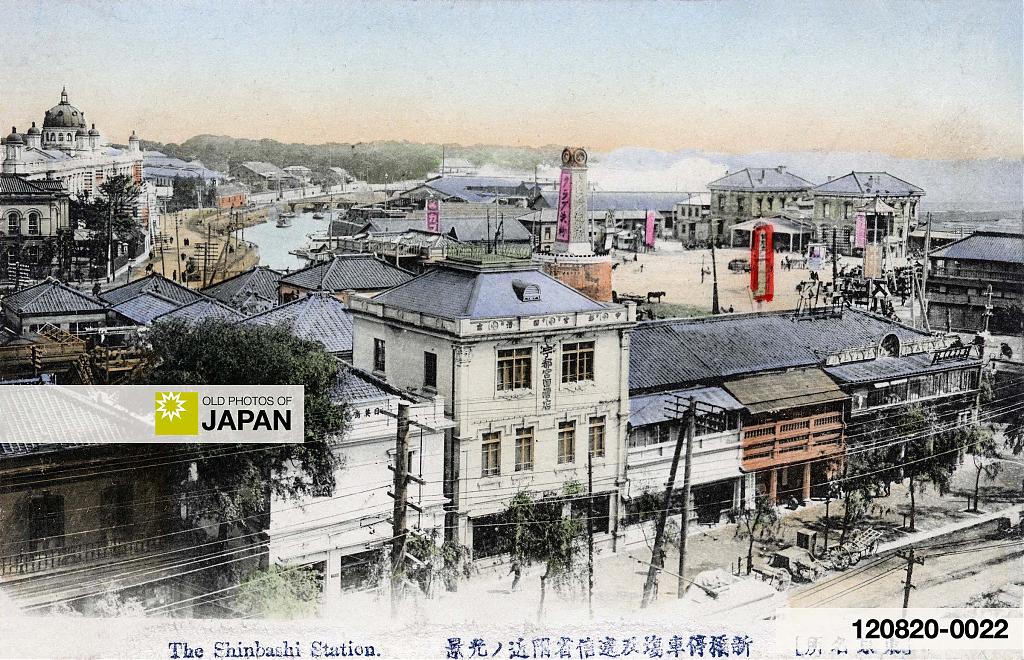

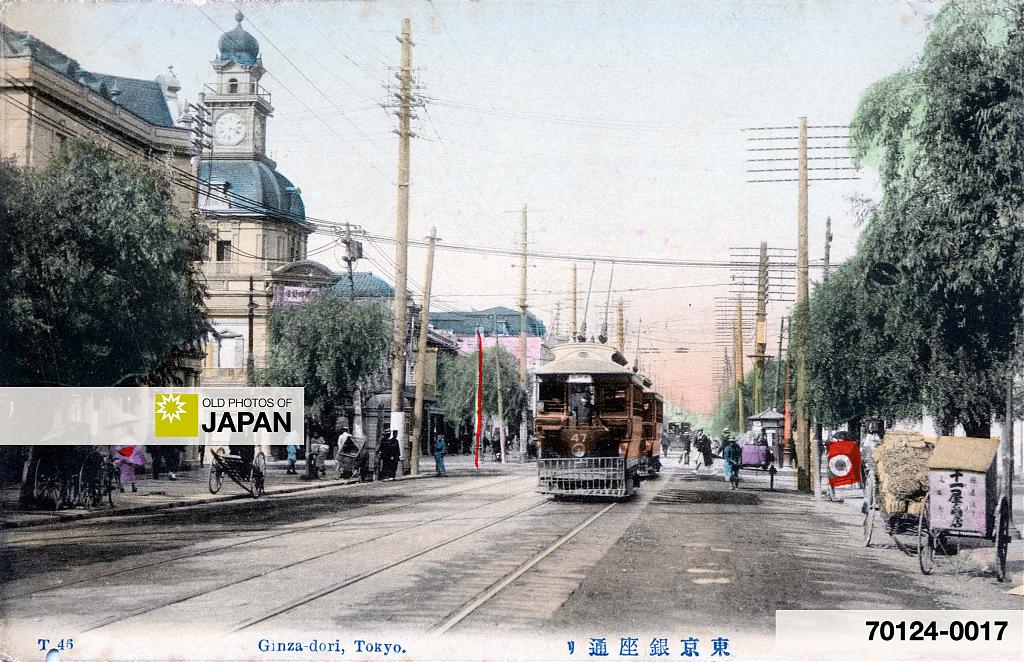

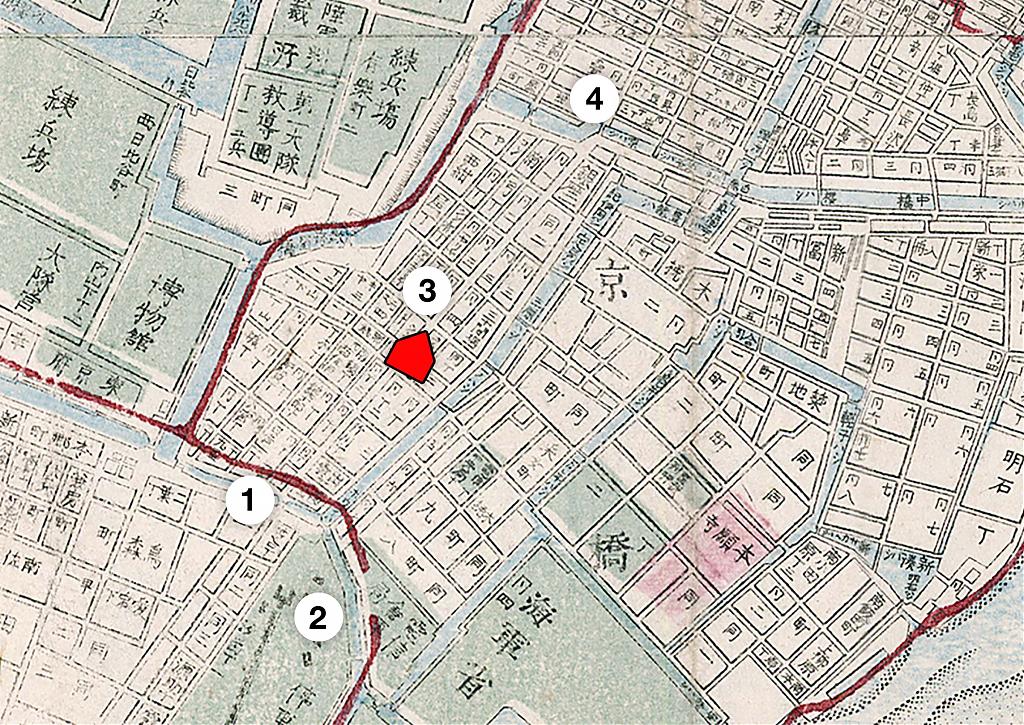

Rickshaws on Tokyo’s Ginza avenue in the late 1870s. This intersection, now the location of the luxurious Wako store, was the information center of the Japanese empire.

Have a careful look at this photo. The corner building on the left houses the offices of daily newspaper Choya Shimbun (朝野新聞). The pro-democratic anti-government newspaper was founded in 1874 (Meiji 7) and discontinued in 1893 (Meiji 26).

Across the street (on the right of this photo) are the offices of another daily, the Tokyo Akebono Shimbun (東京曙新聞). It was located here from December 1876 (Meiji 9) through March 1882 (Meiji 15).

During the Meiji Period, this intersection was actually crowded with newspaper and magazine publishers, printing houses and advertising firms. Around 1890 (Meiji 23), Ginza counted over a hundred newspaper offices.1 It was the information center of the Japanese empire.

As these newspapers slowly became more independent, they inspired the People’s Rights Movement (自由民権運動, Jiyū Minken Undō), and the formation of a modern civil society. It could be said that Japan’s modernization first started taking form from this spot at Ginza at the time that this photo was taken.

Ginza got its name after one of the Shogunate’s mints was moved here from Shizuoka in 1612. The mint was moved to Nihonbashi in 1800, but the name stuck.

