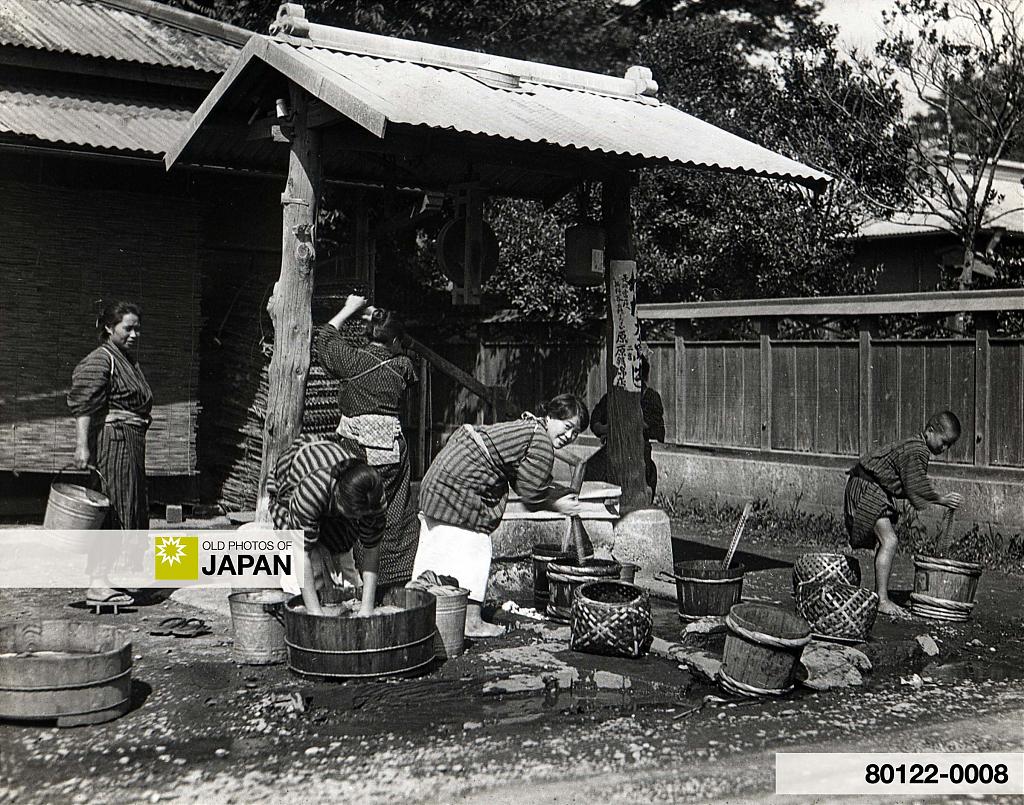

Three Japanese women in kimono are doing the laundry. The woman in front is washing clothes in a wooden tub, while the other two are spreading separated kimono on wooden boards. How do you wash a kimono?

Housewives in the past worked long days. They may have had domestic help, but all the work was done by hand, without electrical appliances. No electric washing machines, sewing machines, vacuum cleaners, refrigerators, blenders, and so on.

Housework was physically extremely demanding, and took loads of time. Doing the laundry especially so.

In her book A Rocking Chair for a Housewife, Japanese author Yoshiko Shigekane (重兼芳子, 1927–1993), recalled how much she hated doing the laundry when she was in her twenties, raising three children:1

Using this traditional method, I washed everything from children’s diapers to sheets, shirts to futon covers, for three to four hours a day. Every day. My husband wore kimono and tabi socks. When he came home, washing his tabi was such a pain. … My baby screamed on my back, and somewhere else in the house the other kids were fighting like devils. The mountain of soiled clothes never shrank, and I was mad as hell.

Later in the book, Shigekane writes that the arrival of the washing machine gave her “the strongest emotion I have felt in my whole life.”

The period that Shigekane describes was the fifties. At this time, relatively easy-to-wash Western clothes had already overtaken kimono. Japanese women had also started using soap and washing boards (洗濯板, sentaku ita), which became common in Japan from the Taisho period (1912–1926).2

Washing clothes—especially kimono—was even harder before the arrival of Western fashion, affordable soap, and washing boards.

Well-Side Council

In old Japan, washing was done at different locations. Some homes had their own well, but in towns there were usually communal wells, or a small waterway which ran through the street. In the countryside, washing was also done at a nearby river.

These places fostered community, but also became great sources of gossip. This survives in Japanese as the expression for idle chatter and gossip, idobata kaigi (井戸端会議), well-side council.

