Houses, onsen ryokan (spa inns) and white kura (traditional storehouses) are crammed together at Arima Onsen, the ancient hot water spa nearby Kobe. The Arimagawa river winds itself along the edge of the village.

The white bridge crossing the Arimagawa is Taikobashi (太古橋). It connects the village with the Sanda Kaido (三田街道), the highway that lead to nearby Sanda. The large mountain in the back is Mount Rokko, still largely without trees at this time. In 1902 (Meiji 35) massive tree planting programs were started. In 1903 (Meiji 36), for example, some 730,000 trees were planted in the Futatabisan (再度山) area.1

According to legend, two gods observed three injured crows drinking water from a pool at Arima. Several days later they noticed that the crows’ injuries were healing, and Arima’s history as a recuperating spa was launched.

The little spa is mentioned in Japan’s second oldest history book, the Nihon Shoki. According to these chronicles, Emperor Jomei (593–641) spent 86 days bathing in Arima in 631, while Emperor Koutoku (596-654) spent 82 days in 647. Quite a difference from the hurried one night-two day visits of modern tourists.

After this auspicious start, Arima disappears from the records for a while. But it reappears in the 8th century. Another legend tells us how the monk Gyoki (行基, 668-749), a historical person who did much to help the poor, came to build the buddhist temple Onsenji (also known as Yakushi temple).

One day, Gyoki met a sick person on his way to Arima. He told Gyoki that he had no money for food and that his weak body could only stomach fresh fish. So Gyoki went to Nagasu (in Amagasaki) and came back with a load of fresh fish.

After he had eaten, the man complained about terrible pain he felt in his skin. “Please lick my skin with your mercy,” he pleaded. When Gyoki did so, a great light emanated from the sick man and the image of Yakushi Nyorai, the Medicine Buddha, appeared before Gyoki.

“I am the Medicine Buddha,” he said. “Your compassionate heart has greatly moved me. Go now to Arima and help the sick. I will assist you in your work.”2

Gyoki went to Arima and did what he was told. To celebrate Yakushi Nyorai, he built Onsenji. The story may be a legend, but Gyoki did rebuild Arima and built a temple that survives to this day. It has statues of both Gyoki and Yakushi Nyorai.

In 1097, much of Arima was destroyed by a flood and for almost a century it did not function as a spa. Around 1191, the monk Ninsai (仁西) had a dream that he should rebuild Arima. He restored the spa, repaired Onsenji and started to run twelve inns for priests called bo (坊). This was right after the Taira clan had lost the Genpei War from the Minamoto.

Survivors of the Taira clan had come with Ninsai from Yoshino in Nara, where he had been head priest of Kougenji (光源寺). These Taira survivors started to manage the inns. More than eight centuries later, there are still many onsen ryokan that carry the character 坊 in their name.

Fate was kind to Arima until the 16th century. In 1528, Arima was destroyed by fire. Shortly thereafter, in 1545, it was sacked by an invading army. In 1576, it was once again destroyed by fire. This time, the village was not saved by a religious monk, but by a ferocious warrior. Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536?-1598), one of the three generals who strived to unify Japan, visited Arima in 1583 to heal his exhausted body and mind. He soon began to visit Arima regularly and in 1597 started a vast reconstruction program for the spa. At this time, twelve additional bo were added to the twelve founded by Ninsai.

During the Edo Period (1603-1868), Arima started to gain fame as a spa resort. This was a prolonged time of peace, and although travel was greatly restricted, people were allowed to travel for religious or health reasons.

In those days, inns didn’t have their own baths and visitors shared a public bath of about 3 by 6 meters. As the number of visitors increased, the bo launched small inns called koyado.3

Arima’s prosperity continued during the Meiji Period. Its close location to Kobe made it very popular with foreign visitors. One of the first, if not the first, travel guides to mention Arima was Keeling’s Guide to Japan, published in 18904:

The hot spring at Arima, about ten miles in the interior are said to cure all diseases (i.e. of the cutaneous and rheumatic type). Here also can be found the celebrated Arima straw ware, which is so eagerly sought after by the purchaser of the cheaper line of curious.

Every guide after that mentioned the little hot spring village.

