A Japanese farmer holds a kiseru (煙管). The tiny pipe offered only two to three puffs, yet it reigned for over three centuries. It was embraced by all classes of Japanese society, even crossing gender boundaries.

Smoking a kiseru pipe was actually so common for Japanese women that there is a seemingly limitless number of ukiyoe woodblock prints and photographs of the subject. The women portrayed in these images vary from courtesans to privileged women with servants—quite literally illustrating that tobacco was enjoyed by all classes. In Japan, even court ladies enjoyed their smoke.

In his 1888 history of tobacco in Japan, British diplomat and Japanologist Ernest Mason Satow emphasized that virtually all Japanese women smoked. He quoted an anonymous author who mockingly asserted that “women who do not smoke and priests who keep the prescribed rules of abstinence, are equally rare.”1

Japanese author and dictionary compiler Jukichi Inouye (井上十吉, 1862-1929) specifically mentions pipe smoking enjoyed by women in his book Home life in Tokyo, published in 1910 (Meiji 43):2

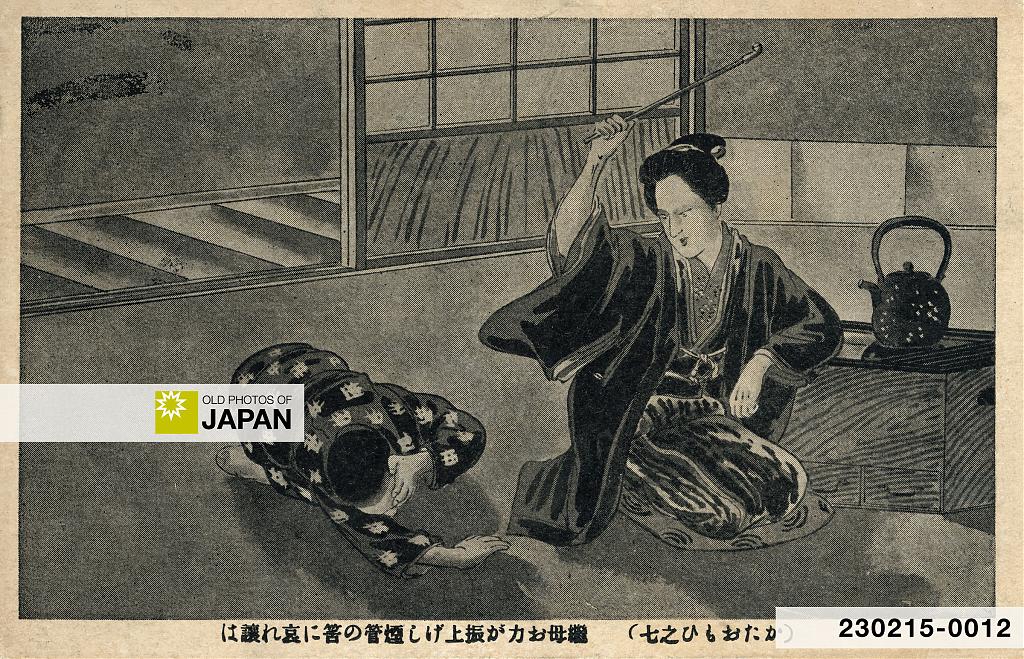

The wife who has been getting the children ready for school and helping her husband to dress, has now a little respite, during which she may glance through the papers and take a few whiffs of tobacco. Smoking is a general custom among Japanese women; but tobacco is smoked in homœopathic doses in tiny bowls. The Japanese pipe consists of a bowl, about a quarter of an inch in diameter and depth, bent into a tube, and a mouthpiece, both of metal, which are connected by a bamboo stem. The metal is brass for common pipes, while better sorts are of nickel, silver, or gold. The bamboo stem is five or six inches [13–15 cm] between the metal ends for pipes which are taken abroad, and not unfrequently a foot [30 cm] or more for those used at home. Among the lower classes the wife uses the long-stemmed pipe to emphasise [sic] her speech by beating the mat with it when she gives a piece of her mind to her truant husband; and a blow with it is pretty painful, as many an idle apprentice knows to his cost.