Step 1: Washing & Starching

Clothes were hand-washed in a wash tub known as a tarai (たらい). Women generally worked low to the ground and often sat on a box, or even a geta (wooden clog).

Instead of soap, which was a precious commodity, all kinds of other products were used. The most common were ashes (lye) and togijiru (米のとぎ汁, water that has been used to wash rice). Some women used the leaves of the pink silk tree (ねむの木の葉), the water used for cooking noodles, or yet something else. What detergent was used depended greatly on the geographic location.3

Because warm water removes dirt better, the tub with water was first placed in the sun for a while before washing.

After washing, the kimono was dipped in a natural starch. For material like light-colored cotton (淡色のもめん) and hemp (麻), rice starch (米糊, komenori) or wheat gluten (吟生麩, ginnamafu) was used. While funori (布海苔), made from seaweed, was used for dark-colored fabrics.

The starch protected the colors and made the fabric less prone to staining. Interestingly, funori is now used by conservators all over the world to restore and protect antique artworks.4

Step 2: Drying

After washing, kimono were dried in one of three ways: using bamboo poles, starch boards, or stretched and suspended like a hammock.

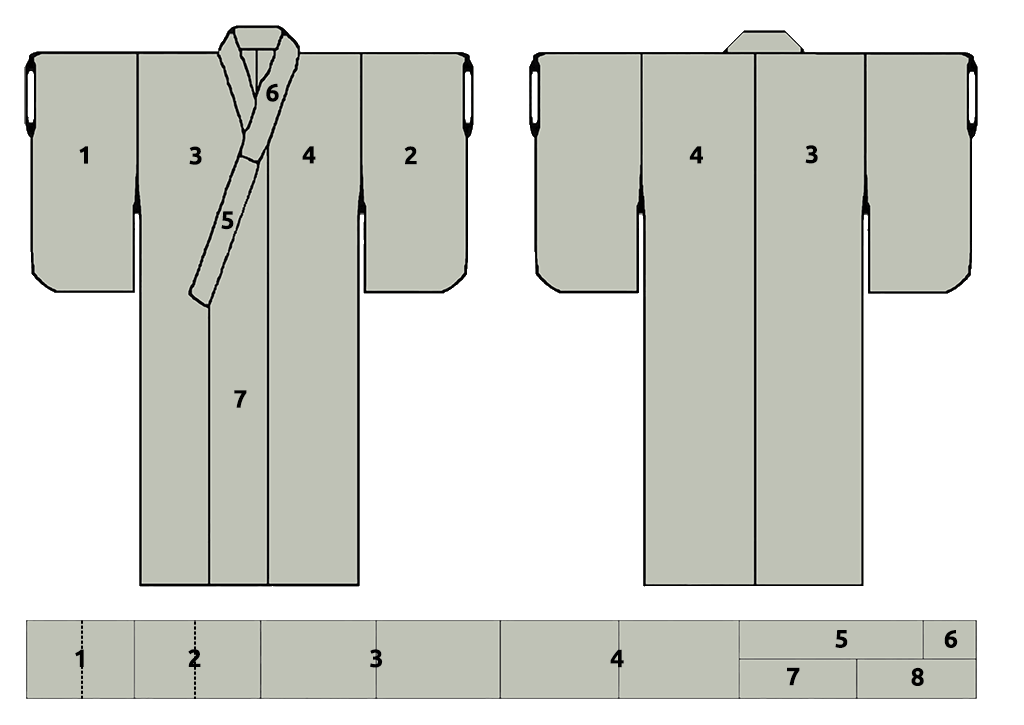

Non-delicates like a juban (undergarment) were slid over a bamboo pole. But delicate kimono were first dissembled. Kimono are generally made of eight rectangular strips cut from a single bolt of cloth, which are stitched together. Before washing, these stitches were removed.

The kimono were then stretched out to dry using one of two so-called araihari (洗い張り) methods.

The most common method was placing the cloth on a starching board (張り板, hari ita) made of cedar. By stretching out the cloth on the board, wrinkles were removed. This method was called itabari (板張り).