The area was famous for its many artisans, but this changed after a devastating fire in 1872 (Meiji 5). To prevent a recurrence, the Japanese government decided to rebuild the area with fire-resistant Western style brick buildings and hired British architect Thomas James Waters to create a Brick Town.

Simultaneously, the street was widened to 27 meters, more than twice as wide as it used to be. It featured Japan’s very first sidewalks. The ambitious multi-year plan took until 1877 (Meiji 10) to fully complete.

The Georgian style brick houses with overhanging balconies look romantic on old photographs. But they were extremely unpopular. A report from 1872 stated that of the 324 planned buildings, future tenants had been secured for only 84.2

They were also badly built and totally unsuited to the humid Japanese climate. Damp and dark, quite a few remained vacant for a long time. Eventually, many buildings were rebuilt in more of a Japanese style. Buildings in the backstreets were completely Japanese or of a mixed style.

The buildings might have been unattractive, the area was not. In the same year that the fire destroyed Ginza, Shimbashi Station was built at its south-western end. It was the terminal station of Japan’s first Railway, connecting the international port of Yokohama with the capital. This effectively turned Ginza into Tokyo’s entry portal for all new things from abroad.

In addition to newspaper offices, it attracted countless entrepreneurs riding the wave of the national policy of Bunmei Kaika (文明開化, Civilization and Enlightenment), the effort to quickly modernize the country so it could compete with the West.