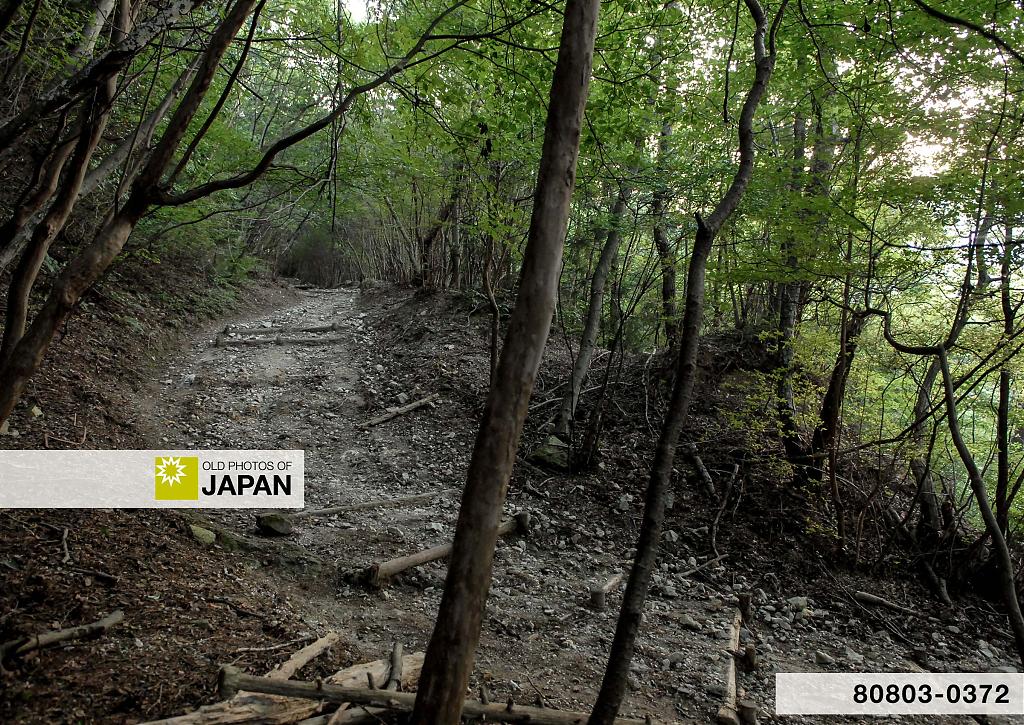

Arima’s location in the mountains made it a bit difficult to reach. Initially, visitors walked or were taken there by kago (sedan chair). Later they’d take Jinrikisha (rickshaw), a cheap and fast way to travel during the Meiji Period.

Traditionally, the village was reached by one of four main road connections:

- Sumiyoshi Kaido was a 12 km route from Sumiyoshi over Mount Rokko, which took about four hours. Because it was a shortcut, it was used to transport fish from Nada. It therefore became known as Totoya Michi (魚屋道, fishermen’s road). The road still exists and is today a popular hiking trail, starting at Hanshin Fukae Station.

- Sanda Kaido connected Arima with the rice producing area of Sanda. The road survives today as Route 51.

- Kobe Kaido lead from what is now Hyogo-ku, via Karato (唐櫃), to Arima.

- Namaze Kaido was the entry way for people coming from Kyoto and Osaka. It lead through Ikeda, Kawanishi and Takarazuka, and shared part of its way with the Sumiyoshi Kaido.

Modern transportation took some time to reach Arima. In 1898 (Meiji 31), a train connection now known as the JR Fukuchiyama Line was opened and allowed visitors to Arima to take the train to Namaze Station, from where they continued by Jinrikisha.

The very first bus connection to Arima was only started up in 1905 (Meiji 38). It connected Arima with Sanda Station, where people transferred to the current JR Fukuchiyama Line.

In 1915 (Taisho 4), a rail connection was opened between Arima and Sanda, and on November 28, 1928 (Showa 3) Arima was finally connected directly to Kobe when a railway between Minatogawa Station and Arima Onsen Station was inaugurated. The trip took 57 minutes.5

As the village became easier to reach, business increased and the population surged. It reached its peak in 1965, when there were some 3,968 inhabitants. It has gone down ever since.

Population67

| 1872 (Meiji 5) | 1,341 |

|---|---|

| 1916 (Taisho 5) | 1,770 |

| 1936 (Showa 11) | 2,007 |

| 1965 (Showa 40) | 3,968 |

| 1992 (Heisei 4) | 2,636 |

| 2014 (Heisei 26) | 1,485 |

The town is now, like most Japanese spa resorts, an ugly concrete jungle—even the rivers are lined with concrete. But it is still a fun place to visit. The narrow roads offer lots of surprises and tiny pockets of traditional Arima survive. The baths are of course its main attraction.

In April 2008, a new onsen ryokan called Gosho Bessho (御所別墅) was started that offers hope for the return of beauty to the village. Instead of a non-descript concrete building, it is a wooden structure that fuses modern and traditional Japanese design. It is actually owned by the same family that have run Goshobo (see #3 on the numbered image on top, and the image below) for many centuries.

Notes

1 (1989). A Centennial Tribute of Kobe. City of Kobe, 21.

2 Motoyu Ryuusenkaku (元湯龍泉閣). Folklores in Arima. Retrieved on 2008-08-04.

3 有馬温泉観光協会。有馬の歴史。 Retrieved on 2008-08-04.

4 Farsari, A. (1890). Keeling’s Guide to Japan. A. Farsari, 136.

5 鷹取嘉久(1996)。見て聞いて歩く有馬。鷹取嘉久。

6 ibid

7 Wikipedia, 有馬町. Retrieved on 2021-08-22.

Published

Updated

Reader Supported

Old Photos of Japan aims to be your personal museum for Japan's visual heritage and to bring the experiences of everyday life in old Japan to you.

To enhance our understanding of Japanese culture and society I track down, acquire, archive, and research images of everyday life, and give them context.

I share what I have found for free on this site, without ads or selling your data.

Your support helps me to continue doing so, and ensures that this exceptional visual heritage will not be lost and forgotten.

Thank you,

Kjeld Duits

Reference for Citations

Duits, Kjeld (). Arima 1890s: Hot Spring Village, OLD PHOTOS of JAPAN. Retrieved on January 1, 2026 (GMT) from https://www.oldphotosjapan.com/photos/303/arima-hot-spring

Tornadoes28

The difference between the old photo and the modern one is amazing. It is also sad to see how the old village was lost to the ugly modern buildings.

#000200 ·

Kjeld Duits (Author)

Hi Tornadoes28,

I felt the same way about this image. Surprisingly, when I showed the old image to people in Arima—both villagers and visitors—, every single person said the same thing, “ah, it is so similar.” I was shocked. When I probed deeper, they all admitted preferring the older image, though. I think it was mostly the shape of the mountains and the general lay-out that made them make this comment.

I guess that people in Japan are so used to their landscapes having been so completely reworked during the past 50-100 years, that to them these images still look alike…

#000238 ·