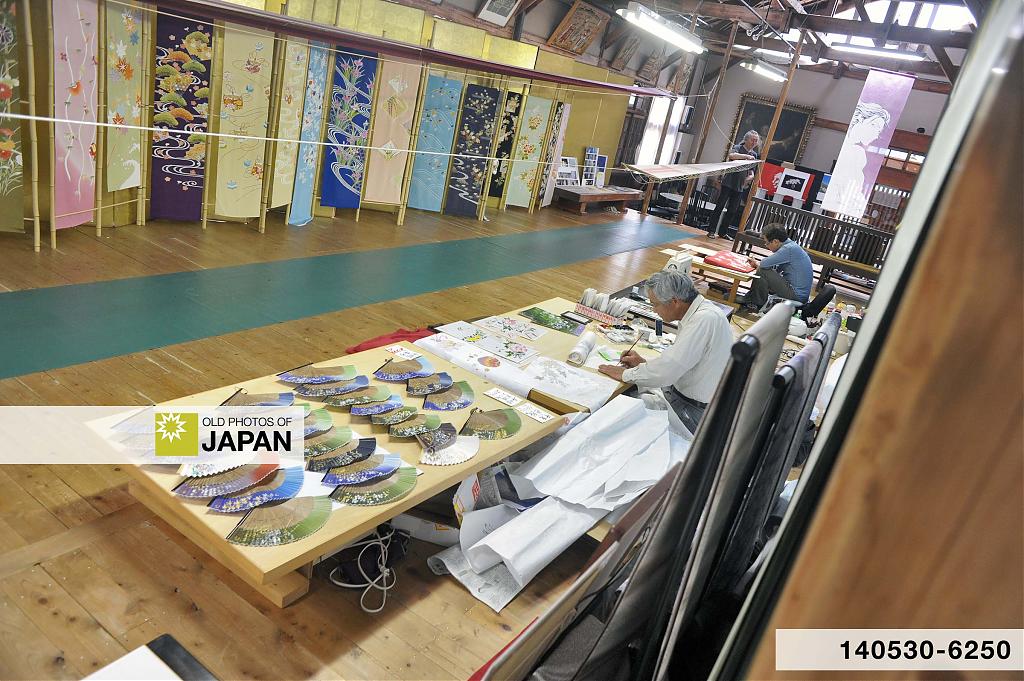

Another method was shinshibari (伸子張り). To stretch the fabric, bamboo sticks with sharp ends (伸子針, shinshibari) were inserted into the edge of the cloth, which was suspended in the air like a hammock. A hundred shinshibari could be used for a single kimono.

Incidentally, this is the same method used when kimono fabric is dyed. It can still be observed today at dyeing ateliers and workshops.

This rescue project is funded by readers like you

Old Photos of Japan provides thoroughly researched essays and rare images of daily life in old Japan free of charge and advertising. Most images have been acquired, scanned, and conserved to protect them for future generations.

I rely on readers like you to keep this project going.

Step 3: Repair and Reassembly

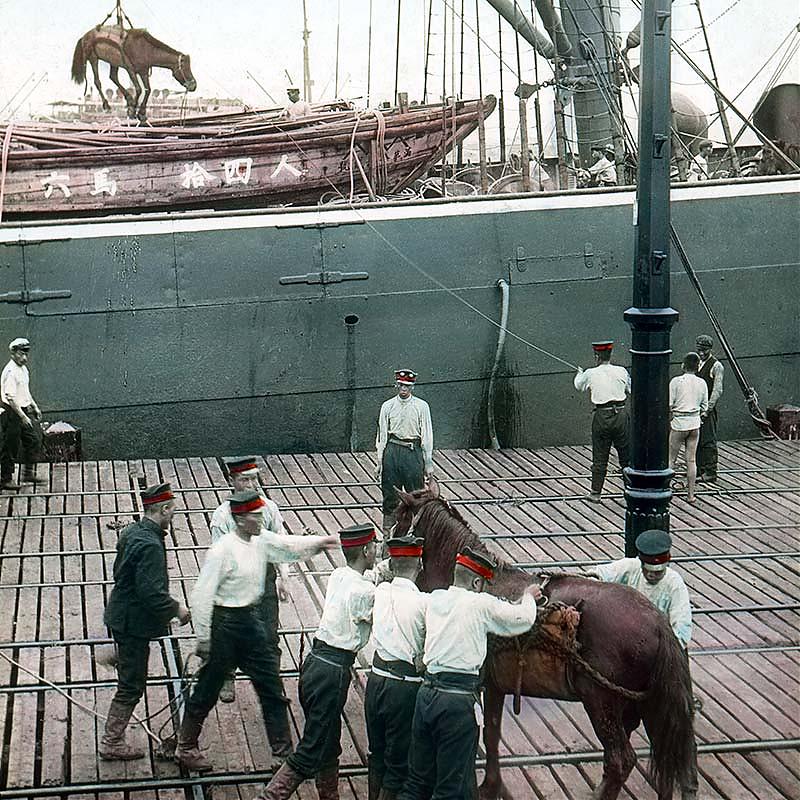

During this long laundering process, spots were removed, holes were repaired, and occasionally the complete bolt was re-dyed.

