the Sanyodō (山陽道). The road was renamed Motomachi-dōri (元町通) in 1874 (Meiji 7).1

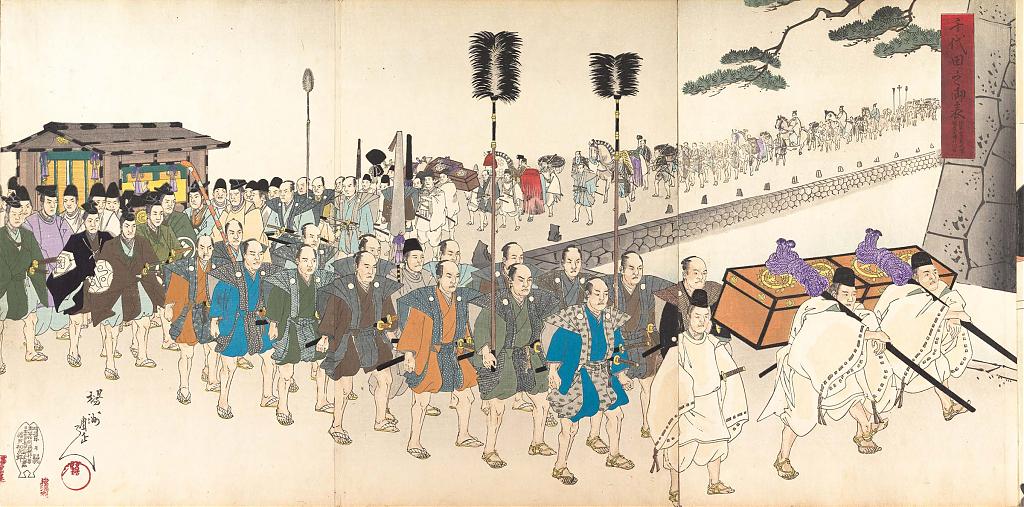

During the Edo Period (1603–1868), this was a lively highway used by traveling salespeople, pilgrims, and samurai. Daimyō (feudal lords) passed through with their long processions on their way to and from Edo (present-day Tokyo) for their alternate-year residence there. This system was known as sankin-kōtai (参勤交代).

Even though it was the main road, it was just a few meters wide. During the Meiji period (1868–1912) it turned into a crowded shopping street, so it was widened In 1892 (Meiji 25).

Zenshōji

The building with the fire lookout tower is the Kobe town hall (神戸町会所), formerly the Kobe Village Assembly (旧神戸村の村会所).2

According to the contemporary newspaper Kobe Chronicle, Japanese politician and statesman Hirobumi Itō (伊藤 博文, 1841–1909), who was Hyogo Governor between July 12, 1868 and May 21, 1869, often visited here when it was temporarily used as the foreign affairs office of the newly established Meiji Government (維新政府の外国事務局).

Near the building with the tower was an entrance way to Zenshōji (善照寺), then an important temple in Kobe. It was located on the left of the houses in the front. The approximate current address of where the temple stood is 3-13 Motomachi (神戸元町3丁目13).

Zenshōji was one of a cluster of four temples, and a shrine, on this Kobe stretch of the Saigoku Kaidō. The other four were Zenpukuji (善福寺) in 6-chōme, and Gokurakuji (極楽寺), Hachimandera (八幡寺), and Tenjinsha shrine (天神社) in 5-chōme.

Zenshōji is said to have been founded in 1585, and belongs to the Jōdo Shinshū school of Buddhism. It has played a significant role in Kobe’s history.

A Temple of Importance

My research strongly suggests that between January and April 1868 (Keiō 4), Zenshōji housed the very first consulate of the Netherlands in Kobe.3 Kobe had just been opened to foreign trade on January 1 of that year and no foreign buildings had yet been built.

The consul was Albertus Johannes Bauduin (1829-1890), chief agent of the Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij (Netherlands Trading Society). This Dutch trading company had been established by King William I of the Netherlands in 1824.

This is a new finding, first published here. I contacted the current priest of Zenshōji, as well as Kobe University, Kobe University Library, and Kobe City Museum, but this information was completely unknown. I could also not find any information about this in any book that I consulted.