The kiseru appears to have been used a lot to get across an important point. British Japanologist Basil Hall Chamberlain mentioned this too in his one-volume encyclopedia Things Japanese, first published in 1890 (Meiji 23).3

Must it be revealed, in conclusion, that in vulgar circles the pipe, besides its legitimate use, occasionally serves as a domestic rod? The child, or possibly the daughter-in-law, who has given cause for anger to that redoubtable empress, the Obāsan, or “Granny,” before whom the whole household trembles, may receive a severe blow from the metal-tipped pipe, or even a whole volley of blows, after which the old lady resumes her smoke.

Kiseru Basics

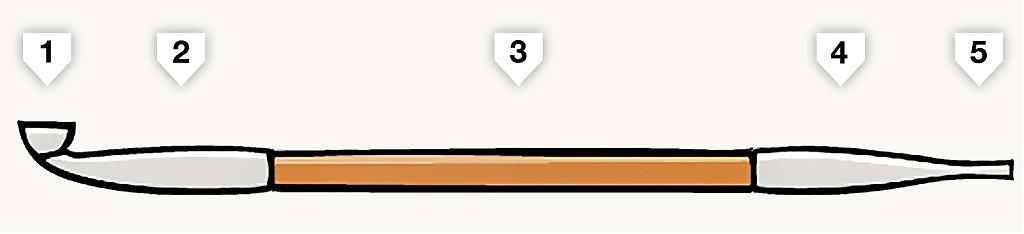

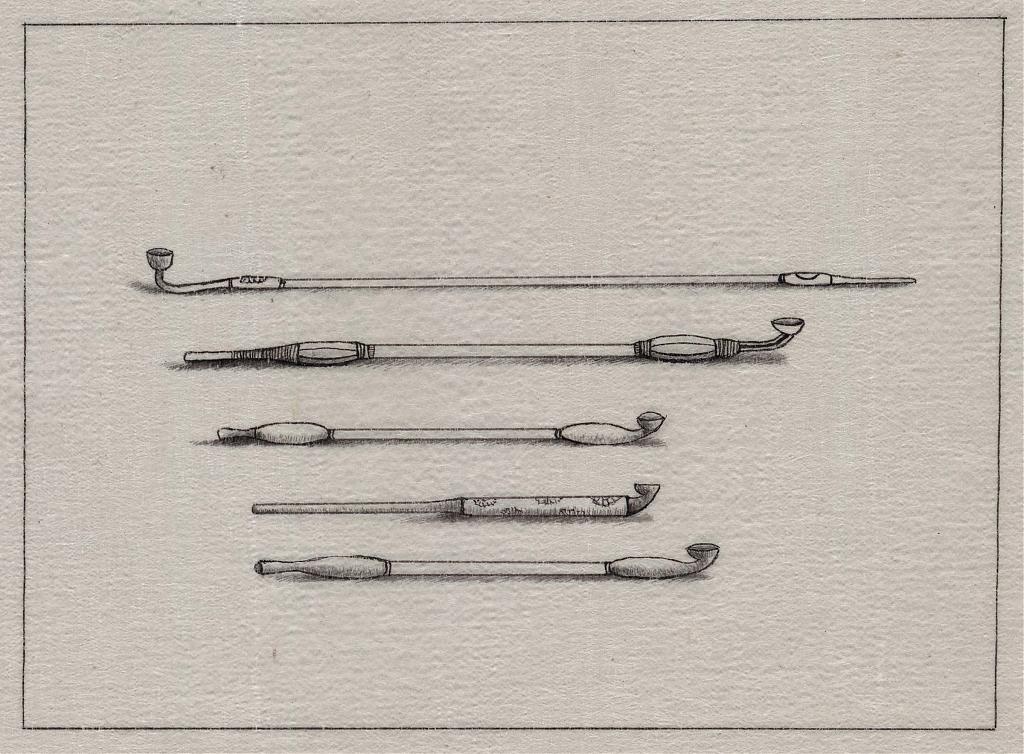

As explained above by Inouye, the most common kiseru consisted of three parts:

- a stummel (雁首, gankubi — 2 in the illustration below) featuring a tiny bowl (火皿, hizara — 1),

- a stem (羅宇, rau — 3), and

- a mouthpiece (吸口, suikuchi — 4).

The stem was generally made of wood or bamboo, the stummel and mouthpiece of iron, silver, or bronze. Artisans often adorned the latter two with intricate designs, transforming the pipes into works of art.