When the laundry was done, the kimono had to be reassembled. Housewives usually did this in the evening, after finishing all the other housework.

Sewing was just as demanding as the washing. There were single (単, hitoe), lined (袷, awase), and cotton-padded (綿入れ, wata-ire) kimono, as well as different types of kimono for men, women, and children. Each were cut and sewn differently. And all of this was done by hand.

Sewing was a basic necessity of life. If a woman could not sew, she could not marry. So, girls were taught by their mothers from a very young age to master this art. From the Meiji period (1868–1912) on, schools also started teaching sewing.

Naturally, some thread and pieces of fabric were discarded during this disassembly-repair-reassembly process. Women did not throw these out, but saved them up to make embroidered balls, called temari (手まり). Each thread and each color in the ball would recall memories of the life experienced while wearing the kimono.

In Home Life In Tokyo (191), Japanese author Jukichi Inouye gives a short summary of the washing duties at the start of the 20th century. He mentions that starching is done after drying, which seems a bit odd:5

There is always plenty of washing to do, especially in summer. If, moreover, there are young children in the family, the clothes they are constantly soiling have to be taken to pieces, washed, and remade. If the clothes are lined, wadded, or of the better quality of the unlined, they are taken to pieces and washed, and the pieces are then spread out on a smooth plank specially made for the purpose and laid out to dry in the sun. They are next starched, and when they are dry, they still adhere to the plank and so keep free from creases and shrinkages. The wadding is never washed. The underwear is also washed ; but unless it is of silk, it is not spread out. In summer the unlined clothes, called yukata or bath-dress, are washed every three or four days; and as every member of the family has two or more changes, there is always something to wash. The clothes and underwear which need not be spread out, are hung up on long poles which pass through the sleeves and are hoisted up on the pegs of two high upright posts. When dry, these clothes are spread out on a matting and starched and folded for use. Silks which require special skill in washing or have stains to be removed are sent to the dyer.

After all of the washing, repairing and re-assembling was done, the kimono could be folded and put away. Folding a kimono is an art in itself, almost resembling origami.

Foreigners were fascinated by the Japanese way of washing clothes. There is a staggering number of late 19th century souvenir photographs of Japanese women doing the laundry, especially photos featuring the starching boards.

By the 1960s, few Japanese women were still washing clothes as described in this article, and depicted on countless woodblock prints, souvenir photographs, postcards and documentary photos. These are now valuable documents of past, and mostly forgotten, customs.

Notes

1 重兼芳子『女房の揺り椅子』講談社、1984年「その伝統的な方法で、私は子供のおむつからシーツ、ワイシャツから布団カバーの類まで、毎日毎日三四時間かけて洗い続けた。亭主はウチに帰ると、着物を着て足袋をはくヒトだから、足袋の洗濯がもうたいへん。(中略)背中じゃ赤ん坊が泣きわめくし、向うではガキがけんかして瘤をつくる。汚れものの山は一向に減らないし、私はカッカッと頭にきてる。」「一生のうちで最も忘れられない感動。」

2 山口昌伴『水の道具誌』岩波新書、2006年、193頁

3 Shibusawa, Keizo (1958). Japanese culture in the Meiji era vol.5 (Life and culture). Tokyo: The Toyo Bunko, 46.

4 See a list of industry research on the use of funori on the site of the Canadian company TRI-Funori.

5 Inouye, Jukichi (1911). Home Life in Tokyo. The Tokyo Printing Company, Ltd., 142–144.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). 1900s: How do you Wash a Kimono?, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on February 12, 2026 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/877/laundry-washing-clothes-meiji-19th-century-vintage-albumen-prints

glennis

great set of photos and info on washing clothes in early Japan. I was not aware of the washing boards and starching.

#000711 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

@glennis: Glad that my article contained new information!

Although it is very posed, and shot in the studio with a model, I love the postcard with the washboard.

#000717 ·

Kristin Newton

I live by the Marukogawa river in Futakotamagawa. The lady across the street knows the history of the whole neighborhood and informed me that the original family who lived here were kimono dyers. They used to wash the kimono fabric in the Marukogawa. Now the river is a walled by concrete but when my neighbor was young it was a natural river which often overflowed its banks.

#000814 ·

Kjeld (Author)

@Kristin Newton: I love these little tidbits of historical memory. I hope a more beautiful and natural way against flooding can be found. Concrete is not very kind to the life that used to flourish in and around waterways…

#000815 ·