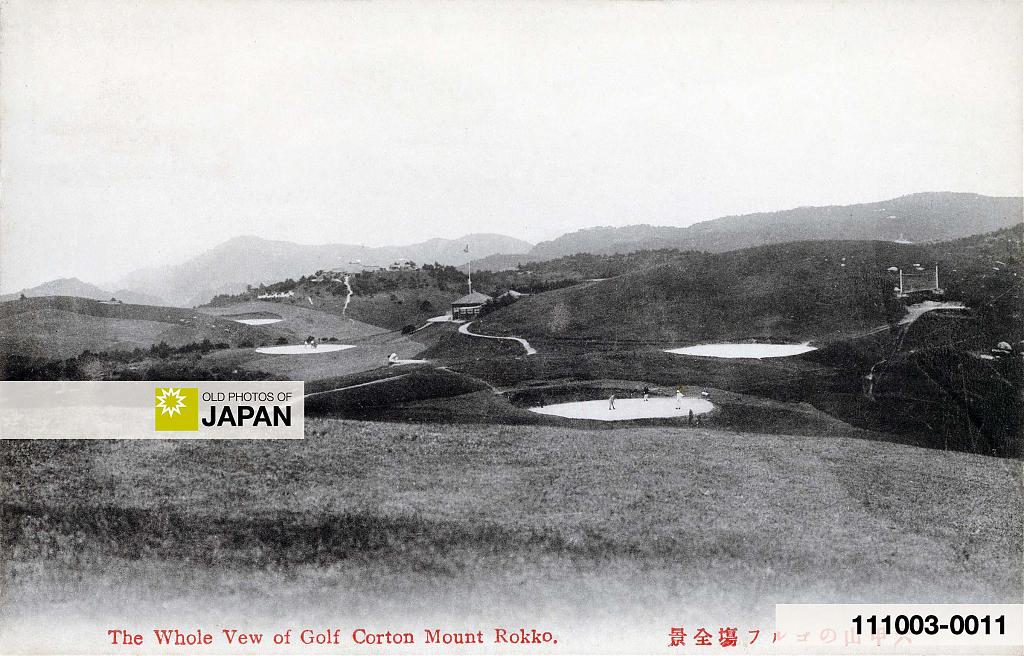

Celebrated longtime Kobe resident Arthur Hesketh Groom (1846–1918), who built Japan’s first golf course and founded the country’s first golf club, also lived at this temple for a brief period after his arrival in April 1868.4

Zenshōji chief priest Sazumi Sasaki (佐々木先住) encouraged Groom when he became homesick and introduced him to his future wife Nao Miyazaki (宮崎直), a daughter of a samurai family.4 The couple had 15 children and were reportedly extremely close. Sadly, six of their children died prematurely.

Education

Zenshōji left a surprisingly important imprint on the educational history of Kobe.

In 1873 (Meiji 6), Kobe’s first elementary school (一番組小学校) was launched in the main hall of Zenshōji after the promulgation of Japan’s new Fundamental Code of Education (学制) the previous year. In 1874, this school moved into the building with the fire lookout tower (the name was changed to 神東小学校).1

Zenshōji is also where in 1887 (Meiji 20), Kobe Shinwa women’s university (親和学園) was launched, as Shinwa Girls’ School (親和女学校), by head priest Yūsei Sasaki (佐々木祐誓).5

Unfortunately, this historical temple was destroyed in an air raid in 1945 (Showa 20). It is now located in a modern concrete building at Yamamoto-dori (山本通 5-9-5), but is still run by a member of the Sasaki family.

Postcards

Amazingly, the historical significance of this little corner of Kobe continues.

The postcard above shows approximately the same spot as the top photograph, as it looked around 1908 (Meiji 41), almost four decades later. It is photographed from the same direction, albeit from street level.

On the left, you can see the postcard store of Sakaeya Shoten (栄屋商店). Sakaeya was founded in May 1893 (Meiji 26) by Kōtarō Imaki (今城高太郎), born in Toyoura-gun in Yamaguchi Prefecture, as a shop selling ryū kitte stamps (竜切手).6

Ryū kitte were extremely popular with foreign collectors and were exported worldwide. Sakaeya was therefore perfectly located on Motomachi-dōri. It had already become Kobe’s main shopping street, and it was within walking distance of the foreign settlement.

Besides stamps, the company also sold imported playing cards and framed paintings, as well as other imported goods.6 This later turned out to be pivotal to Sakaeya becoming an extremely successful publisher of postcards.