The length of the stem generally varied between 18 and 30 centimeters. Some were longer—the eccentric lord Tokugawa Muneharu (徳川宗春, 1696–1764) had a pipe that was 3.6 meters long.

A second less common type of kiseru was made of a single piece of metal.

Kiseru were carried in a case known as a kiseruzutsu (煙管筒). This was made of materials like lacquerware, leather, wood, bamboo, straw, ivory, stag antler, and even cloisonné.4 A small elegant tobacco pouch (煙草入れ, tabako-ire) held the tobacco.

The tabako-ire was connected to the kiseruzutsu by a short cord attached to a beautifully carved netsuke (根付). The latter was used to hang the tobacco set from the wearer’s obi as traditional Japanese clothing did not have pockets.

Many women carried their tobacco pouches in their sleeves, while they stuck their pipes in their obi, or even in the back of their hair.5

A large variety of crafts and arts came together in the creation of a kiseru smoking kit: lacquerwork, metalwork, horn and ivory carving, leatherwork, woodwork, and more. Each kit was a fusion of traditional Japanese crafts. Although they were objects of utility, many kits were in effect pieces of art that expressed the owner’s sensibilities and interests.

Tobako-bon

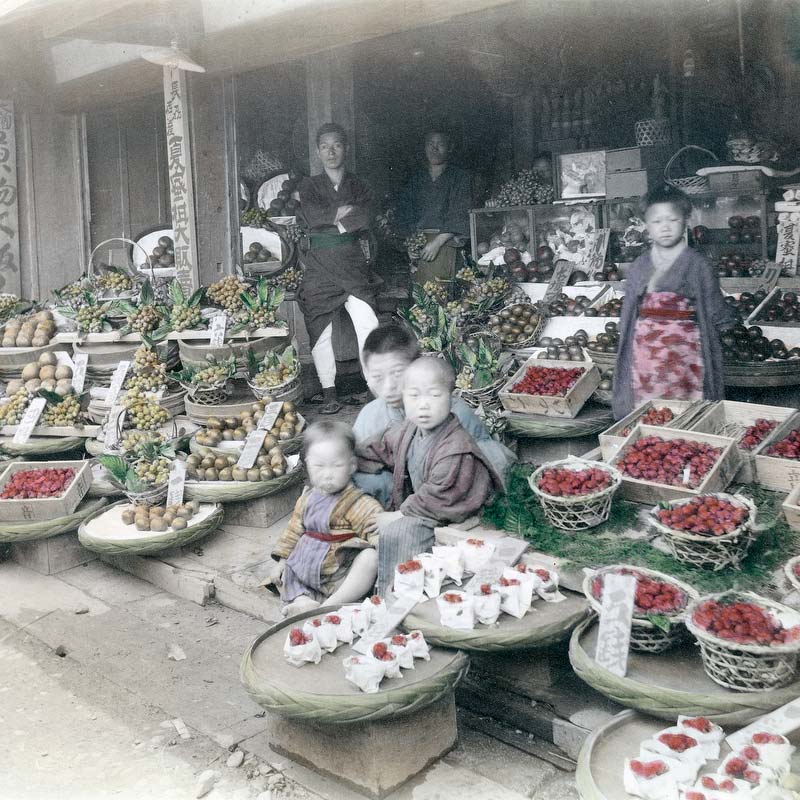

Another important implement of Japan’s smoking culture was the tobako-bon (煙草盆, tobacco tray). It was a basic necessity for every house, shop, office, tea house, restaurant, inn, and brothel:6

When any one enters a house, the first attention shown him by the female servants, after the customary greeting, is to set the tobacco-tray (Tabako-bon) before him, even before offering him tea.

Tobako-bon were generally fitted with a ceramic or metal container holding burning charcoal (火入れ, hi-ire), and an ashtray known as hai-otoshi (灰落し) or hai-fuki (灰吹き). The ashtray was generally made of bamboo, but other materials were used too.

The tobako-bon varied from simple wooden boxes to lavishly decorated lacquer boxes with drawers, sometimes referred to as tobako-dansu (煙草箪笥, tobacco chests). Often they featured hooks to rest the kiseru (きせる掛け, kiseru-kake).