Over the next few decades, shops selling imports and new products opened up one after the other. There were western-style restaurants and bakeries, western-style furniture, bag and clothing shops, clock dealers, and so on. All these shops featured modern window displays and could be entered freely without customers needing to take off their shoes.

One of the first entrepreneurial enterprises to move here, already shortly after the fire, was Shiseido. It set up shop in Ginza as a Western style pharmacy that would turn into today’s multinational cosmetic company.

The new Ginza really came to life from the 1880s. In 1882, a horse-drawn streetcar service lead through Ginza to Nihonbashi. It was later extended to Asakusa. The same year electric street lights were installed.

World famous watchmaker Seiko, founded by Kintarō Hattori (服部金太郎, 1860–1934), was born at Ginza. In 1885 (Meiji 18), Hattori bought the offices of the above-mentioned Choya Shimbun and build a shop with an iconic clock tower. It became the symbol of Ginza. The famous Wako Building now stands at this location.

On July 4, 1889 (Meiji 22), Japan’s first beer hall, Ebisu beer hall, was opened near Shinbashi Bridge. In 1911 (Meiji 44), Café Printemps was started, fairly close to Ebisu. Coffee and alcohol was served by young attractive women. It became a popular spot for famous authors like Kafu Nagai and Ogai Mori, as well as geisha from nearby Shimbashi.

Soon, other cafés followed. Café Paulista, Café Lion, Tiger, and so on. The cafés and atmosphere made it popular for young people to wander around Ginza, an activity that became known as Gin-bura, a blend of Ginza and bura bura (strolling).

Ginza was once again devastated in 1923 (Taisho 12), when the Great Kanto Earthquake unleashed raging fires. But like the fire of 1872, this actually created new opportunities. Major department stores like Mitsukoshi, Matsuya and Matsuzakaya built gorgeous new branches, transforming the avenue into an elegant modern shopping street that could vie with counterparts in any Western capital.

Ginza now became the epicenter of modern life and represented Japan’s urban future. The very name symbolized a modern lifestyle. This was where the modern Japanese woman, known as moga (モガ, shortened from modern girl), went to be seen. They also found jobs here at its many cafés. Mobo (モボ, modern boys), dressed in the latest Western fashion, searched them out.

From the mid-1920s on, the name Ginza was increasingly used as the name of cafés, bars and other entertainment establishments all over Japan. Local entertainment districts in major towns were nicknamed Ginza. Like Niigata Ginza and Sapporo Ginza. Temporarily halted by the Asia–Pacific War, this trend was rekindled in the postwar years. By 1956, 487 shopping districts in Japan had added Ginza to their local name.3

These days, Tokyo doesn’t really have a single center anymore, and Ginza is no longer Tokyo’s main attraction. But if you would have asked a Japanese person during the first half of the 20th century where the center of Tokyo lay, they would have said it was the intersection at Ginza 4-chome.

It was born when the top photo was taken.

Japan Firsts at or near Ginza

| 1869 | Joint Stock Company (Maruzen) |

|---|---|

| 1870 | Rickshaw. Invented by Yosuke Izumi (和泉要助, 1829–1900) |

| 1872 | Western Pharmacy (Shiseido) |

| 1874 | Sidewalk Anpan |

| 1878 | Public stock exchange |

| 1882 | Electric street lamp |

| 1884 | Fountain Pen (Maruzen) |

| 1890 | Fruit Parlor (Sembikiya) |

| 1899 | Beer hall (Ebisu Beer Hall) Tonkatsu (fried pork cutlet) |

| 1900 | Public phone booth |

| 1901 | Typewriter company (Kurosawa Shoten Typewriter Manufacturing Company) |

| 1902 | Soda Fountain (Shiseido Pharmacy) |

| 1923 | Fruit punch (Sembikiya) |

| 1927 | Subway Line (Ginza Line between Asakusa and Ueno) |

| 1941 | Gunkanmaki sushi (銀座久兵衛, Ginza Kyubey) |

| 1946 | Sony |

| 1948 | Katsukarē (fried pork cutlet with rice and curry sauce) |

Notes

1 Tokyo Metropolitan Library. A Visit in the Great Edo. Emergence of western-looking streets. Retrieved on 2022/02/03. Seidensticker claims it was thirty: Seidensticker, Edward (1983). Low City, High City. Tokyo from Edo to the Earthquake. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 204.

2 Grunow , Tristan R. Meiji at 150 Visual Essays: Ginza Bricktown and the Myth of Meiji Modernization. Retrieved on 2022/02/03.

3 Young, Louise (2013). Beyond the Metropolis: Second Cities and Modern Life in Interwar Japan. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 193.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Tokyo 1870s: The Birth of Ginza, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on December 12, 2025 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/875/tokyo-ginza-4-chome-meiji

There are currently no comments on this article.