First cards

Sakaeya first started selling postcards some time after the closing of the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 (Meiji 27-28),6 probably in the late 1890s (early Meiji 30s).7 This makes it, together with Yokohama based Ueda (also Uyeda), one of the first postcard publishers (絵葉書屋, ehagakiya) in Japan. This was at a time when the word ehagaki (picture postcard) didn’t even exist yet.

It appears that the postcard business was not very profitable and soon sales were stopped. Sakaeya was many years ahead of its time.

The time was finally ripe for postcards when the Russo-Japanese War broke out in 1904 (Meiji 37). The war created an enormous postcard boom in Japan, which lasted from 1904 (Meiji 37) through at least 1907 (Meiji 40). In 1890, some 96,430,610 postcards were sold in Japan, by 1913 this had risen to 1,504,860,312. Only in Germany more postcards were sold.8

By sheer coincidence, at around the start of the conflict some 200 postcards of flowers were mixed in with a foreign shipment that arrived at Sakaeya. Imaki had not ordered them, but decided to put them out in his store anyway. They sold as hot cakes. Good businessman that he was, Imaki immediately realized the opportunity and decided to go into the postcard business. Sakaeya became both a publisher and wholesaler of postcards.6

Success

The company was clearly good at what it did. During a 1906 (Meiji 39) postcard exhibition in nearby Osaka organized by Osaka Minatsukikai, the company won an award for a series of 8 postcards entitled “Kobe yori Akashi,” showing the area between Kobe and Akashi as it appeared 200 years earlier.6

The success of the postcard business inspired Imaki to begin producing postcard and photo albums. He also appears to have sold a large number of photographs of famous Japanese movie actors and actresses.6 These kind of photos are called bromides in Japan, not to be confused with the bromide photo process.

Imaki’s success was not limited to his business. He and his wife were the proud parents of ten children, seven sons and three daughters. Each of them seems to have inherited their father’s acumen. One son for example studied at Tokyo’s famous Waseda University, while another started working with the highly respected Daimaru Department Store chain.9 Imaki’s ability to give his children a good education is proof of the enormous financial success he must have enjoyed.

This success however, did not seem to go to his head. He was known as a quiet man who said little and enjoyed reading.6

In the 1940’s, Sakaeya sold mainly bromides, and imon hagaki (慰問葉書), sympathy cards that girls and young women sent to soldiers at the front. Unfortunately, the Second World War spelled the end of Sakaeya’s postcard business. The shop was burned to the ground in 1945 (Showa 20) during a firebombing air-raid by US planes. After the end of the war, the family did not return to the postcard business.8

About Sakaeya Cards

Marked Sakaeya cards are easy to recognize because of the distinctive Lion Mark on the lower right corner on the front of the card. It begins to appear around 1911 (Meiji 44). By this time the shop was famous and Sakaeya’s name had become representative for Kobe postcards. It sold many cards with images of buildings and locations in Kobe and surroundings, which even today show up at auctions and postcard fairs in large numbers.

Hand-tinted Sakaeya cards are usually numbered with a letter preceding the number, both enclosed in parentheses: (k111). They have no Sakaeya markings on the back.

There are also cards with the lion mark where the letter-number code is not enclosed in parentheses: k111. These cards usually have an Ueda back (see below). Ueda appears to have published a very large number of Kobe cards, usually without the lion mark.

Later cards with the lion mark are black and white. The mark is not on the front, but in the spot for the postage stamp on the back. The Sakaeya name is printed on the far left edge. Often a dove mark of Wakayama based postcard publisher Taisho (Hatto) is printed above the dividing line (see below).

Sakaeya was not the only Kobe based publisher of postcards, Another postcard publisher in Kobe was T. Takagi. This company printed its name on the back of the card, making it easy to distinguish the company’s cards from Sakaeya cards.

Motomachi-dōri Today

Motomachi-dōri is still a popular shopping street today. Since 1953 (Showa 28), it has become a covered arcade.1 This has greatly increased the number of shoppers, as they are no longer exposed to the extremes of weather.

Acknowledgements

The section about Sakaeya was written together with Yujiro Yasui (安井裕二郎). It is an edited version of a previously published article.

Notes

Notice that postcard #80201-0015 (Sakaeya) is photographed in the same decade as postcard #161217-0012 (bird’s-eye view on Motomachi), so you can see the same general area from both sides as it looked in the 1900s.

1 元町マガジン・昔の元町通・第4話 学校編(4). Retrieved on 2022-03-16.