During the 20th century, smoking shifted from kiseru to cigarettes, and tobako-bon mostly vanished. These days they are mainly used during the tea ceremony.

Thankfully, their previous importace has been preserved in countless ukiyoe woodblock prints and vintage photographs of Japan. Once you know what to look for, you will see them pop up again and again. As a test, try going back to the earlier photos in this article. Can you find all the tobako-bon?

Timing

The hai-otoshi (or hai-fuki) was an important part of smoking the kiseru. Using both well required a sharp sense of timing explained Japanologist Chamberlain.7

After the third whiff, the wee pellet of ignited tobacco becomes a fiery ball, loose, and ready to leap from the pipe at a breath; and wherever it falls, it pierces holes like a red-hot shot. But the expert Japanese smoker rarely thus disgraces himself. He at once empties the contents of the mouthpiece into a section of bamboo (hai-fuki), which is kept for the purpose, somewhat after the fashion of a spittoon. Not so the foreigner ambitious of Japonising himself. He begins his new smoking career by burning small round holes in everything near him,—the mats, the cushions, and especially his own clothes.

Kizami

The kiseru required a very special tobacco known as kizami tabako (刻み煙草). It was cut so finely that it resembled coarse hair. No more than 0.2 grams of tobacco fit into the tiny bowl, making smoking a kiseru a laborious exercise.8 Unlike with other pipes, cigars, or cigarettes, one could not smoke while doing something else. In Japan, smoking truly was an activity of leisure:9

A small pinch of tobacco is put into the bowl, and two or three whiffs are all that can be got from it. A Japanese does not merely smoke, that is, get the smoke into his mouth only, but actually swallows it and then slowly emits it from his mouth or nostrils. Women generally emit it from their mouths only. The tobacco smoked is dried leaves cut into fine slices. The filling and emptying of the bowl takes about as much time as the smoking of it, so that one cannot smoke while doing something else; but it is an excellent time-killer, as day-labourers will testify.

This is Part 1 of a two-part series about the tobacco culture of old Japan. More coming soon!

Notes

The top photo might be by Shinichi Suzuki II (鈴木真一, 1855–1912).

1 Sato, Ernest M. The Introduction of Tobacco into Japan. Tokyo, Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan Vol. VI Part 1, 78.

2 Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 140.

3 Chamberlain, Basil Hall (1902). Things Japanese Being Notes on Various Subjects Connected with Japan for the Use of Travellers and Others. J. Murray: 370–371.

4 古美術緑青〈No.28〉October 1998. マリア書房, 51.

5 Stevens, Thomas (1888). Around the world on a bicycle. From Teheran to Yokohama. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searles, and Rivington, 455.

“Everybody in Japan smokes, both men and women. The universal pipe of the country is a small brass tube about six inches long, with the end turned up and widened to form the bowl. This bowl holds the merest pinch of tobacco; a couple of whiffs, a smart rap on the edge of the brazier to knock out the residue, and the pipe is filled again and again, until the smoker feels satisfied. The girls that wait on one at the yadoyas and tea-houses carry their tobacco in the capacious sleeve-pockets of their dress, and their pipes sometimes thrust in the sash or girdle, and sometimes stuck in the back of the hair.”

6 Rein, J. J. (1889). The industries of Japan, together with an account of its agriculture, forestry, arts, and commerce: from travels and researches undertaken at the cost of the Prussian government. London : Hodder and Stoughton, 132.

7 Chamberlain, Basil Hall (1902). Things Japanese Being Notes on Various Subjects Connected with Japan for the Use of Travellers and Others. J. Murray: 369.

8 古美術緑青〈No.28〉October 1998. マリア書房, 51.

9 Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 140.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Studio 1880s: The Way of the Kiseru, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/880/japanese-tobacco-kiseru-pipe-meiji-19th-century-vintage-albumen-photo

Tim Shaw

Love this article, probably because I really enjoy Japanese design at the historical and domestic level.

#000752 ·

Kjeld (Author)

@Tim Shaw: Thank you, Tim. I love how beautiful design is integrated into all aspects of Japanese tobacco culture. Pipes, tobacco pouches and ashtrays may have been introduced from abroad, but the Japanese did something very special with what they were handed. It is amazingly elegant and unique.

#000753 ·