2 (2008)識る力神戸元町通で読む70章 : 新しい日本の歴史認識1850-1955。日本の近代を語る会編、25.

3 These findings are based on a letter by Political Agent and Consul-General Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek, entries in an unpublished diary of Chancellor Leonardus Theodorus Kleintjes, a hand drawn map in the National Archives at Washington, and a document at Kobe University Library.

De Graeff van Polsbroek writes in Januari 1868 that the Dutch Consul had been assigned a “very good temple”: “Aan den Consul der Nederlanden te Hiogo werd op mijn verzoek een zeer goede tempel ter bewoning afgestaan en aldaar onmiddellijk de Nederlandsche vlag geheschen.” He does not mention the name of the temple, but “very good” limits it to just a few. Nationaal Archief, Netherlands, 2.05.01 Inventaris van het archief van het Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken, 1813-1870, 3147 1868-1870, 0080, January 6, 1868, De Graeff van Polsbroek at Hyogo.

On February 20, 1868, Chancellor Kleintjes writes in his diary that he moved in with Kobe Consul Bauduin. He reports on March 12 that he arrives at the “Dsjendsjoodsjie” temple, the Zenshōji (善照寺), in Kobe, after his return there from a one week stay in Osaka. On his return he was met bij Bauduin when he was close to Kobe. The walks that Kleintjes describes in his diary are all feasible from Zenshōji, and repeatedly include Bauduin. Diary of the Dutch diplomat and commissionaire Leonardus Theodorus Kleintjes, 1867-1870, TY92058899, International Research Center for Japanese Studies.

A hand drawn map of Kobe dated February 1868 has “Dutch Consulate” written at the approximate location of Zenshōji. National Archives, Washington. Despatches from U.S. Ministers to Japan, 1855-1906 Item: Jan. 2, 1868 – Apr. 8, 1868, 127.

In the list of documents about the opening of Kobe Port at the Kobe University Library, there is a document dated March 11, Keio 4 (April 3, 1868) mentioning four Japanese individuals and the “Dutch Consul” at Zenshōji in Kobe in regards to a “lodging notification” (止宿届書). Kobe University Library, G2-0696 行政-願書・要望・請願伺届.

On page 5 of History of Kobe by Gertrude Gozad, published in The Japan Chronicle, Jubilee Number 1868-1918, it is mentioned that the French consulate was initially located at Ikuta shrine, ruling this location out as the “very good temple” used by the Netherlands. Interestingly, after moving out of Zenshōji, the Dutch consulate was located at Ikuta Baba, the approach to Ikuta shrine, between approximately April 1868 and May 1870 (own research).

4 「神戸歴史トリップ」道谷 卓 著。中央区のあゆみ史跡・町名編「善照寺 山本通 5 丁目」Retrieved on 2022-03-16.

5 学校法人親和学園創立130周年記念サイト「歴史・沿革」Retrieved on 2022-03-16.

6 絵画絵葉書 類品付属品美術印刷製品仕入大観 (Kaiga ehagaki ruihin fuzokuhin bijutsu insatsu seihin shi ire taikan), published in 1925 (Taisho 14) by 大日本絵葉書月報社 (Dainihon Ehagaki Gepposha), Osaka.

7 The production and sale of postcards to which a stamp could be affixed was officially authorized by the Japanese government in October 1900 (Meiji 33).

8 Propaganda on the Picture Postcard, John Fraser, Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 3, No. 2, Propaganda (Oct., 1980), pp. 39-47.

9 Interviews.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Kobe 1871: Motomachi 3-Chōme, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 10, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/889/motomachi-3-chome

Jaroslaw

Hi, it is very interesting and valuable site. I am interested in Japanese postacrds and I am looking for confirmation for the mark you described as Taisho Hato. There are in my collection postacrds with standard Taisho Hato marks and that another mark. It is interesting because there were used another fonts. and they were published in the same period with different marks. It look like Taisho always use bird with description “Taisho” (for 1/2 divided back means from 1908 I have not got earlier Taisho’s postcards I supouse). BR, Jerry

#000771 ·

Kjeld (Author)

@Jaroslaw: Thank you for your kind words.

By the way, UCSB professor Peter Romaskiewicz has done a lot of research on Japanese postcard publishers. Are you familiar with his article Working Notes on Japanese Postcard Publishers?

#000772 ·